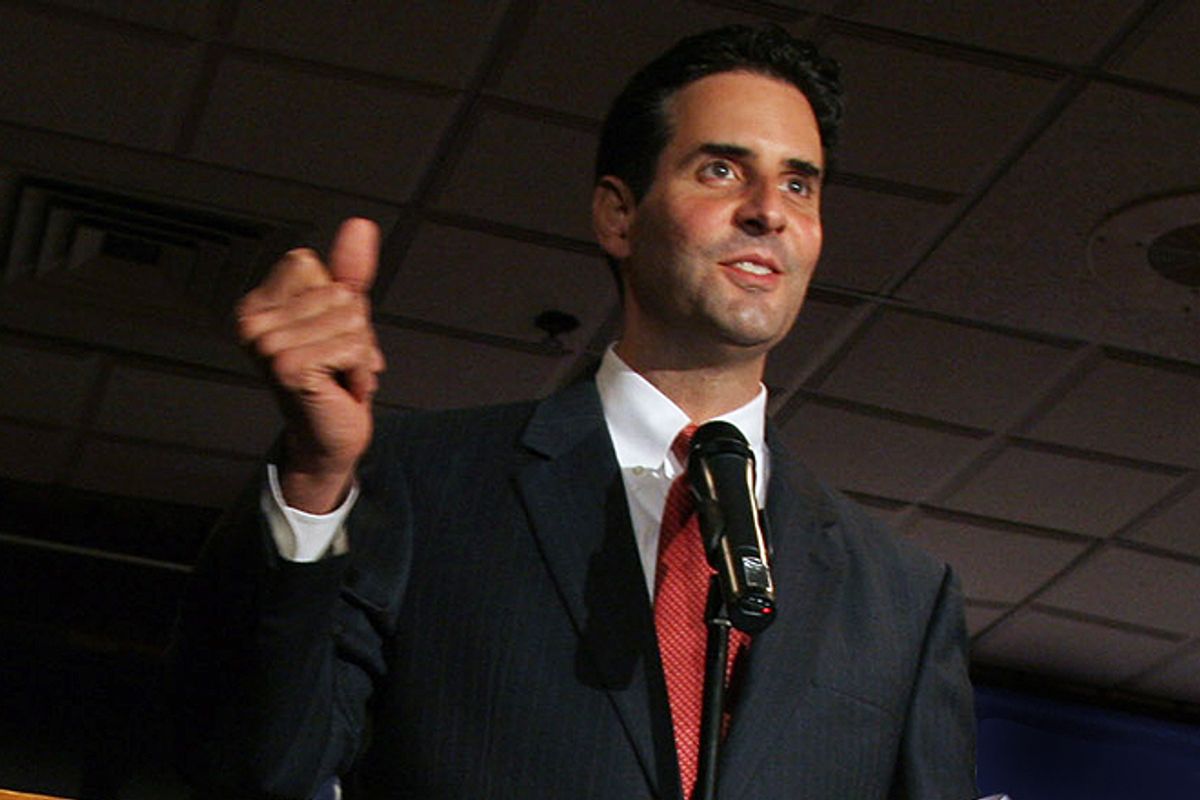

Maryland congressman John Sarbanes, D-3rd, isn’t in a highly contested race this year — his opponent is Constitution Party candidate and bartender Eric Knowles. So he has decided to conduct an experiment. Could a congressional candidate in 2012 fund his campaign largely with contributions from small donors? And could he build a network of donors that could be mobilized at a moment’s notice, to pony up cash and fend off attacks by a super PAC?

In October, Sarbanes launched the Grassroots Donor project, a model of fundraising that mimics the Fair Elections Now Act, legislation proposed in 2011 that would give congressional candidates who assemble a large number of small donors access to a federally funded matching fund. The Fair Elections Now Act stands almost no chance of becoming law, and with the Bipartisan Campaign Reform Act made moot by the Supreme Court’s ruling in the Citizens United case, Sarbanes and his colleagues are increasingly frustrated.

