New York City has a serious problem. Its problem is how it treats black and Latino males -- especially black and Latino males of the hiphop era. You have to wonder if the city actually wants us here. If so, why did the New York Police Department, in 2011, stop, question and frisk a record-breaking 684,330 black and Latino males, with 41 percent of those stop-and-frisks being youth between the ages of 14 and 24?

To understand this total of 684,330 -- an increase of 14 percent from the 2010 figure --think of it like this: The number of black and Latino males detained by the NYPD in 2011 is more people than the total populations of North Dakota (672,591), Vermont (625,741), Wyoming (563,626), or America’s capital, Washington, DC (601,723). Taken together, these detainees would constitute America’s 19th largest city, nestled between Detroit, Michigan (717,777) and El Paso, Texas (649,121).

Of those stopped last year, 92 percent were male and 87 percent were African American or Latino. In essence, we are demonizing and criminalizing an entire generation of black and Latino teen boys and young men—many of them already mired in poverty, sub-par schools, and limited employment possibilities—for the rest of their lives. And before they even know what hit them. This is not just a New York problem. This is an American epidemic, a national crisis, where it has become acceptable for local police forces to view black and Latino males in inner cities as menaces to society, first, and as citizens, maybe.

Take the case of Kenton, a young man in his early 20s, freshly arrived in New York City a few years back, and living in the Crown Heights section of Brooklyn. Like many black and Latino males in our great metropolis, Kenton is woefully undereducated, and consequently, underemployed. But he is a good young man, the nephew of a close friend of mine. In between odd jobs, Kenton would sit on the stoop when it was warm outside, taking in his very new environment. He does not use nor sell drugs, is not engaged in any criminal activity whatsoever. He is simply a young black man in America, and apparently, for some police officers, that is a crime in and of itself.

Almost immediately after his arrival in the ‘hood Kenton was repeatedly stopped and frisked by New York police officers. He was patted down in his building corridor, on his building’s stoop, and on the sidewalk. Baffled, Kenton would ask the officers, in his faint Trinidad accent, what was going on. Then what has happened to countless black and Latino males, including me when I was a much younger man, happened to Kenton: he was beaten by members of the New York Police Department. To add insult to injury, he was charged with resisting arrest (I’ve experienced that one, too), and found himself in a jail cell at Rikers Island. His leg was badly hurt by the vicious act of police brutality and he walked with a cane and limp for several months, as he shuffled back and forth to court in an attempt to clear his name and record.

I wish this story was an isolated incident, something that rarely happens in our New York City, in our America. Tragically, it is not. We know that those 684,330 street stops in 2011 represent a more than 600 percent increase since Mayor Bloomberg’s first year in office, when officers conducted 97,000 stops. In fact, more than 4 million people have been stopped under this administration’s watch.

The official line from Mayor Bloomberg and Police Commissioner Ray Kelly is that stop-and-frisk is necessary to halt the out-of-control violence in New York’s roughest neighborhoods. Well, I live and work as a community leader across the five boroughs, including in my home borough of Brooklyn, and I can tell you, without hesitation, that violence in New York City is higher than ever, whether the violence is being reported or not. Stop-and-frisk has done little to curtail that; instead, it has succeeded in marginalizing yet another generation of young males of color, while habitually contributing to the bad feelings between the black and Latino communities and the New York Police Department.

Statistics reveal that nine out of 10 individuals who are stopped and frisked are never ticketed or arrested. Though by law, police must have “reasonable suspicion” that a target is carrying a weapon in order to frisk them, no gun is retrieved in over 90 percent of the stops. The proportion of gun seizures to stops has fallen significantly—only 780 guns were confiscated last year, not much more than the 604 guns seized in 2003, when officers made 160,851 stops.

