There was good reason for Republicans to cry foul over the Obama campaign’s advertisement highlighting the president’s killing of Osama bin Laden; the GOP has lost its decades-long edge on national security. According to a Washington Post poll, “By a margin of more than 2 to 1, Americans say the president’s handling of terrorism is a major reason to support rather than oppose his bid for reelection.”

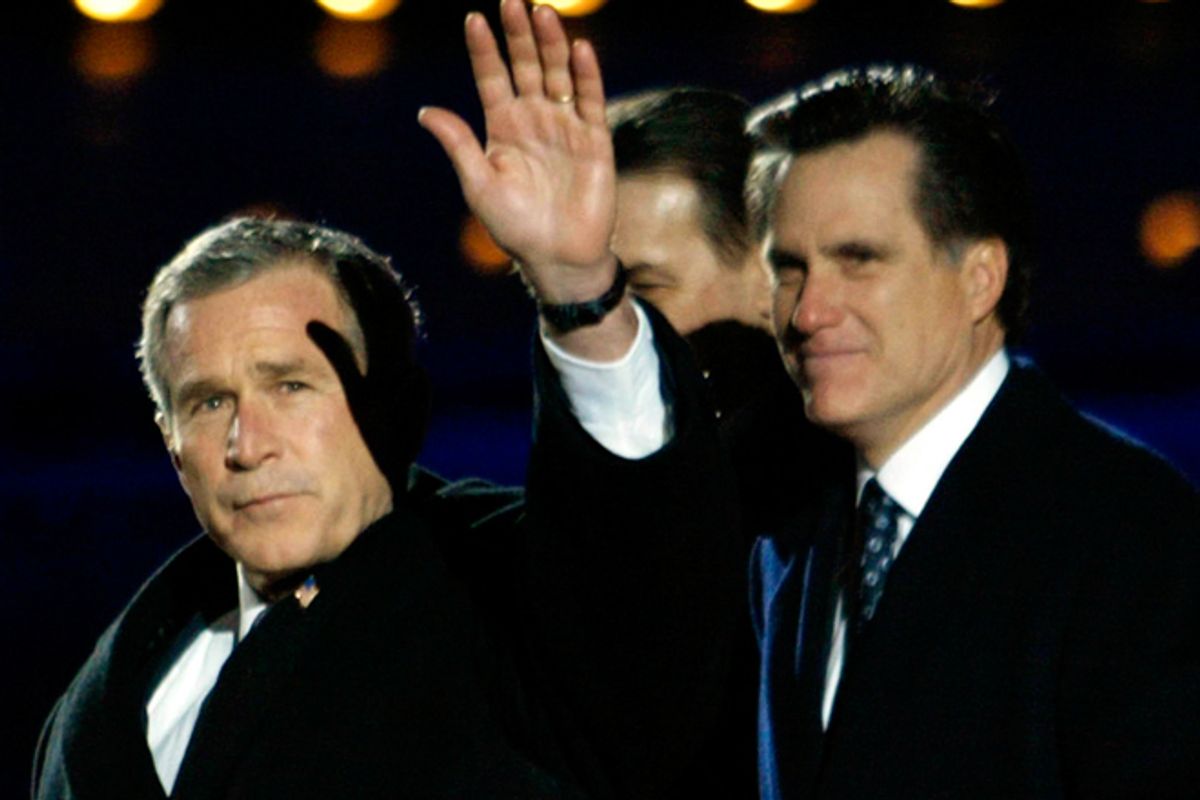

Republicans lost their popularity on security issues for one reason: George W. Bush’s foreign policy was a disaster. And yet, the party’s nominee, Mitt Romney, has assembled a foreign-policy team composed almost exclusively of individuals with the same war-always mentality and ideology that served Bush — and the United States — so poorly. In some cases, the exact same men responsible for Bush’s catastrophic national security policies are advising Romney. The former Massachusetts governor could have included some of the pragmatists and realists from the George H.W. Bush administration. Instead, a Romney presidency seems like it would be Bush 43 all over again.

Richard Grenell, who served as United Nations spokesman under Bush, may be gone from the Romney campaign after an uproar over his sexuality, but there are plenty more former Bushies. First off, there are Romney’s “special advisors.” There’s Michael Chertoff, W.’s Homeland Security director. Chertoff oversaw DHS’s failures during Hurricane Katrina, and amassed unprecedented powers of secrecy. Next up is Eliot Cohen, counselor to the State Department for Bush’s last two years and on the Defense Policy Advisory Board for the president’s entire term. Cohen was an adamant supporter of the Iraq War and advised Bush directly on the issue. Or take Cofer Black, the man who infamously said to Bush in September 2011 about al-Qaida that "When we're through with them they will have flies walking across their eyeballs.” Black went on to become chairman of Blackwater, where he resigned after the company illegally bribed Iraqi officials.

Then there are the 13 “working groups” composed of equally worrisome individuals. The Middle East and North Africa Working Group is co-chaired by Bush’s Assistant Secretary of Defense Mary Beth Long, and Meghan O’Sullivan, Bush’s special assistant and deputy national security advisor for Iraq and Afghanistan. The remaining co-chair is Walid Phares, who never worked for Bush but advised Lebanese warlords in the 1980s. Romney has reportedly promised Phares a top job in his administration, despite his virulently anti-Islamic views.

All told, Romney lists 37 holdovers from the George W. Bush administration -- the very same administration he and all other Republican candidates barely referenced during their many debates because it was so discredited and toxic, even to the Republican base.

It didn’t have to be this way. There are, in fact, people in Republican circles who are sensible on international affairs. The Cato Institute, in particular, has experts that could dramatically change the direction of American foreign policy. Men like Justin Logan and Christopher Preble were prescient on Iraq and a host of other issues. Similarly, the Center for the National Interest (formerly the Nixon Center) has a host of solid scholars, including ones like Dimitri Simes and Geoffrey Kemp, who have valuable government experience in the Nixon and Reagan administrations, respectively, and a history of perceptive analysis. Richard Haass, president of the Council on Foreign Relations, would have been another good pick.

So why aren’t guys like this being tapped? Why is the GOP sticking with a discredited foreign-policy approach rather that looking to its own past for wiser counsel? “Most of the realists and pragmatists have simply been driven out of the Republican Party,” says Stephen Walt, who writes a blog at Foreign Policy and teaches at Harvard. “The neoconservatives have been driving the agenda since Bush was elected and they remain well-entrenched.”

Another factor is that the Republican Party’s base remains strongly militaristic and reluctant to recognize limits on American power. Jon Huntsman’s failed presidential campaign illustrated that problem. The good news is that nobody seems to be calling for nation-building and occupying foreign countries in the mold of Iraq and Afghanistan. But that’s the only lesson that seems to have been learned from the last decade of foreign-policy debacles.

Finally, it may just be that the United States has too much power to change course. While the Unites States has undoubtedly made disastrous decisions in the last decades, it is so powerful that it is largely insulated from the consequences of them. If Romney’s foreign-policy advisor list is anything to go by, a Romney administration would have to teach the U.S. all over again about the problems with trying to police the world. Prepare for Bush redux.

Shares