Kelley Williams-Bolar is giving a speech in the dark. The Ohio mom is rattling off the standard remarks she’s delivered in public appearances since being catapulted onto the national stage last year. It’s an unseasonably warm day and the lights in the room are off, her face lit only by the glow of the computer screen in her father’s home. The address on the door outside is the one she used on her now-famous falsified documents—the ones that landed her in jail for nine days for illegally enrolling her daughters in a neighboring public school district.

“First, I talk about how I received my indictments, and then I give the laundry list of stipulations for my probation,” says Williams-Bolar, who is halfway through her two-year sentence. The 42-year-old single mother, with an otherwise spotless criminal record, is not allowed to drink, must submit to drug tests and reports monthly to a probation officer. She had to perform 80 hours of community service and pay $800 in restitution, as well as the cost of Summit County’s prosecution against her.

“First, I talk about how I received my indictments, and then I give the laundry list of stipulations for my probation,” says Williams-Bolar, who is halfway through her two-year sentence. The 42-year-old single mother, with an otherwise spotless criminal record, is not allowed to drink, must submit to drug tests and reports monthly to a probation officer. She had to perform 80 hours of community service and pay $800 in restitution, as well as the cost of Summit County’s prosecution against her.

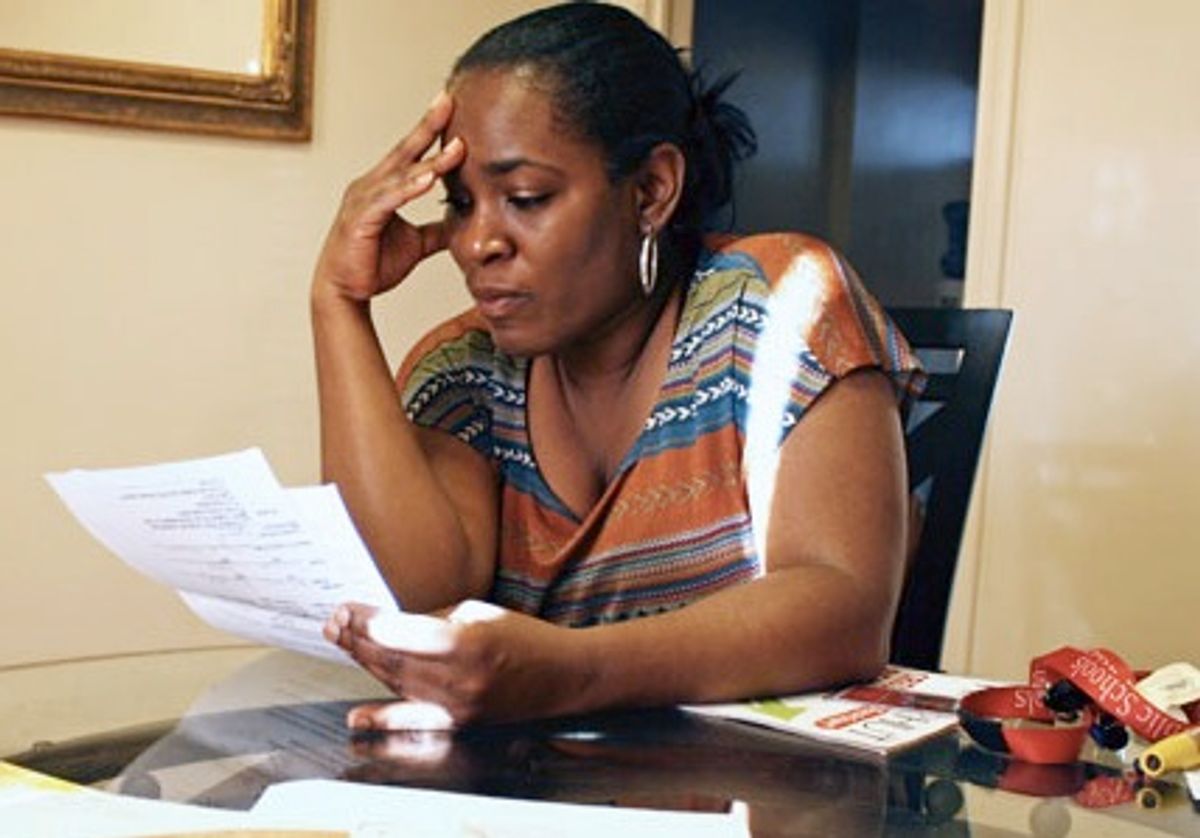

“I had to do a DNA test and swab my cheek like I was a bank robber,” Williams-Bolar says. She reaches for the letter outlining the terms of her probation. “I start with this everywhere I go, because I don’t ever want this to happen to another parent.”

