CAIRO, Egypt — With the backing of both liberals and conservative “Salafist” Muslims, an unlikely front-runner has emerged in Egypt’s crucial presidential race.

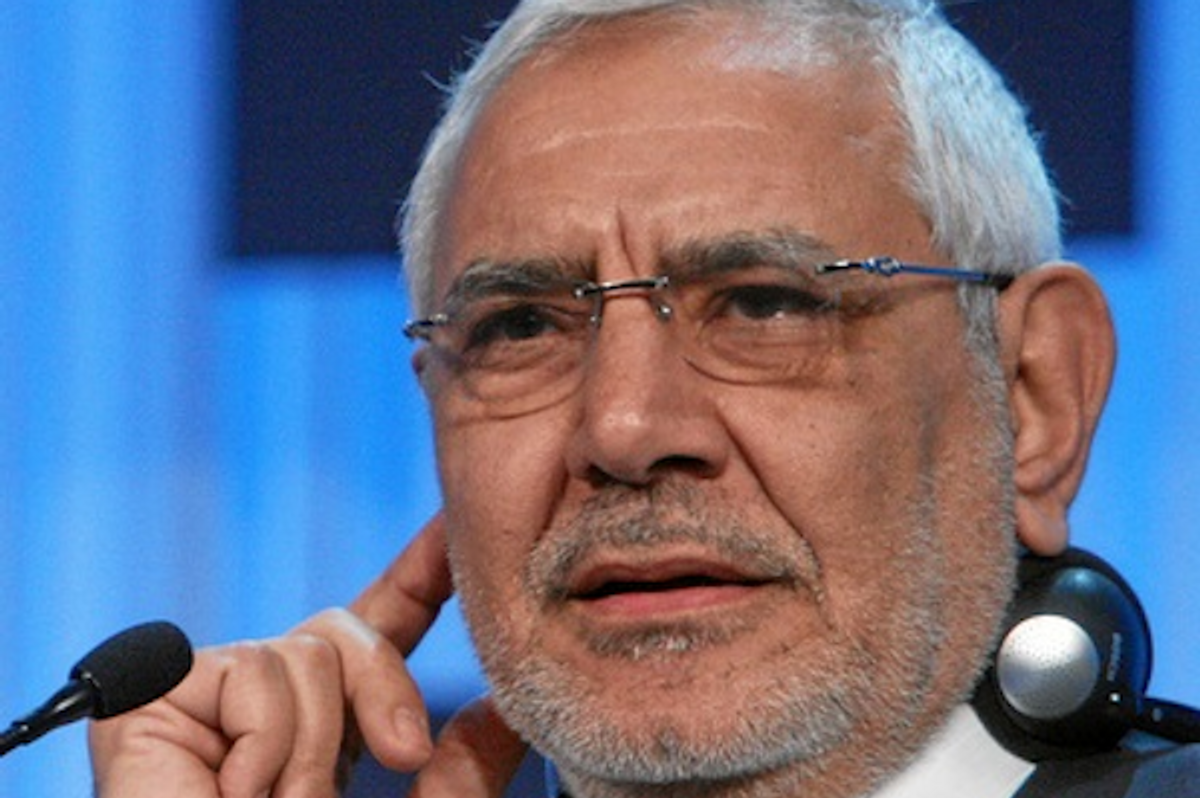

The candidate is former Muslim Brotherhood member and moderate Islamist Abdel Meneim Aboul Fotouh. In the past week, he has clinched endorsements from across the political spectrum, including from three key Islamist groups. Fotouh suspended his campaign this week after clashes erupted between protesters and plainclothed assailants, but is expected to resume before elections are held on May 24.

The candidate is former Muslim Brotherhood member and moderate Islamist Abdel Meneim Aboul Fotouh. In the past week, he has clinched endorsements from across the political spectrum, including from three key Islamist groups. Fotouh suspended his campaign this week after clashes erupted between protesters and plainclothed assailants, but is expected to resume before elections are held on May 24.

His status as a prominent Brotherhood outsider seems to be one of his main selling points — both for other Islamists eager to break free from the influence of the 80-year-old Brotherhood movement, and for liberals scared of its rise.

The Brotherhood’s own Islam-oriented Freedom and Justice Party (FJP) won a sweeping victory in the country’s recent parliamentary elections and now dominates parliament. Critics worried that if they took the presidency as well, the Brotherhood’s power would be too great in Egypt’s post-revolution political landscape, with uncertain consequences for the country’s nascent democracy.

