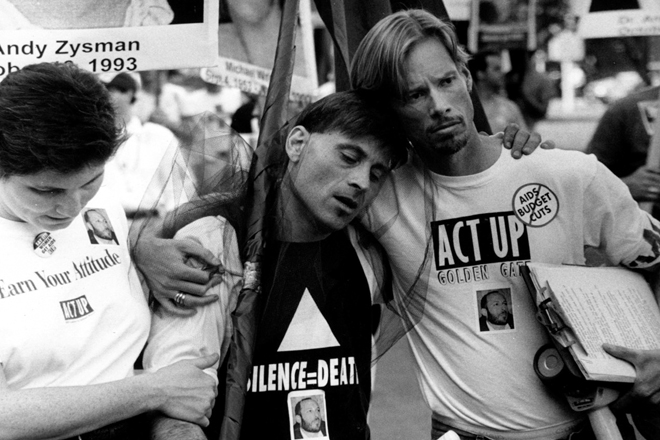

The AIDS epidemic hit San Francisco’s gay community in the early ’80s like a mysterious plague, killing thousands before anyone knew exactly what it was. It wasn’t that long ago, but the fear and devastation of those days may have been swept aside in the rushes for the cure and activism that’s followed, even as AIDS remains a worldwide pandemic.

That the horror of those days has been forgotten — or never learned — by younger generations inspired David Weissman’s “We Were Here,” an effective and moving documentary that revisits the harrowing era through the eyes of a handful of people who lived through it. Three decades later, they’re still trying to make sense of what happened.

The interview subjects are not famous or outspoken leaders in the cause, yet all of them — medical researcher Eileen Glutzer; Paul Boneberg, a director of a gay historical society; activist and educator Ed Wolf; florist Guy Clark and artist Daniel Goldstein — are thoughtful and compassionate.

“We Were Here” has received plaudits in film festivals but will receive its biggest one-time audience this week when it premieres on PBS’ “Independent Lens” (it loses four minutes for time considerations and parts of John Davis’ striking nude self-portraits had to be blurred).

We talked to Weissman over the phone this week about the work, its origins and its effects.

How did you come to make this film now?

The initial stimulus, the idea to make a movie, was something suggested to me by a younger boyfriend of mine named David Cohen. He had just heard me talk a lot about my experiences in those years and it sort of popped out in a conversation at one point. He said, “You know, you should really make a movie about this.”

Initially, I didn’t think that that was something that I really wanted to re-immerse myself in, but I realized pretty quickly that it was a story that had sort of disappeared and had never been told from the vantage point of the passage of time. Older people who had lived through it had sort of buried it and younger people just had no idea what had gone on in those years.

How did you decide to tell the story through the experiences of just five people?

I didn’t really know how I was going to tell the story initially. I knew I wanted to do it with clean, unadorned interviews. But I didn’t know how many people I’d have and I didn’t know exactly how I would pick them. So it wound up being a very intuitive process. In looking at it now, I was looking for people who were willing and able to really introspect on camera, to revisit painful stuff with kind of a fresh perspective and also people whom the audience would find affection and kinship for, to make a very difficult story more palatable.

I understand you have a Holocaust history in your own family. How did that inform your approach to the work?

Having a Holocaust background in my family, and just Holocaust awareness in general, made me aware there would come a time in which our community would need to tell its story and people would need to ask questions of us. As a pariah community, there’s an isolation. I think the same thing was true of Vietnam vets. There’s a reluctance to tell your story, and a reluctance to ask questions because there are social complications around just the identity of storytellers. So I think that even during the epidemic, I was aware that if any of us survived – which was not clear in the darkest years of AIDS – I think I was aware at that point that if we did survive there would come a time in which this history would need to be told both for the benefit of the people who lived through it as well as for the generations that needed to know.

The interview subjects are all especially articulate and thoughtful about what they’ve been through, each with considerable dignity.

That was part of the casting. I wanted people who had those qualities and really wanted to take this journey…

I don’t think anyone has told their stories in the way they’ve been given the opportunity to do so in this film. The unique experience of being interviewed is that you know the person you’re telling your stories to, someone who really wants to hear them, so it elicits different things than when you’re just having a conversation.

I moved to San Francisco in 1976. The movie very much parallels my personal experience … I think it’s a product of the fact that I lived through those same years, that the interviews became less subject/object interviews and more shared catharsis.