As she moves into the rest of her speech, her voice, already warm and friendly, slows into a smooth, practiced delivery. Her remarks are broad but forceful. She calls for an end to educational inequality and the policies that landed her in jail. She wants more choices for parents whose kids are stuck in under-performing or unsafe schools. In February, she announced the formation of the Ohio Parents Union, part of a growing national network dedicated to giving parents exactly that kind of power. In the past year, Kelley Williams-Bolar has morphed from a desperate mom to an impassioned activist at the center of one of the nation’s most talked about shifts in education reform: the rapidly expanding role of parents in shaping dramatic overhauls of public schools.

Parents are no longer running just the bake sales and attending PTA meetings. All over the country, parents are joining—or being organized by—a movement that aims to spur more competition between schools and, ostensibly, better academic results for kids. Williams-Bolar, radicalized by her brush with the law, has joined the fray.

But as a mother, public school staffer, and now an activist, Williams-Bolar’s ordeal is also a bracing case study of a system that treats high-quality education as a commodity to be earned and parceled out, instead of the public good it’s commonly thought to be. In an era when more and more struggling school districts are turning to the private sector to solve their problems, the question everyone is grappling with now is basic: Can free market principles save public schools?

Tale of Two School Districts

Before her name became a fixture in the local newspaper, and before some activists declared her the “Rosa Parks of education,” Kelley Williams-Bolar was a regular parent trying to look out for her daughters.

“I was just a mom,” Williams-Bolar insists.

She works as a classroom aide for students with special needs in Akron Public Schools, and has been employed by the district on and off in some capacity since 1992. “From Asperger’s to Downs to autism, we deal with it all,” she says. She says that helping students with disabilities comes easy to her in part because her mom did similar work, and it seems true. She still spots students past and present in her neighborhood and tracks their progress. In the parking lot of an Applebee’s, she stops a former student and they exchange warm hellos. “He’s done well for himself, he’s in college now,” she says. She talks about their educational challenges and the progress that they worked to overcome. She rattles off their siblings’ names. It’s work she plainly enjoys.

Williams-Bolar did this work part-time for years, because she was married and in school herself part-time. But after getting divorced and moving into a home with the help of Akron’s public housing authority, she had to begin looking for full-time work to support her daughters. That changed things in her life; suddenly, she wasn’t around as often to mind her daughters, Kayla, then 13, and Jada, then 9.

It wasn’t until someone broke into their home in 2006 that Williams-Bolar started considering other school options. No one was home when it happened, but it left her rattled. “I worried about their safety. I’ve got two girls and they’re growing up. I couldn’t have them walking home alone from school,” Williams-Bolar said, careful not to indict Akron Public Schools, her employer. “I had taken care of my father, and he has taken care of me. I knew that he would be home to look after the girls.”

Williams-Bolar insists she was motivated primarily by these safety concerns when she took her kids out of Akron schools, not by the district’s poor academic performance. But the difference between its record and that of the Copley-Fairlawn School District, where her father’s house is located, is stark.

For the 2010-2011 year, Akron Public Schools met state-prescribed performance goals on just five of 26 categories of performance—such as high school graduation rates and standardized testing scores for reading and math—while Copley-Fairlawn School District met all 26 of its state benchmarks. That same academic year, Akron Public Schools failed to meet its yearly goals for test score improvement, which are set by the federal No Child Left Behind law. It was the seventh consecutive year that the district failed.

