“In this hour of the ever-changing season, may our tears not douse the fire in our hearts.”

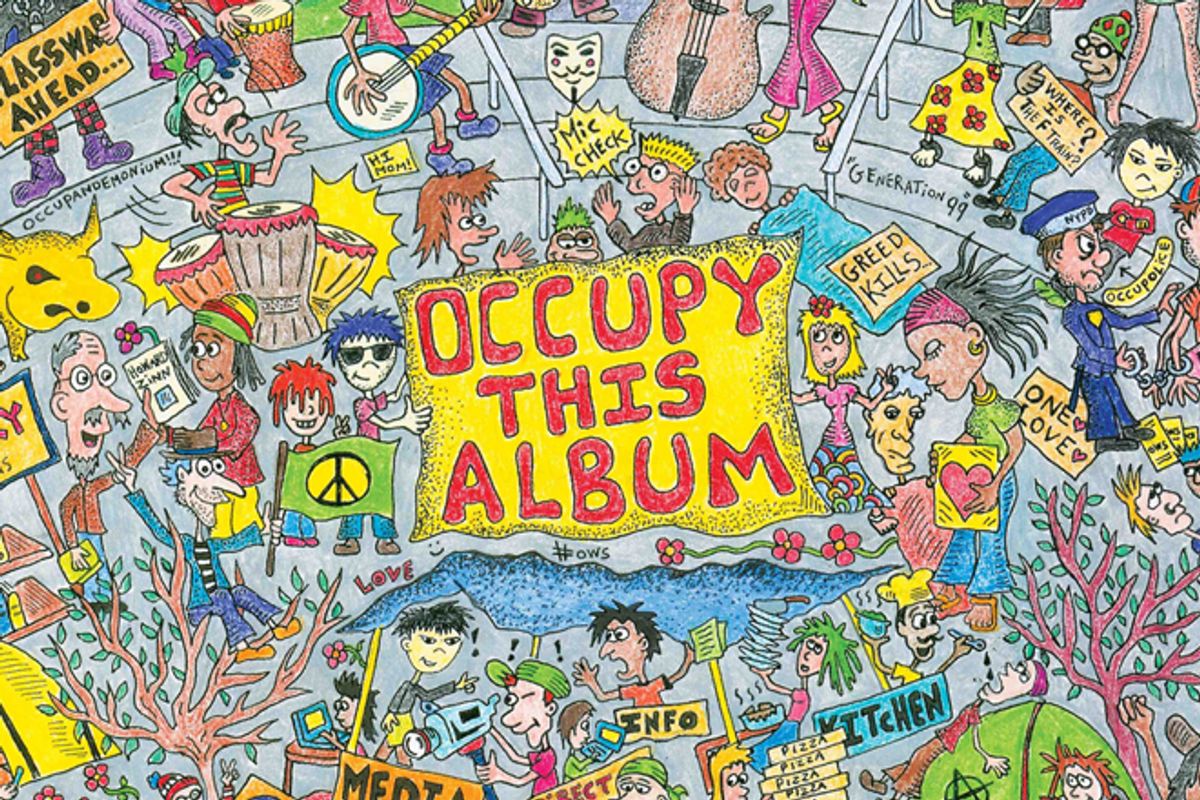

That’s a guy named Michael Pless singing “Something’s Got to Give.” Even without hearing the song, you can surely imagine the essential elements: Plaintive acoustic strumming, an earnest vocal, and an air of polite outrage to match the stilted syntax and hoary platitudes. Welcome to "Occupy This Album," the collection of protest-minded songs released by Occupy Wall Street. Sprawling across four CDs and a slew of bonus digital tracks, this behemoth set includes 100 (why not 99?) new and previously released tracks from artists representing a range of generations, genres, backgrounds, settings, and styles. Folkies join hands with rappers; ominous post-rock marches alongside peppy radio pop. There’s spoken-word poetry, tribal percussion, earnest singer-songwriter fare. Even a bit of jazz.

Especially with Occupy reaching a crossroads in summer 2012 — a time when it needs to reassess its ideals, its accomplishments, its methods and its artifacts — "Occupy This Album" plays like a state-of-the-field survey of the protest song. From Jeff Mangum covering the Minutemen to the anonymous drum circles that soundtracked the demonstrations in real time, music has been a constant presence in the movement, although it’s not quite clear what role it has played. The new album portrays a movement with a broad scope and an admirably varied constituency, but the same criticisms that have been leveled against Occupy can also be applied to "Occupy This Album:" There is general unease but no clear direction forward. There is outrage but no plan. There is deep feeling but no clear message.