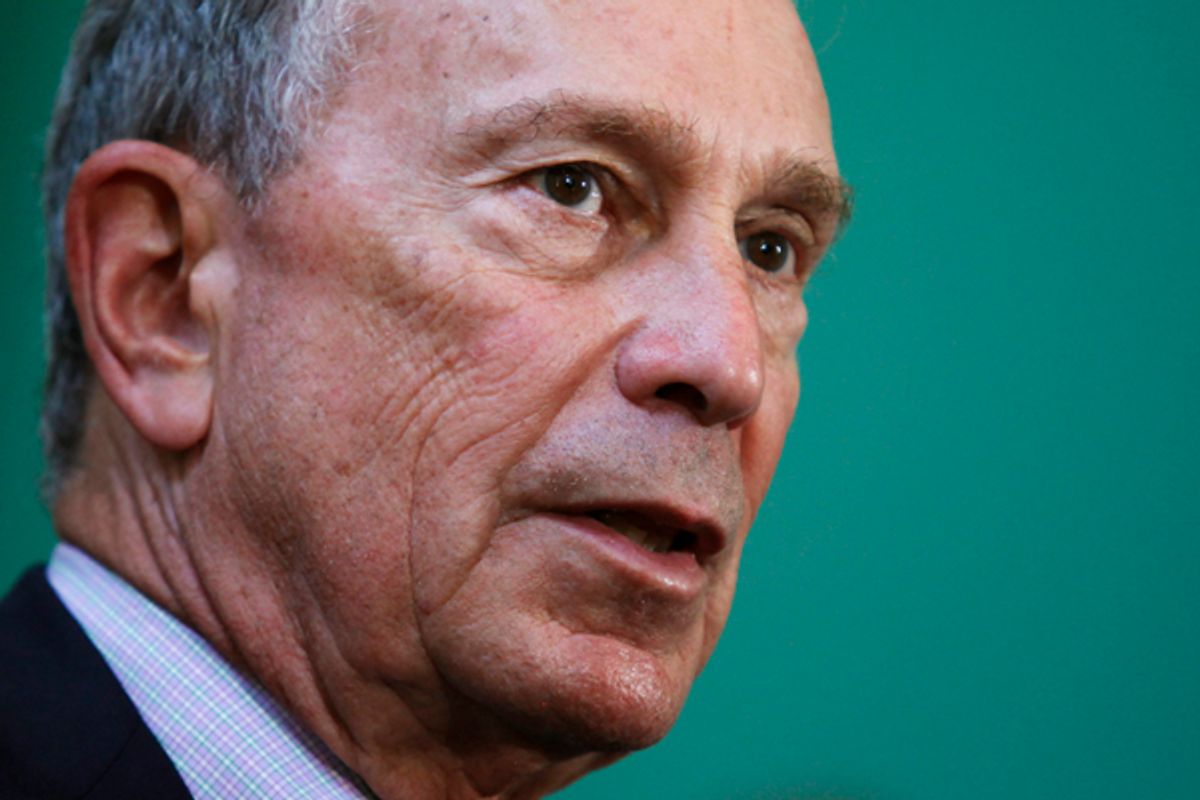

That is why it was so shocking and disrespectful for Mayor Bloomberg to show up, this past Sunday, at the First Baptist Full Gospel Church in the Brownsville section of Brooklyn (one of New York City’s poorest and most underdeveloped communities) to defend the city’s policy of stop-and-frisk. Shocking because the numbers do not lie and it was a week before the massive anti-stop-and-frisk silent march scheduled for this Sunday, Father’s Day, organized by a multicultural army of labor leaders, civil rights organizations, elected officials, and many others.

True to his form as an elite businessman who has always been out of touch with the masses of people in New York, the mayor stood before the congregation with an aloofness that has become his trademark. First he referenced Dr. King’s historic “I Have a Dream” speech and suggested that gun violence remained a barrier to racial equality in America.

No, Mr. Mayor. Wrong. As a product of the American ghetto the mayor clearly knows nothing about, I feel qualified to tell you that horrific public schools, limited employment opportunities, underdevelopment and gentrification, and the greed of those who prey on the misery and ignorance of poor communities in our nation are the real barriers to racial and economic equality. Guns and gun violence are merely a symptom of a larger problem: a pervasive sense of utter hopelessness, desperation, rage, and, yes, life-long pain caused by our circumstances.

But then Mayor Bloomberg took things a step further and announced that stop-and-frisk would not end. “I believe the practice needs to be mended, not ended,” he said, sampling President Bill Clinton’s words from a 1995 speech about affirmative action.

I will not say that Mayor Michael Bloomberg is a racist. I do not know the man and do not know what is in his heart. What I will say is that it was incredibly arrogant for him to stand in the heart of “black Brooklyn,” in a black church on a Sunday, no less, and toss into black churchgoers' faces Dr. King’s words, and then justify a practice that is not only inhumane, but also racist in its application.

There is no doubt that many of our people have had enough. This Sunday, Father’s Day, we expect over 50,000 people to show up for the silent march to call an end to New York City’s stop-and-frisk policy. The tactic of the silent march was first used in 1917, on the heels of World War I, when black soldiers who had fought gallantly for America returned home and were attacked by white Americans, just because. The NAACP organized this first silent march to draw attention to race riots that tore through communities nationwide, and to build mass opposition to lynchings.

Here we are, nearly 100 years later, in an America with its first black president and the kind of racial progress we could not have imagined 100 years ago. Indeed, what is so beautiful and powerful about this Sunday’s silent march in protest of stop-and-frisk is the fact that it has been put together by a progressive, multicultural coalition – groups and individuals who have united to say "Enough" to how we treat certain people in our society.

I have been deeply moved by white allies who’ve sent email after email, pledging their solidarity in this cause. This is not a black issue, or a Latino issue, or a male issue or a hiphop issue, it is a human issue. And until all of us mobilize -- as sisters and brothers, as a people concerned about the dignity and humanity of each and every one of us -- out-of-touch leaders like Mayor Michael Bloomberg will continue to believe they can defend ugly practices like stop-and-frisk.

Shares