In the fall of 2006, Williams-Bolar enrolled Kayla and Jada in Copley-Fairlawn, using her father’s address. The district’s enrollment forms are extensive. It does not have open enrollment; to go to school there a student must either reside within its borders or pay a $9,000 annual tuition. Williams-Bolar, who last year made $28,000, couldn’t afford that kind of fee. So she listed her father’s address on the forms. When it came time to renew her driver’s license, she put down her father’s address as her primary one. Eventually, she also listed her father’s address with her credit union and with her employer. Her daughters were enrolled in the district for two school years, from 2006 through 2008.

By the time Williams-Bolar was indicted for this act, and later sentenced to 10 days in jail, her mug shot had been splashed across TV stations and newspapers for months. Her name would stay in the media for many weeks more as the nation erupted in shock over her case.

Williams-Bolar became a lightning rod for education reformers of all stripes. Petitions were set up by online organizing groups like Moms Rising and Color of Change, and together with one organized by a Massachusetts woman named Caitlin Lord garnered 180,000 signatures calling for Gov. John Kasich to pardon Williams-Bolar. The Taiwanese tabloid news animation group Next Media Animation even documented her story in one of their popular videos—something that Williams-Bolar is bemused by to this day. After being released from jail, she flew out to Los Angeles for a brutal taping of the Dr. Phil Show.

Williams-Bolar recounts all of this while sitting on the front stoop of her home more than a year later. Her life as a parent, and now an activist, is a far cry from the loud headlines her prosecution attracted. As she talks, she’s interrupted by a neighbor who’s amusing his toddler son by rolling his pickup truck in reverse, then neutral, then reverse, then neutral and back again. Together, they roll up and down the driveway, to the boy’s unending delight. Williams-Bolar and the father chat a bit, and the child’s silly, drooling grin is too precious to turn away from.

These days, say “Kelley Williams-Bolar” in Ohio and she represents a whole lot more than this affable neighbor. Most folks know who she is and at least a bit about her case, more if they have strong opinions about what she did for her daughters. Since being released from jail, she’s tried to keep to herself. She says that her political activism has made her unpopular on her job, at Buchtel High School. Still, she moves with ease throughout her community. She is at home in Akron, but fighting to move past the memories of her case.

Williams-Bolar’s attempt to ease her family from Akron to Copley came at precisely the wrong time. Copley-Fairlawn had been waging an aggressive war against parents who committed this kind of school residency fraud. The state consistently rates the district as “excellent,” which is the second-highest evaluation among six possible ratings. That makes it a popular magnet for parents all over the county. To its administrators and many of its parents, people like Williams-Bolar are thieves, literally stealing their “excellent” schools.

Copley-Fairlawn deployed a range of tactics to root out illegal enrollments. Among other things, the district hired private investigators to track parents, which is a common move for school districts taking a hard line on enrollment. In San Francisco, administrators did a similar thing, and forced offending parents to pay the cost of the investigation. In Washington D.C., City Council Chairman Kwame Brown introduced a bill last year that would set up a hotline for parents to report commuters who drive in from out of state and drop their kids off at D.C. schools.

School residency fraud is common, but criminal prosecutions are rare. Still, when they happen, they tend to happen to people like Williams-Bolar. Last year Tanya McDowell, a Connecticut parent who also happened to be a poor black mom, was convicted of larceny for literally stealing her son’s education when she enrolled him in a neighboring school district. “I just want to know: When does it become a crime to seek a better education for your child?” McDowell asked at the time, the Norwalk Patch reported.

School districts have answered by repeating a similar line: their coffers are only so deep, and because so much of public school funding comes from local property taxes, educating out-of-district students is an unfair burden for actual residents.

In 2008, Copley-Fairlawn stepped up its campaign by announcing a $100 bounty to anyone who turned in another family. Williams-Bolar remembers receiving a postcard in the mail announcing the reward to families throughout the district. “I guess it’s not just me, then,” Williams-Bolar recalls feeling. Plus, she was already deeply immersed in a process to make her daughters’ enrollment legal.

But by the time the postcard arrived, the district had been investigating Williams-Bolar for some time. A private investigator assigned to tail her kept watch outside her Akron home for months, documenting her family’s nights spent away from their father’s Copley address.

