There is the thing. And things about the thing. Or, to dress that thought up, all proper-like, there is meta perspective, a post-ironic approach, or that old standby, the homage.

"The Artist" was a much-beloved phenomenon last year. An exquisitely crafted love letter to the lost Art of Silent Film, it levitated into the hearts of some audiences -- including just about all the critics and the ever-unreliable Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences. Why then, does it feel like such a chore to watch? And why do I feel guilty even thinking such a thing, let alone writing it? It’s like kicking the adorable Uggie the Dog.

Michel Hazanavicius approached this project with the most noble of intentions. To transport modern movie audiences back into time, by lovingly re-creating the vocabulary of the silent film. He succeeds totally in that department. But is this a round trip really worth taking? For "The Artist" seems like the master thesis of an absolutely brilliant film student, who really, really wants to impress the faculty on just how well he has done his homework. Hazanavicius has been candid on how he obsessively studied the silent film masters. Murnau’s "Sunrise" and "City Girl," and Chaplin’s "City Lights," were his textbooks, and it is clear that he read them well. Too well. There is the thing, and things about the thing.

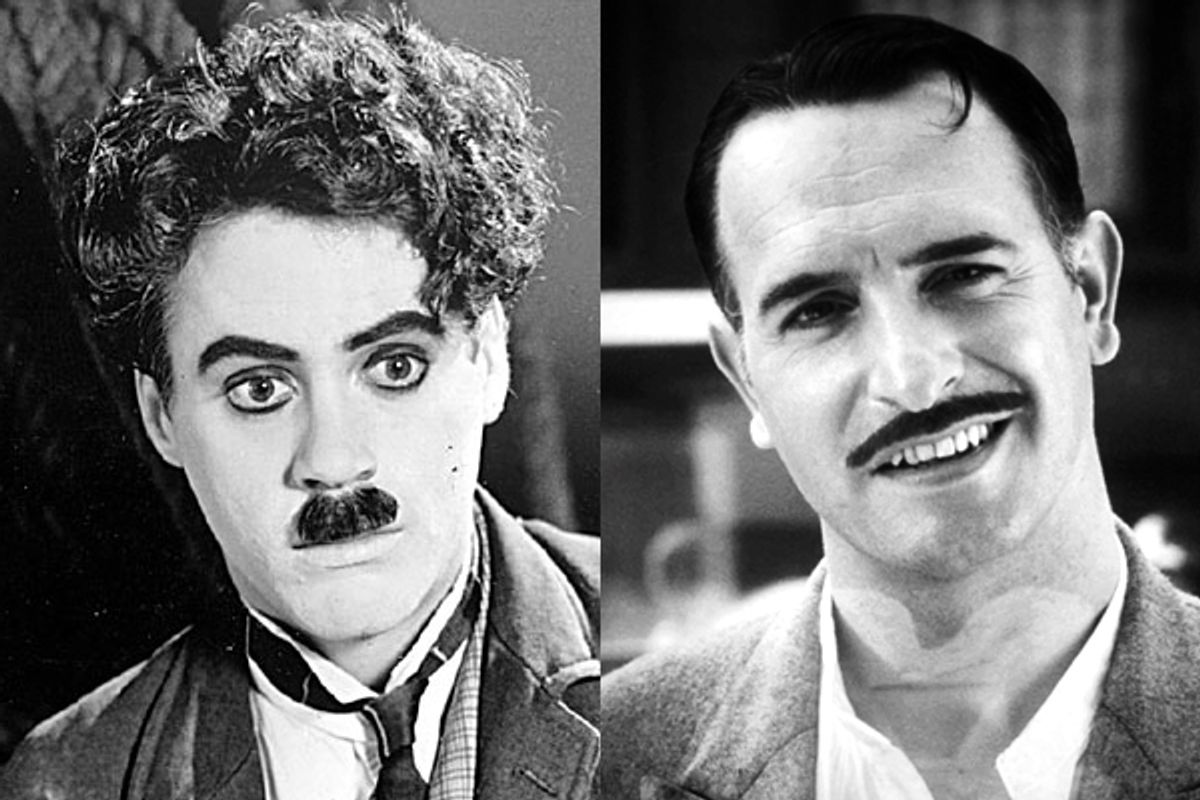

And "The Artist" is not the thing. First off, the casting is off by one major lead. Although Jean Dujardin brilliantly embodies that Douglas Fairbanks ideal of the insouciant silent film hero, the love interest is played by Hazanavicius’ wife, Bérénice Béjo. Always be suspicious of nepotism in casting. Although Béjo is radiant in the part, she is also about 15 years too old for the starry-eyed ingénue the role demands, and in a movie determined to get the details right, well, Béjo is no young Joan Crawford who was her particular role model for this endeavor. I don’t buy for a second any part of her performance, nor her performances within the performance. A gallery of gifted actors do parade through "The Artist," but are there for little more than stunt appeal. These include an inexplicable cameo from Malcolm McDowell, who seems to be cast only so we can say, hey, there’s Malcolm McDowell!! What’s he doing here? Well, not much.