Another part of the story was the blind prejudice, or inaction officially. Was there less of that in San Francisco, or did you find that as well?

You have to remember that the Stonewall riots, which were considered the beginning of the modern gay liberation movement, was only 11 years before the first AIDS case showed up, so our movement was very young and very insecure politically as well as having our own insecurities. I think certainly there were many people who, because of their own religious background or whatever, also had that same self-doubt around, ‘Oh, is this because I’m gay that I’m getting this? Am I being punished for being gay?’

So we had our own homophobia and certainly the society was incredibly homophobic still. I think San Francisco probably was uniquely more open to its gay community, and the gay community here had a tremendous amount of political power. And I think that’s part of why the situation played out somewhat differently in San Francisco. We weren’t always having to battle against our own infrastructure, or our own media, which was very much the case in New York. And certainly, you get out of those major cities and it was only homophobia. So it certainly made things much more difficult; it made for tremendous government inaction, at best. But it also, on some level, contributed to a kind of unifying process because we knew that we were fighting for our life and no one was going to come to our assistance unless we really demanded what we deserved.

The movie is specifically about San Francisco, but I think it speaks to universal circumstances and themes. I think in times of crisis there are people who, for whatever reason, are able to and are motivated to rise to the occasion, and others find it very difficult – and I don’t say that with judgment.

I think it’s complicated to face a situation like the AIDS epidemic. It was a terrifying time and it was just very difficult. It was a combination of gay men, lesbians and friends and families and allies who came forward. But at the same time, many people’s friends and families abandoned them, their doctors abandoned them, the government abandoned them. So it was a mixed history of heroism and incredible homophobic cruelty.

It’s a very compelling and human moment, when one of the subjects, Daniel, says he did as much as he could, but sometimes it was too much.

For all of us who lived through it, like Daniel, when you hear him say there were times when he reached his limits — he did so much and he gave so much, so many people did. But there were times when you couldn’t take another sick person. You couldn’t take on another obligation. You couldn’t go to a hospital another time. You didn’t even want to know that someone was sick, because it just meant reengaging again with just extraordinary pain, and I think a lot of people feel residual guilt for the things that they weren’t able to do. And that’s a shame, because it was a very challenging time and I don’t think anybody is served by feeling guilt.

What are some of the reactions you’ve had from theatrical showings of “We Were Here” to date?

It’s been remarkable. The movie’s played in many, many different contexts. It’s even played the last two months on Virgin Atlantic. And I heard from a straight guy who said he stumbled upon it; he watched it on his flight from somewhere in the East Coast to Europe and he liked it so much that he watched it a second time coming back. These are the things that I didn’t anticipate in making the movie. I think people are finding it, depending on their vantage point, they’re finding it cathartic, they’re finding it inspiring, obviously there’s a tremendous amount of sadness that it evokes but ultimately it’s a story of love and compassion and people rising to the occasion. And also, it’s a testament to the power of community. So I think it’s a story that’s inherently deeply sad and tragic, but one that’s been serving to really leave audiences feeling unexpectedly uplifted.

How does “We Were Here” fit into the current context of gay politics?

For better or for worse, AIDS is the biggest piece of gay history since Stonewall. It started in 1981; it’s still going on. But the 15, 16 years when there was this enormous death rate in the gay community from AIDS. It’s the biggest piece of our history since liberation. It certainly has shaped our politics, it’s shaped who we are, I think that it forced so many people out of the closet, it forced families to acknowledge that they had gay people in their families, that their priest had a gay son or a lesbian daughter, it brought lesbians and gay men into closer working proximity. So I think it’s impossible to deny that those years of the most intense activity around the AIDS epidemic really altered both our own sense of politics within the community and the perception of us from the outside.

Is there a danger that putting the era in a historical perspective will make people think AIDS is a thing of the past?

We’re in a genuinely complicated situation. AIDS is every bit as dangerous as it was 30 years ago, if you don’t have medication. It’s not as if the disease has disappeared, just that there are medications that some people have better access to than others, that make it, at least for the moment, a manageable condition, which is a wonderful, wonderful thing. But it makes it more complicated to maintain a sense of urgency around prevention. It just has become a more complicated situation. And certainly, in some parts of the world, it’s every bit as bad as it was because of access to healthcare.

“We Were Here” premieres on “Independent Lens” on PBS, in most markets airing Thursday at 10 p.m. Check local listings.