A Marketplace of Reforms

This past March Williams-Bolar packed her probation letter and headed off to speak at a Connecticut school reform rally. It was to be her most high-profile event as a newly minted education reform activist. The event was aimed at parents advocating Gov. Daniel Malloy’s reform agenda, which is rooted in a school choice model that deregulates public education, and it had drawn education reform celebrities. Michelle Rhee, the former Washington, D.C., schools chancellor who found national fame by carrying the mantle of aggressive school reform, was there. Gwen Samuel, founder of the Connecticut Parents Union, helped organize it.

Williams-Bolar remembers the rally only in hazy, nervous moments. “I had to talk to myself onstage. I said, ‘Look. You’re here for a reason. Get yourself over to the mic and say what you came to say.’ ” The Hartford Courant reported that around 75 people were in the crowd that day. “People told me afterward that I brought people to tears, and I was like, ‘Did I?’ I don’t even remember seeing anyone in the crowd.”

But not everyone has been moved to tears by the controversial Parent Union movement to which Willams-Bolar has lent her story and energy. She says one of her first and most surprising realizations as a new activist has been just how polarized the school reform debate is. “You think everything is for a common cause, but it’s not. I was naïve about the conversation,” she says.

The day the announcement of her new Ohio Parents’ Union hit the local news was a hard one, she says. “The very next day at work, staff didn’t talk to me,” she recalled. “After the Parent Union was announced it didn’t take a lot to realize some of them were opposing it.”

The suite of school reform policies that dominate the mainstream discourse today, from school choice schemes and charter school expansion to teacher evaluation overhauls and the weakening of collective bargaining agreements, are fundamentally grounded in principles of market-based competition. Schools are products, teachers are laborers and students and parents are consumers.

In the case of vouchers, if parents are unhappy with the quality of the education at a school, they can pick up capital via their taxpayer dollars and move to an approved private school. In Ohio, that amounts to $4,250 annually for students from kindergarten to the eighth grade, and $5,000 per year for high school students who take part in the state’s EdChoice program. Ohio’s voucher system caps participation in the program at 60,000 students, but voucher advocates in the state point out that the program is at capacity. Parents are demanding still more options for their children.

Akron Public Schools received a “continuous improvement” designation in the Ohio state evaluations—the third from worst of six possible designations. As a result, it has been losing both students and the state money that comes with them to the voucher program. Four thousand of the district’s 23,000 students now take part in the voucher program, and the district is set to forfeit more than $25 million in state aid this year alone—money that instead has gone to charter schools and private schools.

Some schools in the district are waging an aggressive marketing campaign to hold onto, or win back, families in the neighborhood. In the beginning of the year, Akron Public Schools sent out a 12-page brochure to parents who had removed their children to advertise the district’s offerings, including open enrollment, which makes the district open to even students who don’t live within its borders, and vocational programs and stable schools. Sending out the mailer, the Akron Beacon Journal reported, cost $6,000.

Williams-Bolar says she saw the symptoms of all this in staff meetings in Buchtel Public Schools, where administrators worried about the hemorrhaging of students encouraged staffers to think of the school as a business and to treat parents and students with outstanding customer service.

“I never thought of it that way,” Williams-Bolar says, remembering sitting in a staff meeting perplexed at the idea. The thing is, Kelley Williams-Bolar, who went to ridiculous lengths to be an informed and aggressive education consumer, could well be the poster child for the problems with the paradigm.

The worry of many is that voucher programs and school choice schemes amount to the privatization of public schools. Public tax dollars are being siphoned away from institutions that have historically been considered a public good, and not a commodity. And, critics argue, even the most comprehensive research on vouchers and school choice schemes show that they don’t lead to any meaningful gains in test scores.

Yet to parents fed up with the slow-moving bureaucracy of public schools, school choice schemes have an important narrative appeal. That fact is not lost on choice advocates, who have seized on parents as the new vanguard for pushing school choice, voucher and overhaul plans. The meme of parental empowerment has become a rallying cry, and wedge; who could be opposed to parental empowerment? But the role that some reformers imagine parents filling is narrowly defined, as are the intended reforms.

Privatization and competition in and of itself is not a problem, argues Jeffrey Henig, a professor of political science and education at Columbia University. Outsourcing work that is “harnessed to public objectives” can often help public entities meet people’s social needs, Henig says, and doesn’t always come at the expense of the public good. But systemic privatization can lead to the long-term weakening of democracy when private entities operate without full transparency and outside of the full visibility of the public.

