On a weekday evening, at a renovated West Philadelphia church, a wide array of community members discussed the state-appointed School Reform Commission's (SRC) recently-announced plan to privatize most of the Philadelphia School District -- labeled by SRC head Thomas Knudsen as "decentralization.”

The meeting came on May 8th, just two weeks after the SRC announced their radical proposal. A woman in her mid-thirties, voice quivering slightly, admitted: “We knew that what happened in Wisconsin last year would happen here too. This is going to be a huge fight.”

The agenda of this meeting of public school teachers, students, labor organizers and seasoned activists (including members of Occupy Philadelphia) included crafting a response to what some here see as the “Shock Doctrine” being applied to Philadelphia public education. Residents have received an ultimatum from the city: accept property tax hikes – which Mayor Michael Nutter says would raise upwards of $92 million, but would disproportionately affect low income residents -- or let schools close.

“In a way, politicians and business interests co-opted the idea of decentralization,” said one activist. “It should be about giving power to communities to determine what they need.”

Not in the way the SRC and others have framed it, however.

Ron Whitehorne, a former teacher and Philadelphia Federation of Teachers (PFT) member, says that there is no confidence in the SRC's plan among many school union members.

The SRC's plan, in essence, is to “decentralize” the school district and allow for-profit interests to turn public schools into charters.

“There is no proof that privatization is better,” adds Amanda, a Students for a Democratic Society organizer [who asked that her last name not be used]. “All the articles which have come out on this issue since this plan was announced point out this fact.”

She has a point – public officials themselves have said recently that charter schools do not always produce better results compared to public schools, although there are charters which do perform well. High performance Charters are definitely in the minority, however.

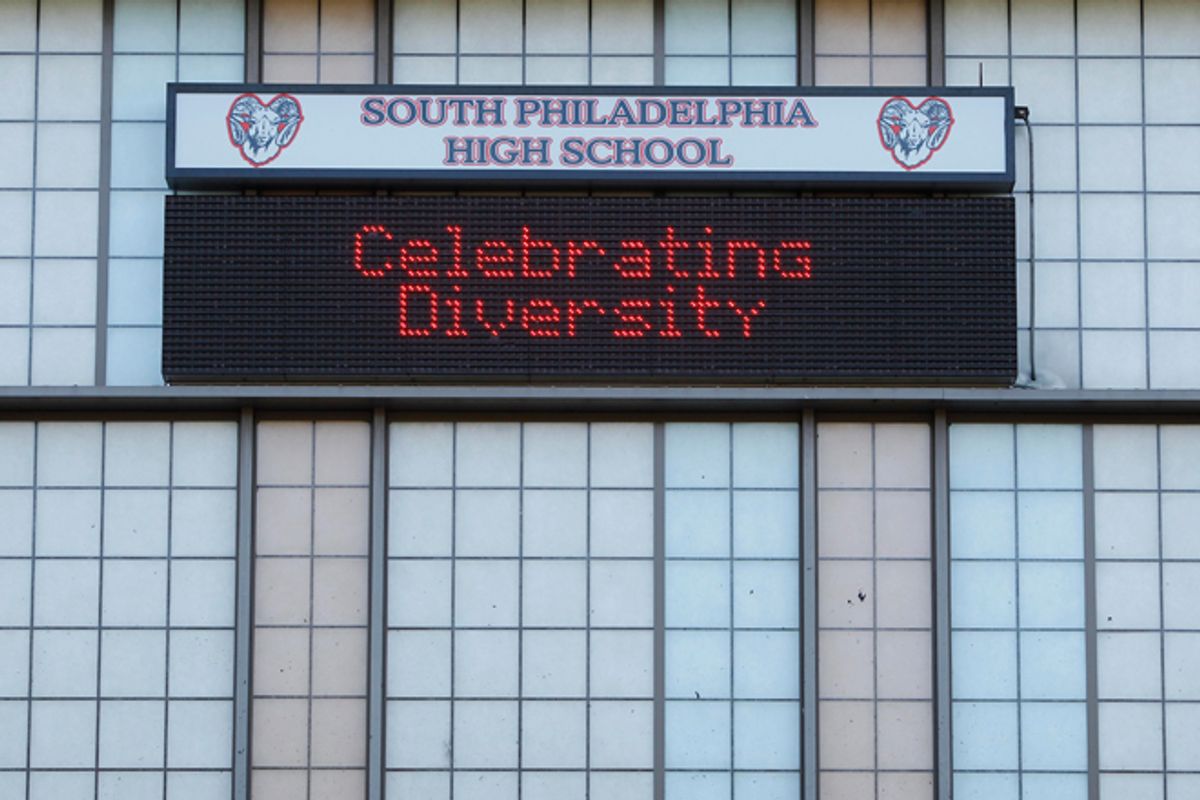

“I'm deeply concerned that corporations want to turn our schools into cash cows,” said Cynthia Murray Holmes, a South Philadelphia elementary school teacher. “They've succeeded so far in pitting their model against public schools – which is not what charter schools were created for. And I don't think putting our children's education in the hands of for-profit interests is wise.”

She adds that charters were supposed to be testing grounds, in essence, to come up with new ideas to improve public education. The concept was never intended to be used as a tool to privatize entire school districts, and certainly not to the extreme that officials are steering towards. Many here feel that the political leadership are taking privatization as an easy – and by no means correct - solution to the education funding crisis. They point to ending tax abatements given to corporations, for instance, as something that could stave off this privatization effort.

It is apparent that city officials who support a draconian privatization plan, as well as their wealthy benefactors, created such a small window for public reaction on purpose. And according to many assembled at the church, the power players' disdain for democracy is topped off with Mayor Nutter's request to the people of Philadelphia: “Grow up and deal with it.”

“The resonant theme here,” says Whitehorne to the assembled crowd, “is democracy. The citizens have no real say in this. This [SRC] was not elected, and that's unacceptable.”

And judging by these concerned people, they think this plan is unacceptable too.

Shares