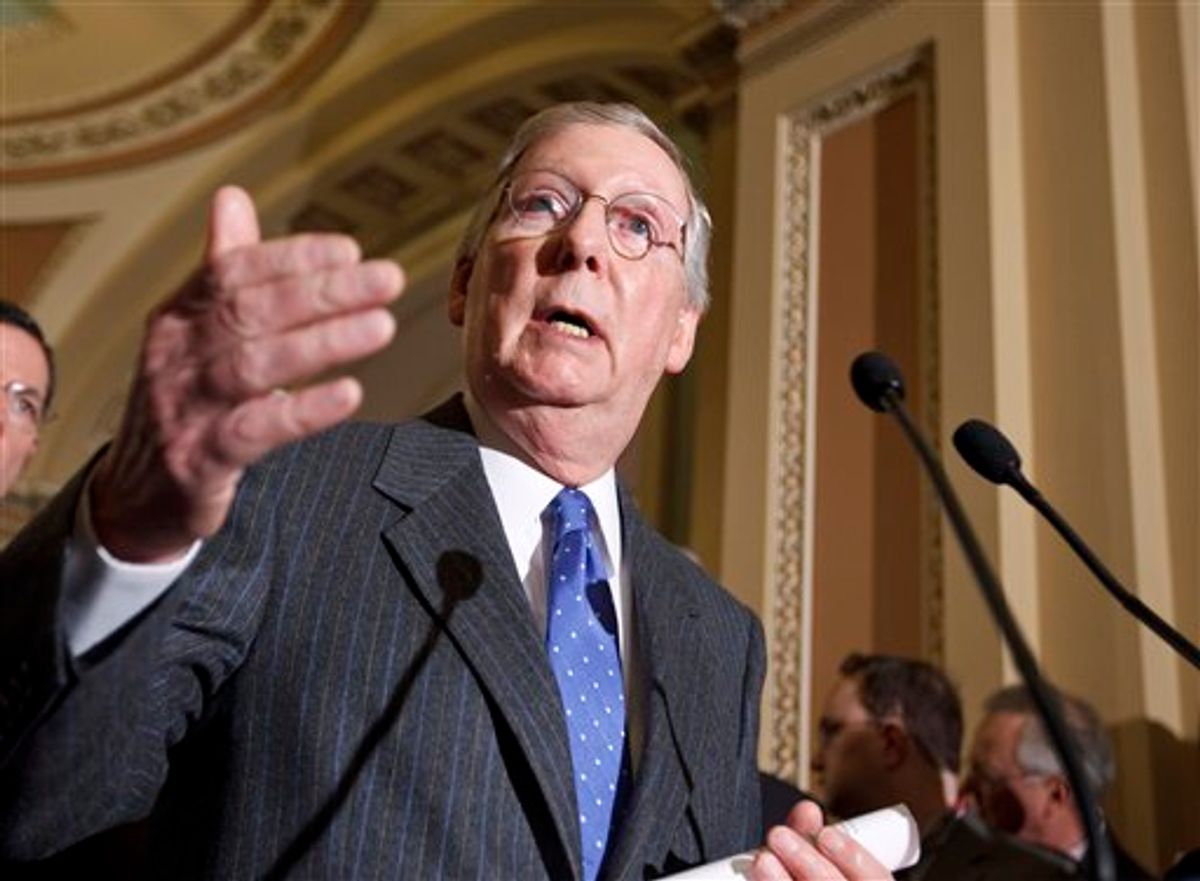

The possibility that Mitch McConnell might be ousted when Senate Republicans pick their leader after the November elections was raised by a Sunday New York Times story, which found several Tea Party-aligned GOP candidates refusing to commit to backing him. McConnell, though, still has plenty of allies and remains the prohibitive favorite to retain his post.

But there’s a more interesting question at work here than whether he can hang on: Why would he even want to?

