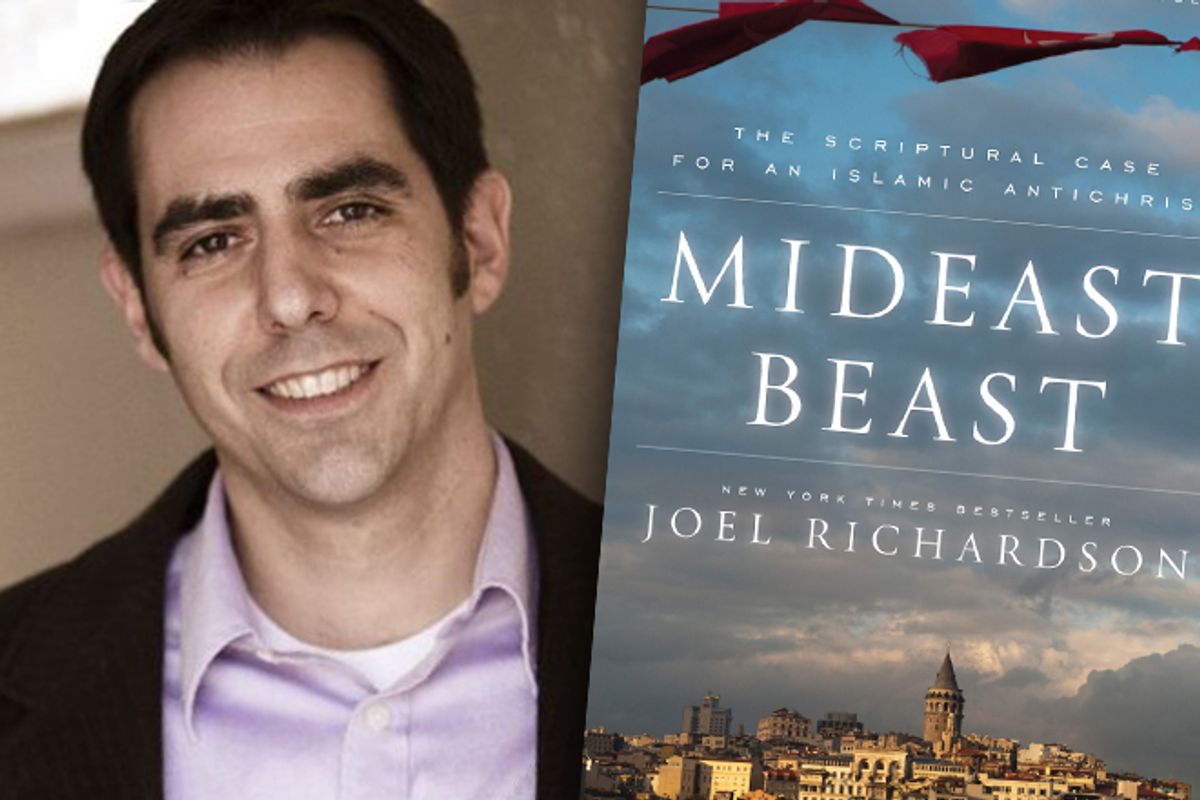

Joel Richardson is unknown to most Americans. He has received virtually no mainstream media coverage, nor has he been the subject of any public controversy. Yet he is a key figure on the religious right’s sizable but oft-overlooked wing that believes the Islamic threat to be the greatest danger the world faces. His 2009 book "The Islamic Antichrist: The Shocking Truth About the Nature of the Beast" became an unlikely New York Times bestseller despite not benefiting from any substantial publisher promotion or press treatment. He has been discussed in the New York Daily News, written for World Net Daily and David Horowitz’s FrontPage Magazine, and appeared frequently on Glenn Beck’s hugely popular (but now thankfully defunct) Fox show as well as on the Dennis Miller Show. And now Richardson has a new book coming out called "Mideast Beast: The Case for an Islamic Antichrist", which promises to give him an even larger following.

