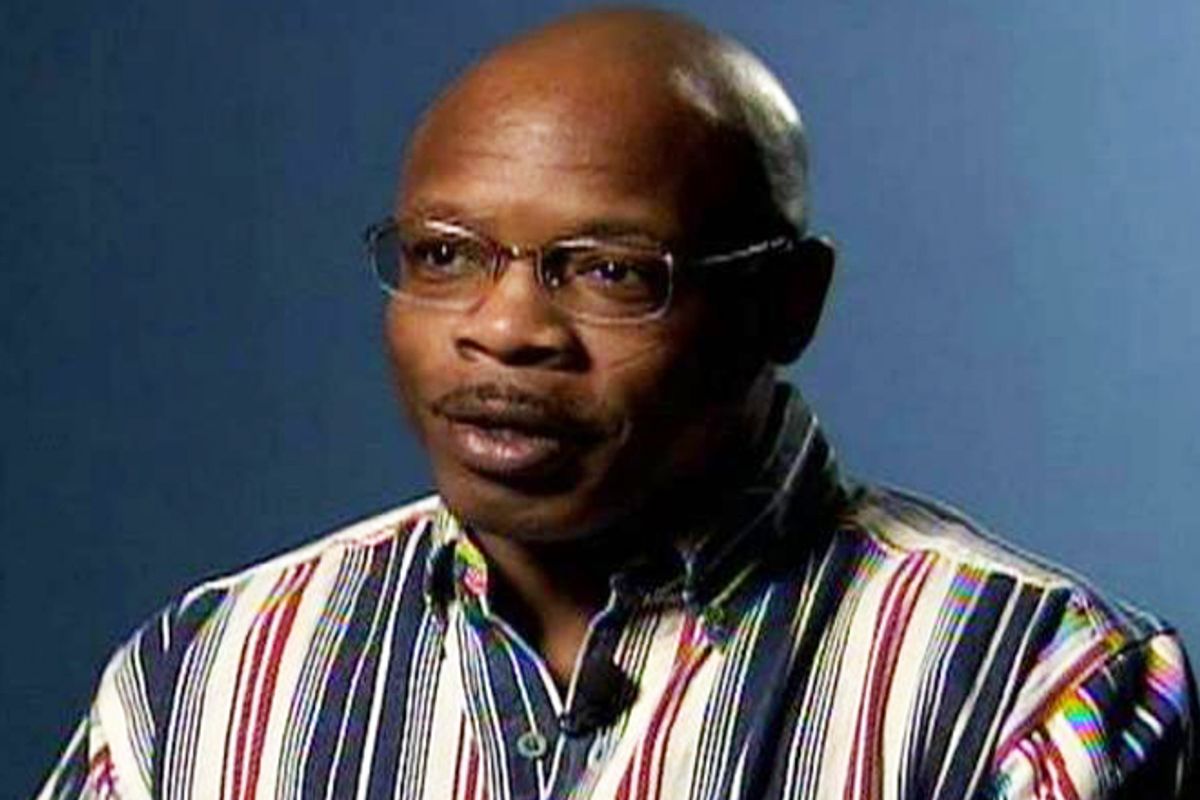

Glen Edward Chapman, or “Ed,” was exonerated in 2008 after spending 15 years on death row for crimes he did not commit. Though North Carolina is one of the 27 states with statutes that provide some level of compensation for the wrongfully convicted, the state continues to refuse Chapman any compensation for the loss of his freedom, reputation, family, friends and much more.

Chapman was sentenced to death in 1994 at the age of 26 for the murders of Betty Jean Ramseur and Tenene Yvette Conley in Hickory, N.C. After more than a decade of court appeals, Superior Court Judge Robert C. Ervin ordered a new trial based on revelations that detectives “lost, misplaced or destroyed” several pieces of evidence that pointed to another suspect. It was also discovered that lead investigator Dennis Rhoney lied on the witness stand at Chapman’s original trial. Shortly thereafter, the district attorney dismissed all charges against Chapman due to lack of sufficient evidence leading to his exoneration in 2008.

Chapman is just one of a growing number of wrongfully convicted inmates who have been cleared thanks to criminal justice reforms and new DNA testing laws put in place over the last decade. But oftentimes the hardship doesn’t end there.

In 2007, the New York Times interviewed 137 former prisoners exonerated by modern DNA testing methods and found that half were “struggling — drifting from job to job, dependent on others for housing or battling deep emotional scars. More than two dozen ended up back in prison or addicted to drugs or alcohol.”

According to a 2009 report by the Innocence Project, an organization devoted to exonerating the wrongfully convicted, an astounding 40 percent of people exonerated by DNA testing have received zero compensation, due in part to the 23 states around the country that do not offer assistance to the wrongfully convicted. That leaves exonerees like Alan Northrop, who lost 17 years behind bars in the state of Washington, with little to no help in rebuilding their lives.

Even in states that do offer compensation, the amount is often woefully inadequate in helping exonerees reestablish themselves, though compensation varies by state ranging from $20,000 in New Hampshire regardless of the years spent behind bars to $80,000 per year of wrongful imprisonment in Texas.

Most state compensation statutes, however, include conditions for eligibility. Last year, Texas refused to compensate Anthony Graves the $1.4 million he would have received for the 18 years he spent on death row because the judge did not include the words "actual innocence" on the document ordering his release. Texas reversed its decision only after nationwide media attention led to a massive public outcry.

In North Carolina, the exonerated are eligible to receive $50,000 for each year of wrongful imprisonment capping out at $750,000 but only if they are granted a pardon of innocence by the governor who is not required to give a reason for her decision. Chapman filed a pardon request in 2009 but a decision has yet to be made. The office of North Carolina Gov. Bev Perdue did not respond to a request for comment.