“Part of the problem is the simple notion of informed consumers as distinct from informed citizens,” Henig said. “Both the government and private actors can impinge upon your sense of being able to control your life—most people need to be able to act in both realms, both as consumers and as citizens who act to exercise their rights within democratic institutions, to either create better schools or to more closely regulate private providers.”

Williams-Bolar readily acknowledges that much of this hostile, increasingly arcane debate is new to her. “It’s a bad issue. I wouldn’t know how to even begin to solve it,” she said one afternoon over iced tea. “But I do know we’ve got to stop blaming and get the ball rolling.”

She knows as well that notions of democracy can be abstract ideas to parents who are fed up with their district schools. After pulling her daughters out of Copley schools, during her prosecution, Williams-Bolar enrolled her older daughter Kayla in a public high school and her younger daughter Jada in a private middle school, with the help of Ohio’s EdChoice program. She’s happy with the private school, and doesn’t like the idea that any entity would limit her options.

“Akron Public Schools wants to keep us all here so we can suffer while they get it right,” she said. “My daughters don’t have a second chance at their education.”

Winners and Losers

On Oct. 26, 2007, Williams-Bolar was called into a residency hearing with Copley-Fairlawn district staffers, who presented her with their evidence that she’d been stealing her daughters’ public education. They offered her a set of options, each of which included significant costs. The one that seemed most feasible was for Williams-Bolar’s father, Edward, to claim a Grandparent Power of Attorney, which is a legal designation that would name him as the girls’ guardian for the purposes of their education. A week after the hearing, Williams-Bolar filed for the change in Ohio Juvenile Court. Soon thereafter, she started receiving invoices from Copley-Fairlawn, billing the family $850 a month each for Kayla and Jada. The family refused to pay these bills.

The Grandparent Power of Attorney was eventually denied in June of 2008, because Williams-Bolar’s ex-husband didn’t sign off on the agreement. Life can be messy that way. Still, she was confident she’d attempted to handle the situation in a legal manner. The official denial came just weeks before the school year ended, and she didn’t enroll her daughters back in Copley-Fairlawn schools the following year.

Nonetheless, in October 2009, Williams-Bolar and her father were indicted for falsifying records.

“Kelley’s point was she thought she was trying to get the Grandparent Power of Attorney,” says her attorney David Singleton. “She didn’t think she should pay tuition, which she couldn’t afford anyway. She’s not a wealthy person, which is beside the point.”

Between 2005 and 2011, Copley-Fairlawn schools discovered 48 cases of school residency fraud; Williams-Bolar’s was the only case that ever ended up in court. “Every family except Ms. Williams-Bolar agreed to either pay the non-resident tuition rate, move into the district or remove their children from the school,” Summit County Prosecutor Sherri Bevan Walsh said in a statement to Colorlines.com.

“Ms. Williams-Bolar repeatedly refused to cooperate for many months, thus her case was turned over to my office for prosecution,” Walsh continued, underlining that falsifying information on government documents amounts to a felony offense. Walsh said she was compelled by the evidence. “Ms. Williams-Bolar refused the options presented to her that would have prevented felony charges.”

The Copley-Fairlawn School District insists that its hands were tied as well. In an interview with Colorlines, Superintendent Brian Poe said the district went to great lengths to resolve the issue without legal action, but was forced to hand over evidence to Walsh’s office.

Pinning down exactly who controlled the levers in Williams-Bolar’s case is difficult, as everyone seemed interested in making her a household name. After the presiding judge Patricia Cosgrove handed down her sentence, she said she hoped Williams-Bolar’s case would serve as an example to others. “I felt some punishment or deterrent was needed for other individuals who might think to defraud the various school districts,” Cosgrove told ABC.

Cosgrove spoke an uneasy truth: prosecuting Kelley Williams-Bolar seemed like an easy way to warn off others. But not every family is as vulnerable as moms like Williams-Bolar and Tanya McDowell.