The impetus for the Times piece was the landslide victory of Richard Mourdock over Richard Lugar in an Indiana Republican primary last week, which refocused attention on the rising influence of Tea Party-style conservatism in the upper chamber. Mourdock, if he’s elected, will join a bloc of Republican senators whose governing approach mirrors that of South Carolina’s Jim DeMint, the Tea Party’s de facto leader on Capitol Hill.

To promote unity within his ranks and to secure his grip on power, it’s important for McConnell to respond to his party’s evolution toward the DeMint/Tea Party style, something he’s been doing lately. The problem, though, is that this style severely constrains his ability to exercise the traditional prerogatives of a Senate leader and threatens to render him the upper chamber’s equivalent of John Boehner, who lives with the knowledge that any deal-making with the other side could spur an intraparty coup.

This reflects an important point about Tea Party Republicanism: It isn’t really about ideology; it’s about governing tactics.

After all, the battle for the Republican Party’s ideological soul was fought and settled decades ago. In the late 1970s, a movement somewhat similar to the Tea Party gave rise to a number of primary challenges to sitting GOP senators. The targeted incumbents, though, were genuine liberals – New Jersey’s Clifford Case, Ed Brooke of Massachusetts, and New York’s Jacob Javits. The Republican Party of that era was in the midst of a sweeping geographic and demographic evolution, one that established it as the home for white Southerners and newly mobilized evangelical Christians and left the old Rockefeller wing extinct. When Ronald Reagan triumphed in 1980, it certified the GOP as the conservative party it remains today.

The primary challenges of the current Tea Party era are not defined by similarly vast ideological gulfs. Lugar, for instance, was generally a party man in his Senate votes, racking up a fairly conservative record and voting against President Obama’s major domestic initiatives. But he did leave some room for independence and compromise, particularly in his specialty area of foreign policy. His opponent, Mourdock, was to Lugar’s right on some issues, but what really distinguished him is his belief that the Senate is a venue for partisan warfare.

“Bipartisanship,” Mourdock declared last week, “ought to consist of Democrats coming to the Republican point of view.”

This is as concise a distillation of the Tea Party’s governing vision as you’ll find. It’s not really about moving the GOP to the right; the party is already there, and has been for a while. It’s about reflexively opposing the other party on every issue, resisting compromise at all costs, and exploiting every available legislative tool to stymie the other side. This mind-set is already pervasive in the House, and as the Times story shows, it’s now making its way into the Senate.

The lesson that Lugar’s defeat sends to individual Republican senators is that they risk the same fate if they don’t get with the Tea Party program. Traditionally, there’s been room for them to carve out a specialty area – like Lugar with foreign policy – and to reach across the aisle to advance legislation that affects it. But that model is fast giving way to the Tea Party’s expectation of relentless, 24/7/365 partisan warfare.

A case study in how this works can be found in Orrin Hatch, who was spooked when his Utah colleague Bob Bennett was denied renomination in 2010. Hatch’s voting record is reliably conservative, but he has (or had) a reputation as a deal-maker. When Bennett went down, though, Hatch swore off compromise and recast himself as a Tea Party-friendly partisan warrior. It will probably be enough to save his job, which only reinforces the message of Lugar’s defeat.

All of this affects what McConnell is, and isn’t, able to do as the GOP’s leader. In the past two years, he’s played a crucial role in resolving standoffs with the White House that House Republicans instigated – over the debt ceiling last summer and expiring payroll taxes before Christmas. But his ability to keep doing this depends on having space to negotiate and cut deals with Democrats, and with every Tea Party primary triumph, that space erodes a little more.

The Senate is not the House yet, but the Tea Party is pushing it in that direction. As Norm Ornstein and Thomas Mann explain in their new book, the principles of a parliamentary system – absolute party loyalty and reflexive, unyielding opposition from the out-of-power party – are coming to define Capitol Hill. For McConnell, this will force a personal reckoning over whether he’s comfortable functioning as the kind of leader such a system demands. For the rest of the country, it will force a different kind of reckoning, as the total incompatibility of the parliamentary style with the American system becomes apparent.

Shares