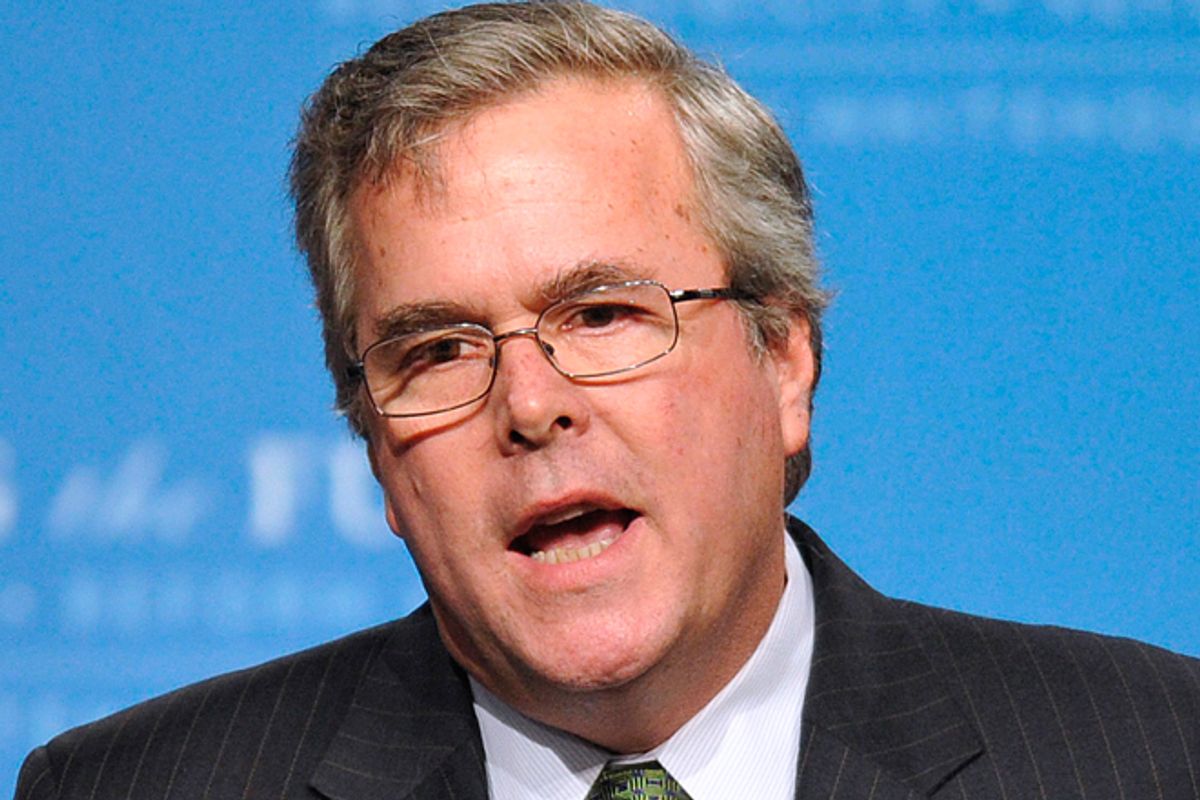

On first inspection, it might seem like Jeb Bush is trying to erase his name from the list of future Republican presidential prospects.

The former Florida governor told reporters in New York this morning that there probably wouldn’t be room in the Obama-era GOP for the party’s patron saint.

"Ronald Reagan would have, based on his record of finding accommodation, finding some degree of common ground, as would my dad — they would have a hard time if you define the Republican Party — and I don’t — as having an orthodoxy that doesn’t allow for disagreement, doesn’t allow for finding some common ground,” Bush said.

He also praised the tax hike deal that his father cut with Democrats in 1990 (a deal that spurred a Newt Gingrich-led conservative revolt and established the rigid anti-tax mind-set that now grips the GOP) and distanced himself from the party’s current hard-right immigration posture. This comes a few days after Bush told CBS News that the current race “was probably my time” if he was ever going to run for president and suggested that “there’s a window of opportunity, in life, and for all sorts of reasons.”