But stunt casting aside, the worst thing about "The Artist" is that it is somehow grueling to watch -- even at a little over an hour and half. The joy of watching an old form made new wears off, and I found myself checking my watch waiting for the inevitable mechanics of the plot to kick in. And let’s face it, we’ve seen this Rise and Fall of Hollywood Star arc before, for better and for worse. And kick in they did, predictably. After one brilliantly surprising dream sequence, I thought I was watching another dream when Valentin’s shadow walked off the screen, heralding his Uggie-denied attempt at self-immolation. But then, I realized, this wasn’t the thing, nor the thing about the thing, it was a thing driving the plot about the thing. Yes, I’m weary, too, just writing that. But not nearly as weary as I was of "The Artist" by the time the credits finally rolled.

I was reminded of another love letter to the silent cinema that came out last year, that matched "The Artist's" numerical Academy Awards, in somewhat lesser categories. But Martin Scorsese’s "Hugo" didn’t just re-create the magic behind George Méliès protean works of imagination. In "Hugo," Scorsese used his personal magic to create new magic and a new vocabulary that defines 3-D filmmaking. When he applied that technology to re-create Méliès’ fantasias, there was a shock of recognition, of connection. You felt transported into seeing cinema for the first time – a journey that "The Artist" maps out – but never quite takes.

Now, I am sure Scorsese loved "The Artist." Anyone who cherishes film has to applaud its intentions and celebrate its success. But that’s different from it actually being anything other than a novelty – an embalmed novelty at that.

Now, when you think of “embalmed” filmmaking, it's hard not to reference the works of Richard Attenborough. From "Gandhi" to "A Bridge Too Far" to, gasp, "A Chorus Line," Attenborough is the Lean Cuisine David Lean. He’s always struck out on the road of good intentions, but never has quite reached his destination.

Which makes Robert Downey Jr.’s triumph in our Double Bill of "Chaplin" even more astounding. This soul-shifting portrayal is not only the thing, it transcends the thing – and is one of the most amazing performances of the last 25 years. Watching this again, I’m reminded and relieved about the cultural tragedies that didn’t happen. We lost Hendrix, but Dylan did walk away from that motorcycle accident. And the spiral of personal disintegration before and after "Chaplin" almost claimed Robert Downey. But luckily, we got him back.

In "Chaplin," Downey incarnates Chaplin, not only pulling off the pathos and the genius, but also the slapstick physical genius that lay at the heart of Chaplin’s art. Beautifully shot by Sven Nykvist, Downey is riveting in every single scene, despite being saddled by a Bio 101 screenplay and the ever noble intentions of Attenborough.

Just how good was Downey’s in "Chaplin"? So good that he lost the Oscar to Al Pacino’s insufferable “Hoo-ahh” performance in "Scent of a Woman."

No wonder Downey went back on drugs.

Jean Dujardin may have played a Douglas Fairbanks act-alike, but a shout-out here goes to Kevin Kline, who in "Chaplin" plays the real deal. Kline gets the Gene Hackman lifetime achievement “Good In Everything” Award (OK, there is "Marooned"), and this film is one of the many reasons why. For those playing at home, Penelope Anne Miller plays Edna Purviance in "Chaplin" with far more vividness than the way she plays the long-suffering wife of George Valentin in "The Artist." "Chaplin" is studded with other enjoyable cameos, as is Attenborough’s style. Dan Aykroyd is actually tolerable as Mack Sennett, and Diane Lane is wonderful as Chaplin’s muse Paulette Goddard.

Like "The Artist," "Chaplin" attempts to capture the lightning of silent filmmaking in a bottle. It veers off course many times, but occasionally it is spooky in its feel, especially in the early scenes of Hollywood shot in the still-verdant (last time I looked) hills and valley’s surrounding Fillmore, Calif. Hollywood was truly an orange-scented paradise, and no film has ever quite captured its rawness and aching potential as well as those formative scenes in "Chaplin." A time when anything was possible and an art form was being invented seems just in reach – and with Downey’s eerie performance as a siren, we are sucked into that lost world.

If "Chaplin" or "The Artist" does succeed in luring you back into the world of silents, perhaps the best next step is the "The Unknown Chaplin. This two-and-a-half-hour documentary, written and directed by Kevin Brownlow and David Gill, dissects Chaplin’s working methods by showing his outtakes – and this should have been a central text in Michel Hazanavicius’ silent film school. It remains one of the most illuminating documents of the artistic process in any medium, and is thankfully still available, unlike the criminally scarce Brownlow and Gill “Hollywood” series. That 13-hour Thames TV series, perhaps the definitive document of the Silent Era, remains in legal limbo, and its unavailability remains a tragedy for all film buffs. "The Unknown Chaplin" will have to suffice, for now. I remember seeing a theatrical screening of it at UCLA’s huge Royce Hall. Sitting in front of me was a little old lady. My seatmate clued me to her identity. She was Chaplin’s once-child bride, Lita Grey. Seeing "The Unknown Chaplin" through Lita’s eyes, as she watched her ex-husband at work, was one way of kicking open that time portal into the past.

Hazanavicius and Scorsese are both to be celebrated for also trying to usher audiences through that backdoor. But on the strength of the final product, only Robert Downey Jr. seems to have been able to make the trip necessary.

Shares