Richardson first began publishing Islamophobic tracts with his 2006 book, "Antichrist: Islam’s Awaited Messiah" (you may notice a theme here). Like all four of his books, "Antichrist" makes the case that Islam’s message is the virtual embodiment of the biblical antichrist. It explains how the antichrist described in Christian texts is identical to the figure many Shiite Muslims believe will guide believers in end times. “I believe Islam is destructive to the souls and mankind in general — it’s a destructive and crushing force,” Richardson says in a phone conversation. “No other religion or ideology has so canonized anti-Christian theology than Islam.” He says frankly that he hates Islam but loves Muslims “passionately.”

Only with "The Islamic Antichrist" did Richardson gain a huge audience, however. “It was in September 2005 that Mahmoud Ahmadinejad came to the United Nations and made his initial statements praying for the coming of the awaited savior of humanity and so forth, and I think that’s when the Western media started asking questions about what this guy was talking about,” Richardson says. It was certainly when apocalyptic Christians became obsessed with what Ahmadinejad was talking about. An entire segment of the religious right is devoted to exposing what it believes are the world-dominating desires of Muslims around the world. According to 700 Club host Pat Robertson, Islam is not even a religion. “It is a worldwide political movement meant on domination of the world,” Robertson said in 2007. “And it is meant to subjugate all people under Islamic law.” The conspiracy-oriented Beck devoted entire episodes of his show to outlining Richardson’s revelations.

In some ways, Richardson’s success is similar to that of the Left Behind series. The 16 novels in the series about Christian end-times have sold more than 65 million copies, despite their being almost completely off the radar of the dominant literary culture. The apocalyptic Christian wing of the Republican base gets little media attention because it is not well represented among major political or media figures (at least openly). Only Tea Party standard-bearer Michele Bachmann puts a face to it. But it is an extremely vital, energetic part of contemporary conservatism. “[M]illions of voters, like their Depression-era predecessors, fear that the time is short,” writes Matthew Avery Sutton, author of a book on the evangelical movement.

According to Matthew Duss, an expert on the Middle East at the Center for American Progress, these Christians are a reliable source for supporting hawkishness and military intervention in the Middle East, convinced as they are that Islam is the greatest source of evil in the world. “During the Cold War, the Soviet Union played the role of the enemy of Christianity, but now Islam has taken on that role,” he says. Indeed, Richardson appeared in a Glenn Beck video inflating the threat a nuclear Iran poses to Israel. In addition to the hardcore Pat Robertson types, there is a “larger group that nominally pays attention to this” type of apocalyptic rhetoric, says Duss. “Though they were not initially a huge part of it, they came to be represented in greater numbers in the Tea Party movement. There’s definitely a big audience for this stuff.”

Richardson is “coming up and making the rounds” in this subculture, Duss says. Richardson’s website features endorsements from several pastors and professors, as well as Robert Spencer, the leading anti-Islamic intellectual in the United States. Perhaps not surprisingly, Richardson has no claims to be an expert on Islam. He converted to Christianity in 1991 and attended a small bible school in 1993. He pursued a degree in civil engineering and started a campus ministry doing outreach to Muslims. After his decorative painting business succeeded, he started working for Answer-Islam.org, a Christian site that aims to recruit Muslims and offers theological challenges to Islam. He says he “essentially read every book in existence pertaining to the issue of Islamic Eschatology (in English)” and began writing his first book in 2003 to make the information accessible to a wider, mainly Christian readership.

In addition to his attacks on Islam, Richardson targets President Obama. He has written on the commonalities between the antichrist and Obama, with both sharing plans to redistribute wealth. Richardson blames Obama for letting Egypt fall to the forces of darkness taking over the Middle East. Such claims are surely part of the reason for Richardson’s increasing popularity.

Whatever the reasons, Richardson is likely to increase as an important figure in the Christian anti-Islamic movement as he keeps writing. Relative to many of his competitors, he is well-versed in scripture and is a comprehensible writer. His preachings about loving Muslims while despising Islam make him seem grounded in Christian teachings and compassionate in his beliefs. But his virulently bigoted views on Islam make him a dangerous character — and one that has found many adherents on the religious right.

Shares