WASHINGTON — Shannon Hader knew from the start that this city had a lot to learn from Africa about how to confront an AIDS epidemic.

And when Hader told fellow AIDS experts in 2007 that she was leaving her prestigious post with the federal government to take on the local epidemic in Washington, D.C., nearly all of her colleagues told her it was an impossible task.

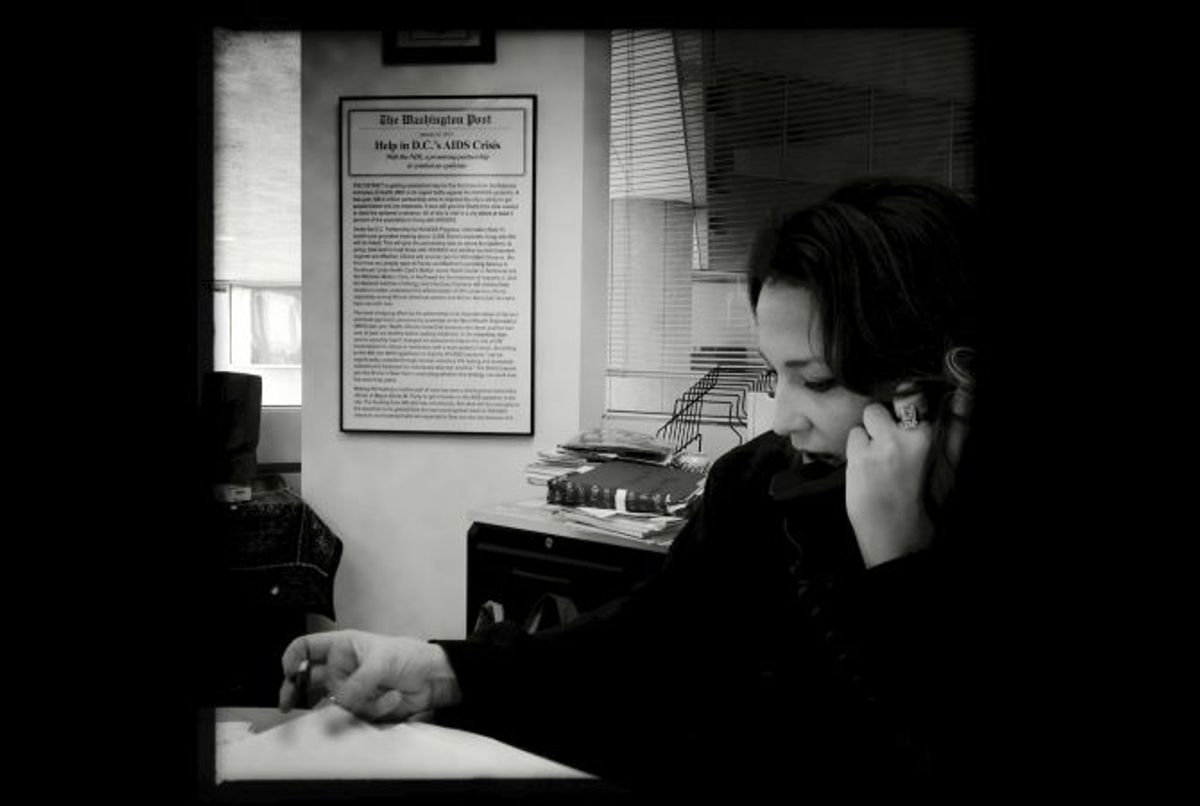

“People in the know were like, ‘That’s such a stupid thing to do. You can never make a difference,’” recalled Hader during a recent interview.

She was the city’s 15th director in 21 years. City government — often disorganized, sometimes plagued with corruption — had gathered almost no data on the epidemic in over five years.

Fresh off a tour as Centers for Disease Control country director in Zimbabwe, Hader saw firsthand how a streamlined approach, coordinating private and public entities, gathering data, and accountable programming could produce efficiency and change. It was an approach she intended on applying to D.C.’s chaos.

Her numbers-based approach and talk of lessons from Africa were met with mixed reviews. Some were offended by the comparison to Africa.

“Some people would say they really didn’t like Shannon,” said A. Toni Young, one of the city’s leading community organizers, based in Ward 7 — just east of Anacostia, the worst-hit area of the city.

Comparing Washington, D.C.’s 3 percent HIV prevalence rate to Africa was a sensitive one to locals — especially after new numbers told that some pockets of the city, like historically black Anacostia, had rates higher than Rwanda and Ethiopia. Hader’s frequent narratives about success in Zimbabwe heightened a sense that she was out of touch with the D.C. populace. That, and the fact that changing the way things worked for decades was not a pill people wanted to swallow. Hader’s new science-based strategy meant those not producing measurable outcomes would not be getting funds — hardly the emotional decision-making of her predecessors.

“If you’re looking for a hug, don’t call her,” said Young. “But if you wanted to get it done, that’s the lady to call.”

Still, some tough love may have been just what Washington, D.C., needed.

During her time in office, publicly supported HIV tests nearly tripled from 42,000 to 110,000. In 2009, the Department of Health reported the first ever decline in new AIDS cases. A year later, the department noted a preliminary decline in the number of new HIV and AIDS cases by nearly half from 1,311 in 2007 to 755 in 2009. And the number of deaths among persons with HIV/AIDS decreased by more than half from 326 in 2005 to 153 in 2009.

Inter-departmental politics ultimately drove Hader to leave her position in mid-2010, she said, much to the displeasure of locals proud of their new strides.

Email correspondences with Hader these days generally open and close with a “ciao” — an apt greeting for a woman who is regularly on transatlantic flights to countries like Kenya and South Africa, where she continues her AIDS and global health work with the Futures Group, also based in Washington.

Hader stays in touch with many of her local partners. She is proud of their success, but acknowledges their journey has only just begun.

GlobalPost's reporting on global heath is made possible in part through a partnership with the Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation as part of its U.S. Global Health Policy program.

Shares