Here's a startling news item: "The Intouchables," a lively if largely predictable Parisian comedy about a wealthy quadriplegic and his ne'er-do-well immigrant caretaker, has become the biggest international success in the history of French cinema. Indeed, according to some sources -- and these things are notoriously difficult to measure on a global and historical scale -- "The Intouchables" is now the biggest non-Anglophone film of all time, with a worldwide gross approaching $300 million.

But beyond the business headlines, what's really fascinating about "The Intouchables" is the way it exposes the gulf in racial attitudes between France and the United States, along with another gulf that's just as wide, the one that has film critics and cinephiles on one side and popular audiences on the other. Viewers in numerous countries have eagerly devoured this feel-good fable about two men of different races and classes who forge an improbable friendship (dubbed by some wags "Driving Monsieur Daisy"). While the audience for foreign-language film is inherently limited in America, there's no reason to believe it won't do well here also. At the same time, heated transatlantic debate has erupted over whether "The Intouchables" traffics in offensive racial stereotypes, with Variety critic Jay Weissberg writing an uncharacteristically angry review that accused the film of "Uncle Tom racism" and compared the Senegalese caretaker character to a "performing monkey."

When Harvey Weinstein first acquired "The Intouchables" in the wake of its smash success in France, he clearly imagined another dark-horse Oscar contender, in the wake of "The Artist." The film has racked up audience awards at film festival after film festival, and currently stands at No. 93 on IMDb's user-generated "Top 250" list. Omar Sy, the charismatic Afro-French actor who plays Driss, the caretaker, won this year's César award (the French Oscar equivalent) for best actor, beating out actual Oscar winner Jean Dujardin. But with the looming possibility that "The Intouchables" could spark a divisive, soul-searching racial debate -- which was precisely what squelched the Oscar hopes of "The Help" -- those expectations have been downplayed. (That isn't why "The Intouchables" is being released this week, with Weinstein and most of the film-biz aristocracy in Cannes, but the coincidence is oddly useful.)

Let me come clean right now and tell you that I enjoyed "The Intouchables" quite a bit. If you're looking for a lightweight summer change of pace, with just a smidgen of Continental flair, here it is. Both Sy and co-star François Cluzet (of the hit thriller "Tell No One") are marvelous, the former playing a guy who's constantly in motion, both physically and psychologically, and the latter playing a depressed and repressed guy who literally can't move, but whose real imprisonment has more to do with his spirit than his spinal cord. Don't go expecting serious French art cinema, please; those who have described this movie as something like a mid-'80s Eddie Murphy comedy dressed up with classy Parisian settings are correct. But here's the question, and I can't answer it for you: Is that such a bad thing, in itself?

Once is not enough for a movie that's made this much money, of course, and Weinstein already has an American remake in the works, possibly to star Colin Firth as stick-up-butt wheelchair dude. The real Eddie Murphy has gotten too old to play the loosey-goosey, pot-smoking sidekick, but there's no shortage of guys who could do it: Jamie Foxx is the default setting these days, but I'd go for the suddenly hot Kevin Hart from "Think Like a Man." I'm not claiming it's aesthetically or sociologically valid to remake a French movie that already feels like a reheated Hollywood throwback, by the way. I'm saying it's a cruel reality, like Dutch elm disease or Adam Sandler, and there's no way to stop it.

To get back to the case at hand, I do understand what the haters find so offensive about "The Intouchables." (The infelicitous English title, by the way, reflects the fact that they couldn't really get away with calling it "The Untouchables," could they?) I was pretty taken aback by Weissberg's vituperative review, and I tend to believe that "Uncle Tom" is one of those expressions that white people should pretty much never use. On the other hand, I can only applaud him for abandoning the balanced, analytical mode of trade-magazine criticism and saying exactly what he damn well thinks. (As for comparing a black man to a monkey -- well, I understand what Weissberg was getting at, but it's an error of rhetoric, the sort of comment that makes nuance and context disappear.) And I know for sure, from hearing friends and acquaintances in and around the movie business complain about this film, that Weissberg is not alone.

I believe that Olivier Nakache and Eric Toledano, the writing-directing duo who made "The Intouchables," are innocent of any bad intentions. In fact, "innocent" isn't a bad word overall, for this movie and the worldview it represents. The French may pride themselves on being the most worldly and sophisticated of all people, but the debate in France about race and immigration and multiculturalism -- which ramped up sharply after the suburban riots of 2005 -- can sometimes sound strikingly naive to American ears. Until very recently, mainstream French opinion has resisted thinking about the nation in anything except homogeneous terms, despite growing Arab and black minorities (both immigrant and native-born) and evident social problems with segregation and discrimination. (The French census, for instance, is prohibited from collecting data on race or religion, so no one really knows how many French people are black or Islamic.)

