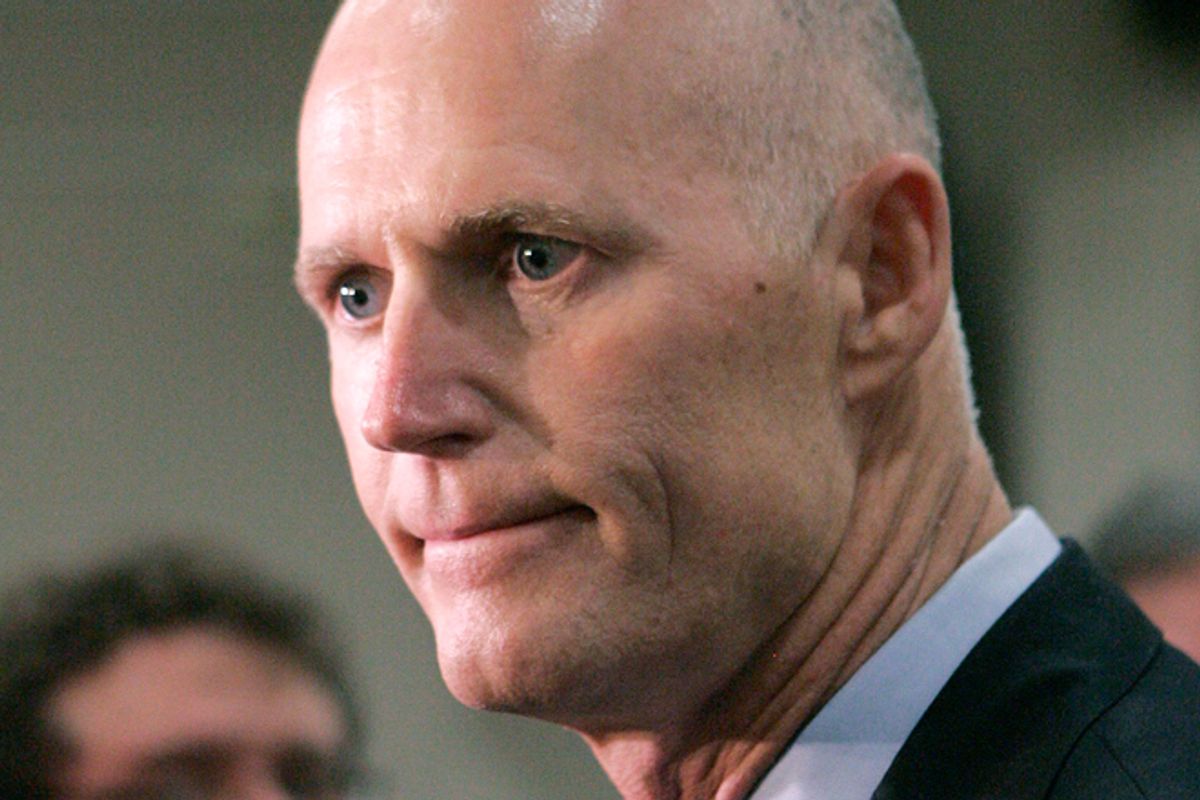

The Supreme Court struck down the provision in the Affordable Care Act that required states to accept an expansion of Medicaid coverage — presently available to unemployed parents who make, on average, less than 37 percent of the federal poverty level; henceforth to be raised to 133 percent of the poverty level — or lose all their Medicaid funds. Now Republican governors like Florida’s Rick Scott are deciding whether to reject the new Medicaid funding. Republican representatives are already urging their home-state governors to turn down the money.

Rep. Phil Gingrey of Georgia, when asked what the 500,000 people in his state who would thus be deprived of insurance are supposed to do, simply said that those at that income level have “got a little bit more money in their pocket than those who are at 100 percent of the federal poverty level.” A great comfort if they get cancer. (Gingrey actually misstates the preexisting rules in Georgia, where working parents are eligible only if their incomes do not exceed 50 percent of the poverty level, or about $9,500 for a family of three, while adults without dependent children are not eligible at any income level.)

I will here focus on the reasoning by which Chief Justice Roberts — and, by a different path, justices Scalia, Kennedy, Thomas and Alito — reached this result. Roberts would have federal courts decide, through some unspecified process, when a modification of an old program transforms it into a new one such that the Constitution forbids Congress from presenting the two as a take-it-or-leave-it package. The Scalia group suggested that a federal program becomes unconstitutional just by being big. These are extraordinary, nonsensical new rules that only make sense in light of a background assumption that government must be restrained by any means necessary. And that, in turn, depends on a strange conception of the liberty that the Court is trying to protect.

Begin with Roberts. He relied on earlier declarations by the Court that financial inducements would be impermissible if they are “so coercive as to pass the point at which ‘pressure turns into compulsion.’” This way of putting matters raises deep philosophical questions about what “coercion” is. Clearly I’m coercing you if I put a gun to your head. Threats are easy. But what sense is there in the idea of coercive offers? Maybe they make sense when Esau is so desperately hungry that he will give Jacob anything for some food. But Roberts thinks that there’s coercion any time I make an offer you surely won’t refuse. If I offer you a million dollars to take off your left shoe and put it back on, I can be pretty sure you’ll take my offer, but have I forced you? The difference is that in the gun case, you’ve got a right not to be harmed, but in the shoe case, you have no right to the cash if you keep your shoe on. As Scalia put it in another context, “The reason that denial of participation in a … subsidy scheme does not necessarily ‘infringe’ a fundamental right is that — unlike direct restriction or prohibition — such a denial does not, as a general rule, have any significant coercive effect.”