Chapman’s experience is consistent with statistics from the Innocence Project that show it takes an average of three years to secure compensation. Meanwhile, the wrongfully imprisoned face an uphill battle almost immediately upon release, starting with where they will sleep that night and how they will get their next meal. Only 10 states even offer the kinds of services — housing, transportation, education, healthcare, job placement, etc. — crucial to helping exonerees transition back into society as free citizens.

Chapman was not notified he was going to be released until the day he was freed. On April 2, 2008, a guard told him to “Pack up” and 10 minutes later he was out the door. No one asked if he had a ride or a place to stay.

Luckily he had help from Pamela Laughon, a college professor and chairwoman of the psychology department at the University of North Carolina, who spent eight years working on Chapman’s appeal as a court-appointed investigator. The two immediately clicked when they met and have been inseparable since.

Laughon told Salon she was shocked her client was released with just 10 minutes' notice and no ride or money. “Years ago they used to let them out with at least a bus ticket,” she says. Nevertheless, the two had already decided that if and when Chapman was released he would live with Laughon until he got on his feet.

That meant Chapman would have to move to Asheville, N.C., which worked out for the best because he did not want to return to Hickory. “When I go back to Hickory the hair on my neck stands up,” says Chapman. The town reminds him of the trauma from his trial when family members testified against him and the time he spent incarcerated instead of watching his two young sons grow up.

Laughon was happy to help. “I had lawyers calling me from all over the state asking me if I was nuts. I spent eight years trying to get this man released. There was no way I was going to drop him off at a homeless shelter or the projects where he grew up,” she told Salon.

With Laughon’s assistance, Chapman set up a checking account, got a driver’s license for the first time, found housing, learned how to use a cellphone and more.

She helped him manage his finances, which quickly dwindled given that he hadn’t received an income in 15 years. Over a decade in prison led him to mishandle the money he did have because, Chapman says, “I was so unused to having things that I wanted to buy everything. I went shopping crazy.” It was moments like this that having Laughon’s support was crucial to Chapman’s ability to readjust to society as a free man.

Laughon also went on job interviews with him to help explain his background to prospective employers. “I’m a college professor and chair of a department, so I have some cred,” she says. “He’s a black guy in the south. If he told an employer ‘by the way I was wrongfully convicted and spent the last 15 years on death row,’ people would look at him like he was crazy and laugh.”

With help from one of Laughon’s students, Chapman found a job at a hotel a few weeks after his release. Four years later, he still works there, which he says is the longest he’s ever held a job.

Still, life is a struggle. Laughon argues that Chapman needs the compensation because, “He’s stuck in minimum wage, being paid the lowest legal amounts you can pay a human being.”

The pardon of innocence pending before Gov. Perdue is important to Chapman not just for the compensation but also because it would be an official declaration of innocence. Laughon calls his current predicament “a no man’s land between not being guilty or innocent.”

Rev. Dr. T. Anthony Spearman, a pastor in Hickory and third vice president of the North Carolina NAACP, points out that without an official declaration of innocence, “His family is still at odds with him, not knowing whether he’s a criminal or not. The stigma of being a felon is still on him.”

Spearman went on to compare wrongful conviction to a crime in and of itself. “To be incarcerated, locked up for 15 years wrongfully, is to me a criminal act and the state needs to make up for that,” he told Salon. “The government needs to go head over heals to make sure these men receive apologies and make sure that they can get on with their lives meaning compensation, education, whatever they need to survive.”

Jean Parks, an active member of Murder Victims' Families for Reconciliation (her sister was murdered) and People of Faith Against the Death Penalty in Asheville, agrees that Chapman needs be pardoned but feels that monetary compensation for the wrongfully convicted does not go far enough. “Money should be a part of it to help cover for lost wages and lost opportunities but the state’s response should go beyond that,” says Parks. “It should include an official apology and some social services to help the person get reacclimated to society, find a job, and reestablish oneself as a productive member of the community.”

Laughon argues that states should provide a “life coach” to do for the exonerated what she did for Chapman, which she describes as “somebody that’s going to navigate all the many day-to-day things like managing a bank account, how paychecks will be taxed, and the other kinds of life skills you and I do second nature.” She believes her experience with Chapman serves as a successful case study of the “life coach” approach.

In the meantime, Chapman has an interview with the clemency office on May 30, a signal that Gov. Perdue will likely come to a decision soon. He is determined to stay positive no matter what the outcome and insists he has no bitterness toward the people who put him on death row. “I can forgive. That doesn’t mean I have to forget,” says Chapman.

He upholds that principle by traveling across the state when he can to speak about his exoneration and bring awareness to the flaws in the criminal justice system. He admits he was not aware of the death penalty before his conviction but “now that I do know, I’m going to do everything I can to put an end to it.”

Since his exoneration, Chapman has written a book called “Life After Death Row.” His next book, “Within These Walls,” will be released later this year and includes his diary entries from death row. He says, “It’s going to be a tear-jerker.” Chapman will also be featured in an upcoming episode of B.E.T.’s "Vindicated," a documentary-style television show that tells the stories of exonerated prisoners.

If he receives compensation, Chapman hopes to open a bed and breakfast. He also dreams of one day opening a shelter for at-risk women.

Chapman acknowledges that none of this would be possible without someone like Laughon in his life. “When I first met Pam it was like meeting an old friend for the first time. To this day, she’s like my big sister,” he says. “She’s been there for me from start to finish. I don’t think I would have made it without her.”

Shares