“It’s unacceptable to have both a Muslim Brotherhood majority in parliament and a Muslim Brotherhood president when the government should represent everyone,” said Essam Shebl, vice chairman of the moderate Islamist party Al Wasat, which endorsed Fotouh on Monday.

“[Fotouh] has an Islamist background, but is calling for moderate Islamic governance,” Shebl added. “This is what is best for the country, and I think the Salafi [more conservative Islamists] in general are starting to see the benefits of the moderate approach championed by Dr. Aboul Fotouh, and I see that was great progress.”

The Brotherhood’s own presidential candidate, Mohamed Morsi, is polling strikingly low — last, in some cases — according to surveys released by the government-linked Al Ahram Center for Political and Strategic Studies.

Thirteen candidates will face off in the presidential elections on May 24, with a run-off between the top two slated for June 16. The Brotherhood had initially promised not to field a candidate for the presidential elections, but later back-tracked, causing many Egyptians to view their intentions with suspicion.

Fotouh, once a member of the Brotherhood's Supreme Guidance Council, was suspended by the movement in May 2011 when he announced his intention to make a bid for the presidency. The Brotherhood and its party refused to support him.

But since then, he has built a swell of ground-level support by campaigning for the right to education and healthcare for all Egyptians, ending all military trials for civilians and boosting foreign tourism to save the ailing economy.

In contrast to some of the other Egyptian Islamists, Fotouh is against imposing Islamic law on non-Muslims. The rise of Islamic parties, which collectively hold roughly 70 percent of seats in parliament, have worried liberals and the Coptic Christian minority here.

Many said that without the support of the Brotherhood, Fotouh stood no chance of becoming Egypt’s next president. But several local think-tanks and newspaper polls have him either leading the race or in second place after former foreign minister and secular-liberal candidate, Amr Moussa.

On Tuesday, the secular Egyptian Google executive, Wael Ghonim — who became famous and galvanized protests during last year’s revolution when he wept during a live television interview — endorsed Fotouh for president on Twitter.

In addition to the moderate Al Wasat Party, the ultra-conservative Al Nour party and the former militant organization Al Gama’a Al Islamiya, which together encompass a wide swathe of the Islamist vote, endorsed Fotouh over the past several days.

But as fundamentalists, these parties may be less than interested in advocating Fotouh’s more measured interpretation of Islamic law than outflanking the Brotherhood’s seemingly invincible FJP.

Al Nour, of the Salafist strain of Islamist movements, which emphasizes practicing Islam in the manner of the Prophet Mohammed’s immediate followers in 7th- and 8th-century Arabia, holds 20 percent of the seats in parliament.

“The Muslim Brotherhood is dominating the political scene to a dangerous extent,” said Sameh Abd Al Hamid, a member of the Al Nour party’s central elections committee in Alexandria.

He used the Freedom and Justice Party’s creation last month of a 100-member constitution-writing committee composed of 25 of their own parliamentarians as an example of their attempt to eclipse other political forces.

According to a poll by the Al Ahram Center for Political and Strategic Studies, 45 percent of Egyptians who voted for the party in the parliamentary elections said they would not do so again.

They have presided over a largely toothless parliament still subject to the will of Egypt’s military rulers, the Supreme Council of Armed Forces.

“Fotouh won’t be controlled by the Brotherhood because of his long-standing differences with them,” Hamid said.

But there are concerns the support of Al Nour and Gama’a Islamiya will pressure Fotouh to compromise on his more tempered Islamist principles — forcing him to concede to the more extreme elements in power.

Al Nour’s Hamid admitted that Fotouh held views at odds with their own “more pure” interpretation of Islamic texts.

“We do feel that Aboul Fotouh has an overly lenient [Islamist] ideology,” Hamid said, adding that the party wanted to end the “corrupt practices” of some foreign tourists and promote educational and medical tourism to Egypt.

“To be honest, we wanted a better Islamic candidate with a more pure interpretation of Islam,” he said. “But he is the best of all the Islamist candidates, and politics pushes you to make concessions.”

For their part, the Brotherhood is trying to thwart criticism as it seeks to control post-revolution politics.

Ahmed Al Nahhas, a Muslim Brotherhood activist and member of the Freedom and Justice Party’s Supreme Committee in Alexandria, says if they in fact lose the presidential race, there will be some political soul-searching to do.

“The Muslim Brotherhood [as a social organization] will not be affected,” he said. “But the [Freedom and Justice] party will be definitely lose some of its popularity.”

Heba Habib contributed reporting from Cairo, Egypt.

Shares