Take the case of Mark Ebner, a Columbus, Ohio, parent who illegally enrolled his children in a neighboring suburban school district. Williams-Bolar’s attorney, Singleton, considers the case illustrative. The Ebner family’s primary residence was a $1 million property just outside the suburban district’s borders. When Ebner found out that private investigators were tailing him, the Columbus Dispatch reported, he arranged for a house swap with relatives inside the district—and then sued the district for spying on him. The same year that Williams-Bolar and her daughters were swallowed up by her court case, the Ebners were handily defeating the rules.

The point, Singleton said, is that school residency fraud—far from being limited to poor black parents—is an activity that parents of all classes engage in. But those with the financial means and social capital to finagle their way out of sticky situations escape the punishments and public shaming Williams-Bolar faced. Like in any marketplace, the more capital you have, the better you’ll fare.

Williams-Bolar doesn’t deny that she falsified the documents, and accepts full responsibility for what she did, but is also still confounded by the whole thing.

“They always treated [my family’s homes] as his house or my house, his house or my house,” Williams-Bolar said. “This is a family house. I help my father pay the bills, I help mow the lawn, I cook and clean for him. The girls have their own room here, I have my own room here.”

In the economy of public education, though, it’s less about squishy ideas of families and homes and more about concrete goods like houses and addresses.

“We have a community that has made it clear to us that they want to provide an education for students who live within our district boundaries,” insists Superintendent Poe. He says that he was particularly disappointed in the way the case was handled by the media. “It was being portrayed as if we didn’t care for the children. But we always sit down with families and are very open. We just want families to be forthright.”

‘I Turn No One Down’

Which is why advocates of parental power and choice all over the country are so compelled by Williams-Bolar’s story. “There are hundreds, if not thousands of Kelley Williams-Bolars in Alabama,” says Marcus Lundy, who works on workforce development and education reform issues in the Birmingham Chamber of Commerce. “The intent is to try to get her to Birmingham to tell her story because her story is the story of many people who live in one area but are limited by their zip code into poor and underperforming schools.”

Lundy wants Williams-Bolar to help advocate for HB 541, a hotly contested bill which would have authorized the creation of 20 charter schools in the state. It passed the Senate, but failed in the House in the waning days of the legislative session.

“If people take inventory of some of the maneuvering that parents have had to do historically to take advantage of the better school systems they would figure that there is no need to hide, to cheat, to lie, to stretch the truth when all they’d have to do is take advantage of parental choice or one educational option of what charter schools would allow,” Lundy says. “And everything would be above the board.”

Williams-Bolar is ready to lend her time to campaigns like Lundy’s—and to any and everything that just may get the “ball rolling,” as she put it. “I don’t say no to anything,” she says. “I turn no one down.”

But her activism is something she has to juggle along with other basic struggles to keep her family afloat. Last week, Williams-Bolar’s father, who Summit County also prosecuted, passed away in prison from complications related to a stroke he suffered in January. Williams spent much of his jail time hospitalized, and had just a month left in his yearlong prison sentence for unrelated fraud charges that arose during the fight with Copley schools.

In September of last year following an international outcry amplified by multiple groups’ online organizing campaigns, Gov. John Kasich, who is a proponent of school choice and voucher schemes, went against the recommendations of the Summit County prosecutors and the Ohio parole board and reduced her convictions from felonies to misdemeanors.

In her father’s living room, she keeps her pardon certificate in the center of the mantle. “I consider these my freedom papers,” Williams-Bolar said. Prior to his passing away, she planned to move back in with him at his Copley Township home so she could be there to take care of him during his transition. Now with his passing, her plans are up in the air.

She still sees her future as an uncertain, but hopeful swath of new possibility. This month the family will celebrate Kayla’s high school graduation. Jada, Williams-Bolar’s younger daughter, is headed to a private high school next year and will qualify for tuition help from Ohio’s voucher program. Williams-Bolar spent months preparing an application to the exclusive Catholic all-girls’ school in Akron, and when the acceptance letter arrived she was decidedly happier than her daughter, who wanted to go to a co-ed high school. The tony girls school is tucked away on a verdant campus, and is a top-performing school.

“I told her even one year here will help set you up for good things to come down the line,” Williams-Bolar said. “I told her, ‘You’ll see.’"

Shares