Jill Lepore's mind doesn't work in an especially strange way; anyone who's ever done intensive research knows what it's like to reach the point where every fact, every life story, every curiosity in your findings seems miraculously linked to everything else in a vast, gorgeous web. History becomes a single, uninterrupted tissue instead of a collection of separate narrative strands. The unusual thing about Lepore's work -- she writes about American history and culture for the New Yorker -- is that she aims to reproduce that sensation of uncanny connectedness in her reader. It shouldn't work. There should no more be a shortcut to the ecstasy of the researcher than there is to the serenity of meditator. But, strangest of all, Lepore pulls it off.

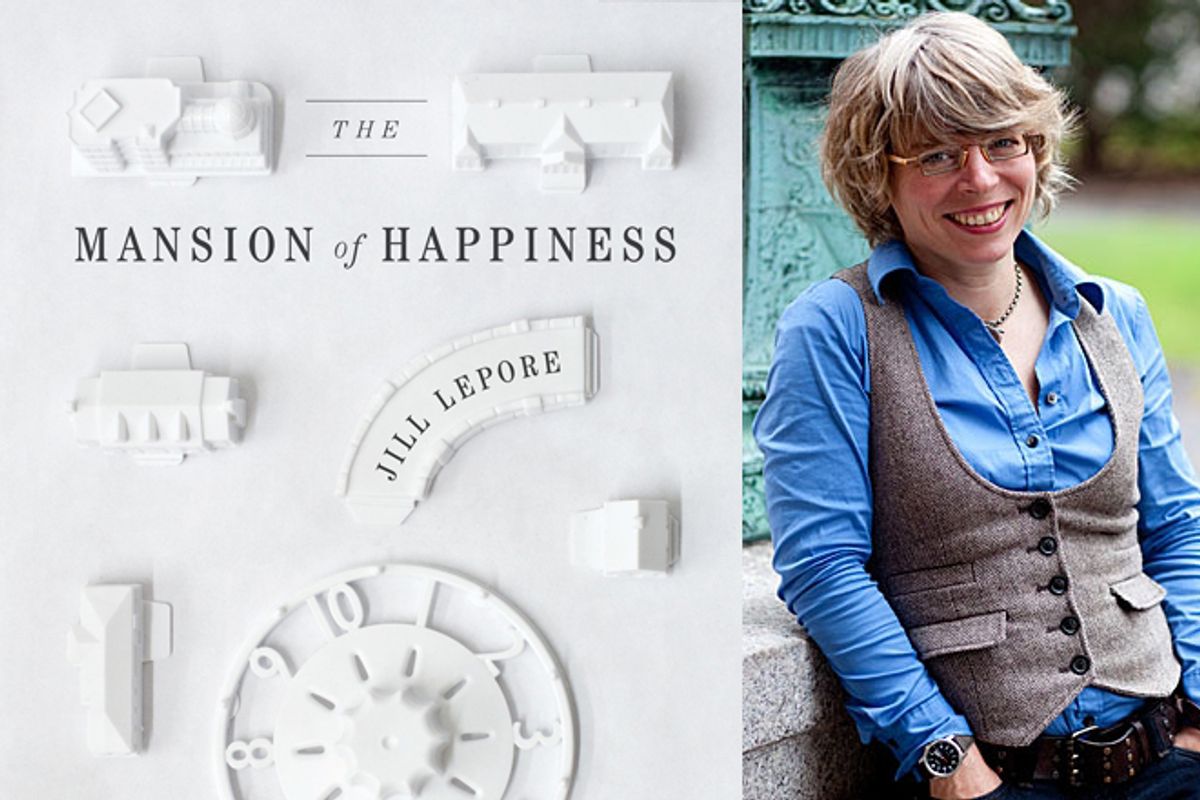

Lepore's new book, "The Mansion of Happiness: A History of Life and Death," is militantly low concept. It's hard to sum up in a neat thesis, but a line from her final chapter, the last of 10 about how we view the stages of life and death, comes fairly close. It concerns cryonics, the freezing of human corpses (or sometimes just the head) in the hope that the future technology can restore the dead to life. Cryonics, Lepore writes, "is what happens when ideas about life and death move from the library to laboratory, from the humanities to the sciences, from the past to the future, and get stuck there."