Ostensibly, there should be something on "Occupy This Album" for everyone to love, but that also means there is more than enough here for everyone to hate. It’s an unwieldy tracklist, almost daring you play it front to back. Of course, it’s pointless to review a 100-track release the same way you would approach a studio album, where functionality and some sense of logical progression are crucial. But there’s no consistent development of political or musical ideas weaving these songs together, nothing to link them or to justify this particular sequencing. As a result, "Occupy This Album" cannot make a statement as an album. In one sense, this release mirrors the leaderless ethos of the movement, which stridently preserves the democracy of the demonstrations. While that idea has certainly energized the Occupy protest, it makes for an amorphous blob of music and a messy, often frustrating listening experience.

But they mean well, right? It’s a charity album after all, with each disc sold separately and with all proceeds benefiting Occupy directly. You’d probably be better off contributing directly to the cause and just making your own mix of politically minded music. You might even have some of these songs in your iTunes already, although why you’d want to include Lucinda Williams’ drippy “Blessed” or Mogwai’s interchangeable “Earth Division” is beyond me.

The music that actually is new — that purports to find direct inspiration in either the righteousness of the demonstrators or the plight of the 99 percent — is generally unimaginative, hokey, disappointingly safe. Most of these artists address these economic issues either through narrative or through high-minded rhetoric. The latter produces the most lackluster results: Jackson Browne’s “Which Side Are You On?” which he has been touting for several months now, turns out to be political white noise, a gentle fist bump to the like-minded that barely puts across either side of the debate. At least it’s better than My Pet Dragon’s epiphany on “Love Anthem”: “Only love can save us now.” To their credit, they sing it like they might actually believe it.

The storytellers have more success, if only because they’re willing to entertain a bit more grit, a bit less blind hope. Featuring Joan Baez and Steve Earle, James McMurtry’s “We Can’t Make It Here” sounds downright curmudgeonly as it surveys the state of the working class in an economy that regularly sends its manufacturing jobs overseas. The song, however, goes a bit overboard when the trio decry litterbugs and graffiti artists.

One of the true standouts among these 100 tracks is Richard Barone’s ditty “Can I Sleep on Your Futon?” about a veteran-turned-singer who couch-surfs from one generous soul to the next. The verses are specific and soulful, as through he’s derived them explicitly from lived experience, and in that regard, the song could function as commentary on the music biz. But Barone stumbles over that massively awkward chorus, “Can I sleep on your futon?” It’s hard to imagine a crowd of protesters singing along.

If there is one overarching theme here, it is, vaguely, “history.” The past informs and even defines this music. Even the very idea of this type of compilations seems like a throwback to the CD’s heyday in the 1990s, when seemingly every charity, from NARAL to the Red Hot Organization, had its own release. It’s an impression reinforced by much of the music, especially hip-hop tracks by Born I Music and George Martinez & the Global Block Collective, whose lyrics and beats sound like they were scavenged from 1994. (For a better example of how hip-hop can address political themes, check out Killer Mike’s new track “Reagan.”)

Of course, there is a lot of folk music on "Occupy This Album." That style has proved one of the most politicized musical forms of the 20th century, as lefties in the 1930s and 1940s adopted labor songs as battle cries. Clean-scrubbed, buttoned-up folkies like the Kingston Trio had some chart success in the 1950s, but they were quickly rendered obsolete by the Village bohemians reimagining the music as a vehicle for countercultural sentiments. That’s the model so many Occupyers are reverently appropriating, never suspecting that it might not be a natural fit for 21st-century dissent. The folk revivalists of the 1960s drew from the past as well, but took pains to update the music to the times: The mere fact that Dylan wrote new songs in this old style was revolutionary, alienating an older generation of folkie purists.

"Occupy This Album" obviously represents a counterculture, but too many of the artists are too caught up in role playing the past, which seems like an especially boomer enterprise. Michael Moore (yes, that Michael Moore) performs the most chipper version of “The Times They Are A-Changin’” imaginable, one that seems wholly unaware of the gritty realities of 2012, much less of 1964. (The less said about his skiffle version of the song, a hidden track on disc four, the better.) Perhaps the one artist who understands how to plumb history for present-day relevance is Loudon Wainwright III, whose wry “The Panic Is On” updates an 80-year-old tune originally penned by Hezekiah Jenkins (the cover originally appeared on Wainwright’s album "Ten Songs for the New Depression"). It’s an unusual artifact from the early 1930s, but there’s a sneaky observation about class disparity that sounds more disgusted and potent than anything else on the album.

Perhaps the worst thing that can be said about "Occupy This Album" is that the music is deeply conservative. There are so few moments that grab your attention or make you see the world differently. When Occupy already seems to be in danger of losing momentum, it’s hard to say whether the movement has failed to inspire these artists or the artists have failed to document the movement.

Shares