Add it all together and it sounds like the 59-year-old Bush might be coming to terms with never taking a shot at the White House. Or … he could be positioning himself to do exactly what his older brother George did a decade-and-a-half ago.

It’s hard to remember now, but in the wake of the 1996 presidential election – the last time a Democratic incumbent sought reelection – the assumption was that the 2000 Republican nomination would be wide open. For the first time in memory, there’d be no “next-in-line” heavyweight. Elizabeth Dole, fresh off her well-received Oprah impersonation at the GOP’s San Diego convention, was touted. Jack Kemp, a Reagan-era conservative hero who’d disappointed some on the right with his refusal to go on the attack as Bob Dole’s running mate, was in the mix. Dan Quayle was still around, Steve Forbes and Lamar Alexander were poised to run again, and John McCain seemed to have a national race in him too. And then there was George W. Bush, the popular governor of the second-biggest state in America.

Bush was easily reelected in Texas in 1998, then set out to run for president. The money and endorsements came in at an astonishing pace, and by the summer of 1999 Bush had become the most overwhelming primary season front-runner Republicans had ever seen. Why did this happen? The short answer is that Republicans decided they needed their own Bill Clinton.

It took them a long time to reach this point. When Clinton first came to office, Republicans resisted him with the same ferocity they’ve resisted Barack Obama since 2009. They challenged his legitimacy, killed his stimulus bill, voted unanimously against his 1993 budget, and derailed his “socialized medicine” healthcare plot. The resentment was intensely personal, too. When Clinton was scheduled to travel to North Carolina in 1994, then-Sen. Jesse Helms warned that “Mr. Clinton better watch out if he comes down here. He’d better have a bodyguard.” And when they scored an epic midterm landslide in ’94, Republicans took it as a validation of their approach: See, the public hates him as much as we do.

This is why the Gingrich-led Congress felt so confident forcing a budget confrontation with Clinton that led to the fall 1995 government shutdown. But Clinton welcomed the fight, positioning himself as the protector of a social safety net that rabid ideologues were out to destroy. There was genuine surprise on the right when Clinton “won” the standoff.

Then came the 1996 presidential race. In the wake of the ’94 midterms, the only suspense seemed to be over what the exact margin of Clinton’s reelection defeat would be. But by the time Dole emerged as the GOP’s nominee, the race was over. The economy was strong, Clinton’s popularity was healthy, and his polling leads were massive – and stayed so right up to the election, which he won by 8 points. As his approval rating soared in his second term, Republicans were more willing to deal with Clinton, although it wasn’t until after the 1998 midterms – when their impeachment drive backfired and produced Democratic gains – that the reality of how badly Clinton had beaten them sunk in with Republicans.

It was in this moment that they turned to the “if you can’t beat him, mimic him” strategy. After eight years of Democratic rule, Republicans just wanted to win the White House again. A major reason for Clinton’s success, they concluded, was how easily he’d been able to paint the congressional GOP as heartless, cruel and extreme. Bush, with his warm, affable nature and “compassionate conservatism,” was exactly the man they were looking for. He had built-in name recognition, a good resume (at least after the age of 40), and had built inroads with conservatives that his father had never managed to. He was the definition of a consensus candidate, and save for a few weeks of panic after the New Hampshire primary, his nomination was never in doubt from the summer of ’99 on.

Jeb may be thinking ahead to a similar moment. To this point, Republicans have only been rewarded for their unyielding opposition to Obama. But if he runs against their obstructionism and their economic priorities and ends up winning in November in the face of an awful economy? Maybe it would produce the kind of pragmatic reckoning that made Republicans receptive to W.

Obama himself seems to be anticipating such a moment, arguing recently that “when we're successful in this election, that the fever may break, because there's a tradition in the Republican Party of more common sense than that.” Of course, the GOP’s current obsession with ideological purity is also a product of the right’s belief that W’s presidency is a case study in the evils of big government conservatism. So it could be that, unlike 16 years ago, a loss in 2012 will only embolden the GOP to push further to the right, in which case there really will be no room for Jeb.

Shares