Sarbanes’ Grassroots Donor effort is reminiscent of candidate Obama’s 2008 “army of small donors,” which accounted for more than $100 million in contributions. Sarbanes says, yes, “that financing approach Howard Dean pioneered and President Obama perfected serves as a model. But the success of that has only really been proven at the level of presidential campaigns or nationalized races. At the level of rank-and-file congressional races it’s still largely untested.” It’s also arguably most critical at the congressional level because that’s where candidates have the greatest vulnerability to super PAC and other big money attacks.

For example, late last month Karl Rove’s super PAC, Crossroads GPS, paid for television advertising targeting Nevada’s Democratic Senate candidate, Shelley Berkley. Crossroads spent $1.2 million on a package of ads airing in states with competitive races, including Montana, Missouri, Nevada, North Dakota and Virginia. In response, Berkley sent a flurry of emails to supporters asking them to donate $5 or $10 to fight back. (Berkley’s campaign didn’t answer requests from Salon for the amount raised from those small donors.)

After Sarbanes raised $500,000 from traditional donors (individuals giving more than $100, up to the federal limit of $2,500) he locked the money away where it will remain inaccessible until he gets 1,000 people to give between $5 and $100 to his campaign. At this stage it’s less about the money raised from 1,000 donors and more about the number of people involved. “The premise is that if you can get a thousand people to contribute at the grass-roots level, you would have learned enough techniques for reaching them that you can get the next thousand and the next thousand,” says Sarbanes. “The goal of the first thousand is to break into a new way of raising funds, and then you keep going back. Over time the number of donors is large enough to help you fight back.” The congressman is looking for a proof-of-concept, to show his colleagues in the House that it’s possible to build a network of small donors, most of them your constituents, and wean yourself off PAC and other special interest money.

“The collective effect of our dependency on that money is seen when we go to make public policy. The institution leans more in the direction of special interests than in the direction of the public,” he says. For example, even though the public wants the tax on earnings from hedge funds increased, Congress hasn’t been able to do it because the financial industry has so much influence, says Sarbanes. He hasn’t taken any corporate or labor PAC money this election cycle, but acknowledges that most of his colleagues don’t have that luxury.

“Other members are interested in this, but if they are in a competitive district, they have to deal with the system the way it is. I can’t pass judgment on that, a lot of my colleagues are in very difficult races,” he says. “I have some breathing room, so I have the opportunity to experiment, and I feel a responsibility to do this.”

But it’s proving tougher to do than he thought. Sarbanes has 400 small donors so far, three-quarters from Maryland. The average donation is $30. Yet it could work -- even if members limit their grass-roots network to donors from their respective districts, that’s about 710,000 people according to the U.S. Census, thousands of them with the ability to give $5, $10 or $15.

Sarbanes’ Maryland district is largely white, with about 15 percent African-American, 8 percent Hispanic and 6 percent Asian. It’s considered a relatively affluent district, although incomes run the gamut. Sarbanes’ issues are the environment — specifically protecting the Chesapeake Bay — as well as environmental education. He’s also involved with public service and volunteerism, and sponsored the Public Service Loan Forgiveness Act, which allows college students with significant federal debt to have that debt forgiven if they perform 10 years of full-time public service work. He authored legislation that established VetCorps, a program within AmeriCorps that provides service opportunities to veterans and military families. And he’s worked to address shortages of healthcare professionals in the workplace.

If Sarbanes can’t reach his 1,000-donor goal, he’ll look into other ways to build a small donor network and tweak his model accordingly. His goal is to introduce campaign finance reform legislation that might include things like a tax credit for the first $50 of contributions to a congressional candidate. “Or a matching fund,” says Sarbanes, possibly funded by a tax on super PAC donations.

“I just want to see if this is possible, to raise money in a different way,” he says. Right now, says Sarbanes, a House member’s downtime is spent making calls to big donors or asking for money from PACs and industry groups. Instead, Sarbanes wants to figure out how to recruit grass-roots donors and what resonates with them. “The way money has to be raised now, it’s consuming us,” says Sarbanes. “It’s making it impossible for us to do the job we want to do.”

Shares