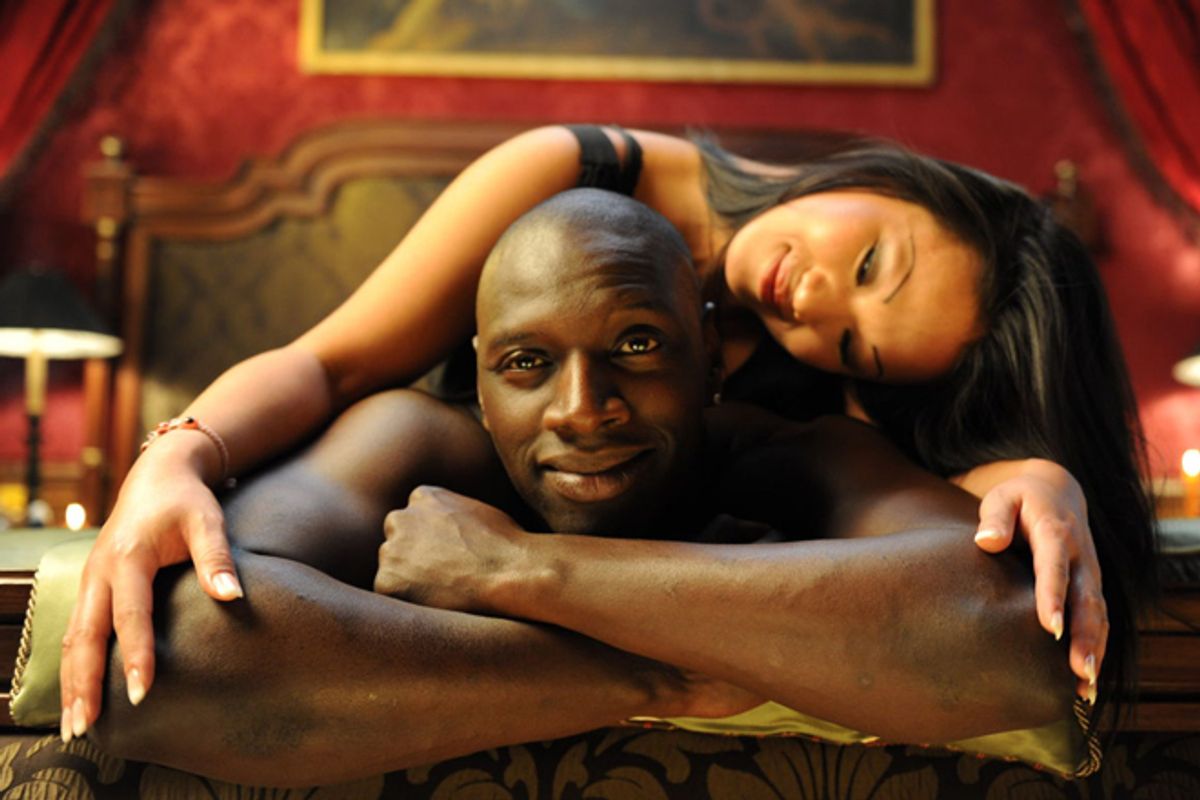

There can be no question that the characters in "The Intouchables" are stereotypes, in the broad sense. Cluzet's character, Philippe, is an aristocratic zillionaire who lives in an astonishingly luxurious flat in central Paris. Since being injured in a paragliding accident, he's lived inside a cocoon of money and privilege, surrounded by antiques and modern art and a bevy of assistants. Sy's character, Driss, is easygoing, good-hearted, lustful and uncultured, and his passions run toward pretty girls, getting high and vintage American R&B. Philippe hires Driss specifically because Driss doesn't particularly want the job -- he only shows up to get a signature for his benefits card -- and feels no pity for Philippe.

Which is actually a pretty good reason. You get where this is going, most likely: Driss is a pretty inept caretaker, at least at first, but is the only person Philippe knows who will relate to him man to man. There's a bit of borderline-homophobic humor about their enforced intimacy; there are interludes with hookers and fast cars and late-night conversations fueled by booze and marijuana. Driss learns to like Mozart and modern art; Philippe learns to get down with Earth Wind & Fire and gets some valuable tips about chicks. It's probably fair to summarize this movie as being the story of a paralyzed white man who needs the help of a younger, stronger, more virile black man to reconnect with his own masculinity, and if you want to say that narrative reflects an underlying latticework of racist attitudes, I won't argue with you. Then there's the complicating factor that in the real-life story on which "The Intouchables" is based, the caretaker was of Algerian origin, and hence Arab rather than black. (The filmmakers have said they wanted to cast Sy, and built the story around him, but it's certainly possible to render other interpretations.)

But one can concede all of that while still agreeing with French historian and multicultural activist François Durpaire, who has responded to Weissberg by arguing that the huge success of "The Intouchables" is likely to have positive effects in Europe's emerging discussion of race and culture, even if the movie relies on crude generalizations. (Durpaire adds that if "The Intouchables" is offensive, so were the "Beverly Hills Cop" movies.) Movies are not meant to be seminars in sociology, after all, and most viewers will receive "The Intouchables" as an upbeat story about two guys from vastly different circumstances who turn out to have a lot in common and help each other, etc., rather than a lesson in racial semiotics.

Perhaps the strongest endorsement for "The Intouchables" has come from aging French ultra-nationalist Jean-Marie Le Pen, who has described it as an allegory about how the future of his nation depends on disenfranchised young immigrants from the suburbs. He thinks that's a "dreadful" vision, mind you -- but, seriously, who knew that guy was so smart?

"The Intouchables" opens this week in New York and Los Angeles, with wider national release to follow.

Shares