Kate Summerscale's books are a balm to the wary narrative nonfiction reader, proof that not every good true story rests on a foundation of tweaked facts. This popular historian marinates herself in intensive research, but she doesn't show off. If the real-life characters she's writing about are passing a season in the French port town of Boulogne, then, with the grace of a novelist, she'll sketch in the atmosphere of the town, from the hillside park their house overlooked to the sidewalks full of expatriate English children tended by French nannies. That bit of scene-setting may be no more than a paragraph, but flip back to the notes, and you'll learn that she scoured three or four books to find those evocative details.

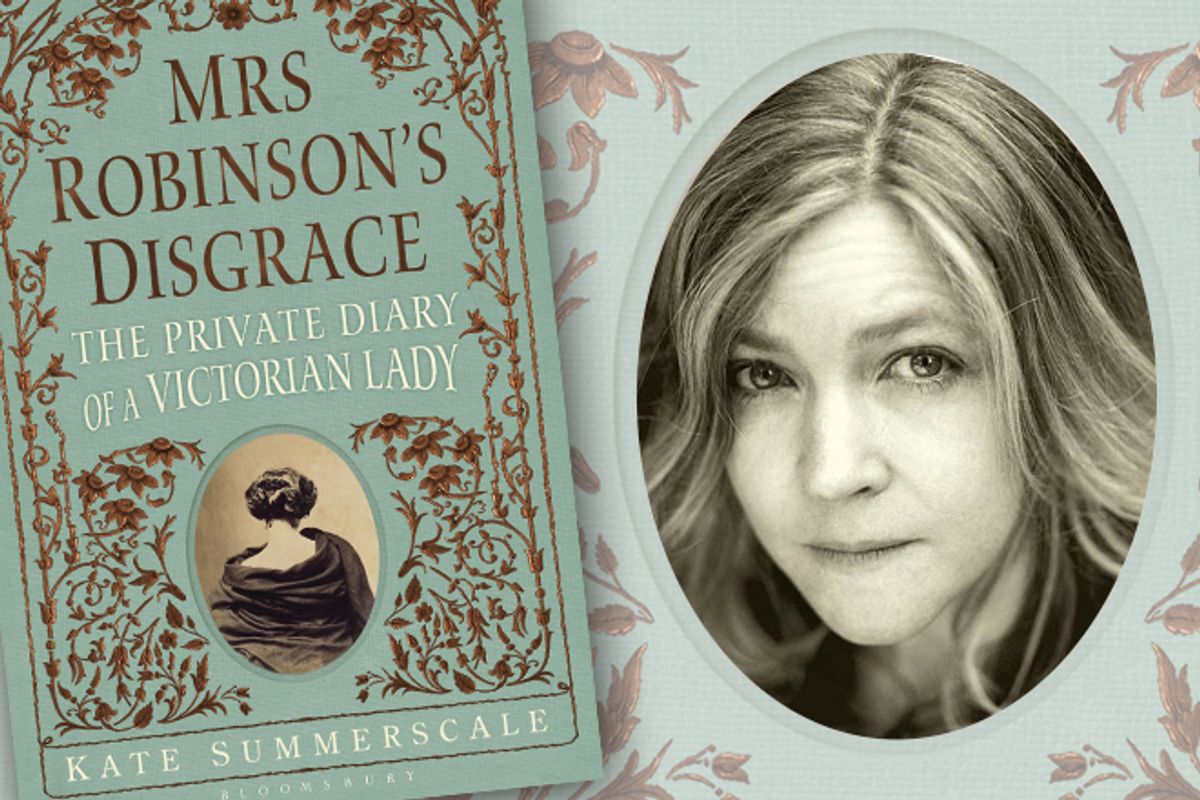

Summerscale had a critical and commercial success with her previous book, "The Suspicions of Mr. Whicher"; it was both an account of a murder in a 19th-century British country house and a history of the first police detectives. Her new book, "Mrs. Robinson's Disgrace: The Private Diary of a Victorian Lady," has a less sensational subject, but one on which feelings tend to run just as high: divorce. It's the story of one of the first modern divorce cases in Britain, and like "The Suspicions of Mr. Whicher," it resonates with the literature of its time, specifically Gustave Flaubert's "Madame Bovary."

