The much-ridiculed Americans Elect dream officially died last night, when the third way group released a statement saying that no candidate had qualified for its online convention and that the selection process is now over.

In a way, this isn’t at all surprising. The Americans Elect idea was a complicated one that relied on tens of thousands of Americans registering as delegates and participating in a multi-phase online process that would produce a bipartisan national ticket. It also required prospective candidates to go public with their interest and submit themselves to this process with no guarantee of success. In the end, not enough delegates signed up, and only one real candidate – former Louisiana Governor Buddy Roemer, who was treated as a non-entity during his bid for this year’s GOP nomination – stepped forward.

In a broader sense, though, it is somewhat surprising there won’t be a viable third party candidate in the 2012 presidential race. Toward the end of last year, it was starting to look like the basic ingredients for one would be in place: a wounded incumbent with a sub-50 percent approval rating, a sense that the opposition party’s candidate is an unacceptable alternative, and pervasive popular anxiety.

This was the formula that gave rise to the two third party presidential efforts that got the most mileage in the modern era: John Anderson’s in 1980 and Ross Perot’s in 1992.

Anderson, like Roemer, had originally sought the Republican nomination, although he gained more traction, carrying the mantle for moderate/liberal Republicanism and nearly winning a few primaries. When it became clear that Ronald Reagan would be the nominee, Anderson bolted the party and launched an independent bid. The logic was sound enough at the time: Reagan had the image of a dangerous, trigger-happy extremist, and just 16 years after the Goldwater debacle it was widely assumed that he was unelectable. At the same time, Jimmy Carter’s approval ratings were falling to the low-30s; the sentiment to get rid of him was widespread.

So there seemed to be a gigantic opening for a middle-of-the-road third choice, and sure enough, Anderson showed early polling strength, climbing to over 20 percent in the spring of ’80. He even made it into a one-on-one nationally televised debate with Reagan in September, with Carter boycotting (under the belief that it would further legitimize Anderson and cause him to pull even more votes from Carter). But by October, Anderson’s support was in decline. The sentiment to fire Carter remained strong, but as Reagan gained exposure, swing voters began to regard him as an acceptable alternative, and to see Anderson as a spoiler. Other Anderson supporters defected to Carter, simply to stop Reagan. In the end, Anderson secured 5.7 percent – a number that understates his prominence in the ’80 race.

Perot also capitalized on a deeply unpopular incumbent, George H.W. Bush, whose approval rating had fallen to the low 40s by early ’92. Perot first floated the idea of running on “Larry King Live” in February, and it quickly caught fire with an electorate that was sick of the incumbent but troubled by the scandals that seemed to continually jolt the presumptive Democratic nominee, Bill Clinton. By the late spring, Perot was consistently running in first place in national polls, with Clinton a distant and forgotten third.

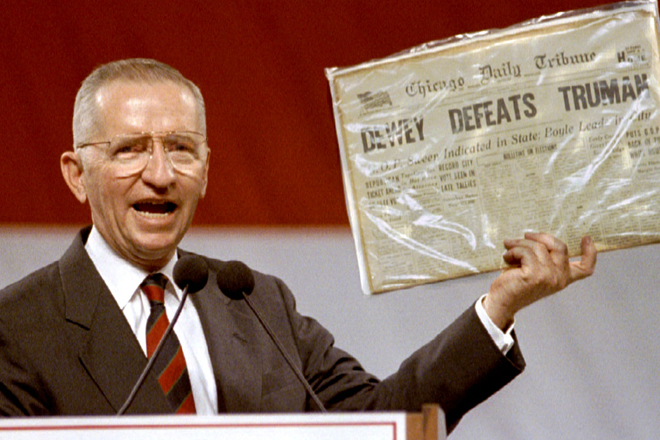

But Perot didn’t hold up to scrutiny, while Clinton began repairing the damage to his image. In mid-July, after falling out of the lead, Perot abruptly withdrew, helping Clinton to emerge from the Democratic convention with a lead of well over 20 points over Bush. That lopsided advantage persisted through the summer and into the fall, when Perot reentered the race and qualified for the debates. The Texan’s performance was strong enough that he finished with 19 percent of the popular vote, the best national showing for a third party candidate since Theodore Roosevelt in 1912.

(Perot, of course, tried again in 1996, but while his performance that year – 8 percent of the vote – technically exceeded Anderson’s from 1980, he was locked out of the debates and had little impact on the campaign.)

There are some obvious parallels between today’s environment and the environments that created Anderson and Perot. And when it seemed possible last fall that the GOP would anoint Rick Perry (or another culturally polarizing ideologue) as its nominee, the idea that there’d be a viable third choice this year – whether through Americans Elect or some other vehicle — made sense.

But Mitt Romney’s emergence as the GOP’s presumptive nominee changed the equation a bit. It’s absolutely true, as Jamelle Bouie detailed in the American Prospect this week, that Romney as president would probably end up functioning as an instrument of the far-right forces that lead his party. But, thanks in no small part to all of the moderate and liberal positions he took to win office in Massachusetts years ago, Romney has the image of a moderate, and is often described as one in the press. Plus, his style is often mocked, but that’s because he can seem wooden and awkward, not because he’s unusually abrasive or inflammatory. It’s not surprising he’s been able to substantially improve his personal favorable rating since securing the GOP nomination. The third party formula calls for an opposition party nominee that arouses instant alarm among swing voters, but Romney is pretty close to being a generic Republican candidate.

So there’ll be no Ross Perot or John Anderson this year. But if you still want to have fun with third party mischief scenarios, you’re not entirely out of luck: former Virginia Rep. Virgil Goode is running as the Constitution Party’s candidate; what if he peels off a small but consequential share of the vote in his home state, aka the premier swing state?! There’s also Gary Johnson, who also got the Roemer treatment during the GOP primaries and is now running as a Libertarian. A new poll has him at 7 percent in the liberty-loving swing state of New Hampshire…