She thinks Americans are stuck there, have traded in our faith in both God and humanism for an investment in science as the sole reliable authority on any question. It's not that Lepore doesn't appreciate science. She makes a point of nailing fake doctors -- from the popularizer of cryonics to the propounders of various quack theories on nutrition, sexuality and child-rearing -- people who either falsely assumed the credential or were blithely awarded it by the media. So she still thinks a Ph.D. or M.D. counts for something. But she also thinks we're kidding ourselves if we believe that those who have one are qualified to tell us how best to live or die.

One of the pleasures of Lepore's work is the way she uses a single, deftly chosen artifact to crack open a much wider cultural vista. Her introduction considers board games, specifically board games portraying the "game of life." The first of these was created as far back as 1790; the one you know about was designed by Milton Bradley in 1860. An intermediate variation, the Mansion of Happiness (from which this book takes its title), appeared around 1800. The Mansion of Happiness depicted life as a struggle to practice virtue and avoid vice, thus eluding the game's lurking antagonist: Satan. By the time Bradley produced his popular version, however, "you don't play against the devil; you play against other men. And you don't play for your soul; you play for success." When designers tried to update the Game of Life in the 1990s, they could not figure out a way to broaden its representation of life's rewards. Whenever the play became "less about having the most money," people found "it made no sense."

Some of the stories Lepore chooses to tell serve her purpose better than others'. Her account of how a single woman, Anne Carroll Moore, founded and ruled the world of American children's libraries during the first half of the 20th century, and of how Moore tried to keep E.B White's "Stuart Little" out of those libraries because it clashed with her fogeyish notions of what kids ought to read, is fascinating. It's also a pretty decent, if somewhat indirect, reflection on how attitudes toward childhood have changed. It hasn't got much to do with science, however, and it's one of the chapters in which the origins of this book as a bunch of miscellaneous New Yorker articles causes its unifying strand to fray.

On the other hand, there's brilliance in the way Lepore links the famous 1965 Life magazine photo spread "A Child Is Born," featuring images of developing fetuses, with Stanley Kubrick's "2001: A Space Odyssey," in which the main character in the film is transmuted into a fetus "floating through space, in an egg." The Life series, taken from a book of the same title by Lennart Nilsson -- the biggest-selling illustrated book of all time and literally launched into space aboard NASA's Voyager probes -- were supposed to depict living fetuses, when in fact they did not. (Nilsson photographed medical specimens.) Lepore considers both the photos and the film as fantasies of prenatal life with a crucial element removed. "Kubrick's '2001,'" she writes, "told the story of the origins of man -- without women." Nine chapters later, the filmmaker wanders back into "The Mansion of Happiness," when his obsession with cryonics crops up. He bought many copies of a book by "Dr." Robert Ettinger, whom Lepore profiles, to give to his friends. See? It's all connected!

Here, Lepore convinces, highlighting a futuristic sterility in both "2001" and "A Child Is Born" that can be provocatively, but fruitfully, linked to discomfort with women and their troublesome bodies. Not that Lepore comes out and states this, however, for the one nagging flaw in her own work is a propensity toward coyness. She mentions that White was living only 60 miles away from the lab of C.C. Little, a genetics researcher who pioneered the use of lab mice, when he gave his mouse, Stuart, a last name. Is she suggesting that the character was named after the scientist? Isn't it just as likely that it's a meaningless coincidence and White called him Stuart Little simply because he was little? If Lepore knows otherwise, why not say so? If not, why even mention it? This is meant to be playful, I know, but instead it's just irritatingly arch.

Still, such stumbling is relatively rare in "The Mansion of Happiness," and worth forgiving when you see how Lepore's friskiness enhances her marvelous profile of Ettinger, with his warehouse full of frozen people and cats. On the weightier side, there's a potent chapter on the now half-forgotten Karen Ann Quinlan trial (in which the parents of a comatose young woman petitioned for the right to turn off artificial life support) and the "fundamental shift in American political history" that it marked. This was the first medical "right to die" case, and it divided the nation in 1976. Lepore argues, persuasively, that the new and peculiarly American flavor of paranoia it signaled persists today in the hysteria over "death panels." The idea of medical science arbitrating the possibility of meaningful life was profoundly disruptive. Patients had fallen into a "persistent vegetative state" before, she points out, but they had always been quietly allowed to die. "What was new," she writes, "wasn't pulling the plug or not pulling the plug. What was new was the plug."

If the bonds between the disparate subjects and motifs in "The Mansion of Happiness" sometimes seem to be sustained by Lepore's own personal version of extraordinary measures, there are plenty that hold firm. They can't be disputed or endorsed like traditional historical theories, but they can dazzle and illuminate and inspire. And that's just what they do.

Shares