Isabella Dansey was a 31-year-old widow with a young son when, against her better judgment, she married industrialist Henry Robinson in 1844. In 1858, Henry sued Isabella for divorce under the new Matrimonial Causes Act of 1857, which made divorce accessible to middle-class Britons for the first time. The chief item of evidence in the case was Isabella's diary, read by Henry while its author lay delirious in bed with a fever. In it, she detailed the misery of her marriage and her passionate infatuations with a series of young men, most particularly Edward Lane, a married doctor who was a friend of the family. Several of the entries involving Lane strongly suggested that her love for him had been consummated.

In "The Suspicions of Mr. Whicher," Summerscale used a police investigation as a crowbar to pry open the inner workings of Victorian domestic life, in particular the often-occluded power dynamics between classes and family members. With "Mrs. Robinson's Disgrace," she extracts what fragments of Isabella Robinson's diary survive in court records and newspaper reports (the original was destroyed) to bring us the unmediated voice of a genteel adulteress -- if indeed she was an adulteress. Isabella was the sort of woman whom the period's literature invariably depicted as a ruined, degraded, desperate wretch. Like Emma Bovary, unfaithful wives in the fiction of that era usually ended up dead.

What the magistrates and other observers found most confounding about the case was the diary itself, which even her own lawyer described as "monstrous." Charles Darwin, who was a patient of Lane's, marveled at "the unparalleled fact of a woman detailing her own adultery, which seems to me more improbable than inventing a story prompted by extreme sensuality or hallucination." Infidelity was simply the worst transgression a woman in Isabella's position could commit, as well as a literal crime. That she would want to make a written record of it was unthinkable.

To protect Lane, Isabella agreed to present herself -- both to their mutual friends and in the courtroom via her attorney -- as delusional and/or insane, a nymphomaniac or erotomane (or both), two categories of pathology Victorians assigned to women who desired sex with men other than their husbands. Her diary, according to this argument, consisted of accurate accounts of everyday events infused with -- and occasionally taken over by -- fantasies of a romance with the handsome and cultured doctor. Everyone in her circle agreed that Isabella was a woman of, as Lane himself put it, "considerable literary attainments," as well as an avid reader. Many of Lane's friends preferred to view the diary as the result of an imagination inflamed by too much sentimental literature, as well as a sort of private novel, create by its author for her own reading pleasure.

It's difficult to judge from the diary excerpts Summerscale has retrieved just how far things went between Isabella and Lane. Their contemporaries regarded the diary as extremely indecent and racy; ladies were banned from the courtroom more than once when excerpts from it were being read. To a contemporary reader, it's the self-portrait of a woman of strong moods and frustrated emotional and intellectual longings, trapped in a relationship with a man who gave every sign of having married her for her money. (She always maintained that he was rifling her writing desk for cash when he discovered the diary.) The word Isabella most often used to describe her husband was "narrow," but the record also suggests that he was vindictive; he once sued his own brother, and his desire for revenge was so strong that he pursued his suit against Lane and his wife to the point that his own reputation was damaged.

Even more flabbergasting to the contemporary reader is the fact that Henry himself openly kept a mistress, with whom he had two illegitimate daughters. While keeping the two sons he had with Isabella apart from their "immoral" mother, he even installed one of these girls under the same roof with them. Under Victorian law, a man could divorce a woman for infidelity alone, but a woman had to prove her husband guilty of two out of three marital crimes: adultery, desertion and cruelty. Summerscale, who mostly refrains from editorializing on these and other aspects of 19th-century gender relations, imparts these facts and leaves them to kindle a slow burn in her reader.

It was, furthermore, the case that Henry owned all of Isabella's writings; the product of a wife's labor belonged to her husband. "The copyrights of my works are his," wrote the 19th-century author and feminist reformer Caroline Norton about her wastrel spouse, "my very soul and brains are not my own." Unlike Norton's husband, Isabella's did not want to profit from her writing (it was about the only thing of hers he didn't try to profit from), but he did want to eradicate her voice by turning it into a source of unspeakable shame. Thanks to Summerscale, he failed. In "Mrs. Robinson's Disgrace," at last, she comes through loud and clear.

Shares