But Roberts declared that denial of future funding – funding that, more than a year or two down the road, has not even yet been appropriated by Congress – “is a gun to the head.” Because the program is so big, “over 10 percent of a State’s overall budget,” it “is economic dragooning that leaves the States with no real option but to acquiesce in the Medicaid expansion.”

In fact, states agreed, when they first took Medicaid funding, that Congress was free to modify the program in the future. And, as Justice Ginsburg made clear in her opinion, it has done that repeatedly. Roberts responds:

The Medicaid expansion, however, accomplishes a shift in kind, not merely degree. The original program was designed to cover medical services for four particular categories of the needy: the disabled, the blind, the elderly and needy families with dependent children. Previous amendments to Medicaid eligibility merely altered and expanded the boundaries of these categories. Under the Affordable Care Act, Medicaid is transformed into a program to meet the health care needs of the entire nonelderly population with income below 133 percent of the poverty level. It is no longer a program to care for the neediest among us, but rather an element of a comprehensive national plan to provide universal health insurance coverage.

The logic here turns crucially on the distinction between “the neediest among us” and “the entire nonelderly population with income below 133 percent of the poverty level.” Evidently Roberts thinks that if you’re merely at the bottom of the income scale, you are not one of the neediest among us. How does he know that? Three days earlier, dissenting from a decision invalidating mandatory life without parole for a teenager who participated in a robbery where someone was killed, he declared that the role of judges is not to answer “grave and challenging questions of morality and social policy.” But now, Roberts is sure that, as a constitutional matter, the guy who washes the dishes at the restaurant where Roberts eats his lunch, who perhaps is just above the poverty line, is not among the neediest. Rep. Gingrey is right: That fellow has a bit more money in his pocket. Medicaid has for years drawn the line on the basis of a judgment that if adults without children are too poor to pay for medical care, that is their own fault; it’s a fair consequence of free markets if the working poor die or are bankrupted by preventable diseases. Until now, this was a policy judgment, one that Congress felt free to, and did, reject in the ACA. Now it is a rule of constitutional law.

So where is the line to be drawn between inducement and coercion? Roberts does not give us a clue. “We have no need to fix a line ... It is enough for today that wherever that line may be, this statute is surely beyond it.” (The deepest mystery about the ACA decision is why justices Breyer and Kagan, who ought to know better, joined this part of the opinion.)

Now consider the Scalia group. They acknowledge that states are free to refuse money offered by Congress, but they note that “a contract is voidable if coerced.” (Relevance doubtful: A court would not thus void the contract in my shoe example.) They reject the government’s contention that “neither the amount of the offered federal funds nor the amount of the federal taxes extracted from the taxpayers of a State to pay for the program in question is relevant in determining whether there is impermissible coercion.” Why do they reject this claim? They explain:

This argument ignores reality. When a heavy federal tax is levied to support a federal program that offers large grants to the States, States may, as a practical matter, be unable to refuse to participate in the federal program and to substitute a state alternative. Even if a State believes that the federal program is ineffective and inefficient, withdrawal would likely force the State to impose a huge tax increase on its residents, and this new state tax would come on top of the federal taxes already paid by residents to support subsidies to participating States.

This has broader implications than they acknowledge. They have not just described the Medicaid expansion. They have described Medicaid itself. As they note, Medicaid is by far the largest federal program of grants to states. Its funding in 2010 exceeded $552 billion, approaching 22 percent of all state expenditures combined. The new restriction on the spending power would seem to mean that “the sheer size of this federal spending program in relation to state expenditures” makes it unconstitutional because “a State would be very hard pressed to compensate for the loss of federal funds by cutting other spending or raising additional revenue.” There is also a hint that federal taxation itself might violate the Constitution if it is excessive because “heavy federal taxation diminishes the practical ability of States to collect their own taxes.” (They don’t mention the sixteenth amendment, which on its face gives Congress unlimited power to raise any taxes it sees fit.) It is not clear whether they are serious about these wild new rules. A determination to trash the ACA evidently overwhelmed normal considerations of judicial craftsmanship and clarity.

What will the Court’s decision do to the people who are affected by it? Consider Texas, where one in four residents is uninsured, the highest rate in the country. Adults who are not disabled or elderly can get Medicaid there only if they have children, and then only if their incomes are below 23 percent of the poverty level. The ACA adds nearly 2 million people to the Texas Medicaid rolls – or was going to, before the Supreme Court stepped in. Now state officials are trying to decide what to do. You might think that Gov. Rick Perry couldn’t possibly be brutal enough to deny insurance to that many people, when it is free for the state in the first few years and later has the Federal government picking up 90 percent of the tab. If you think that, you don’t know Rick Perry very well.

A grim irony is that the Medicaid funds are most likely to be refused in poor states like Georgia and Texas, where they are most urgently needed. They won’t be passed up by New York or California. (Thanks to Bill Eskridge for pointing this out in conversation.)

Roberts says that without these new spending power limitations, “individual liberty would suffer.” He doesn’t say how. Evidently, there are suppressed premises in his reasoning. But we can offer an educated guess about what these are.

What is really at war here is different conceptions of individual liberty. I always thought that liberty meant the ability to live one’s own life as one likes without being pushed around by others or suffering desperate deprivation. On that understanding, basic health, undergirded by medical care when necessary, is just part of the liberty that ought to be guaranteed to everyone. The ACA is a step forward for freedom. But there is another view, which holds that individual liberty just means limitations of government power. That means that it’s your tough luck if you’re sick and can’t pay for it: Your situation isn’t a threat to your liberty or anyone else’s because government isn’t causing it. This Tough Luck Libertarianism evidently is the caulk that is filling the huge gaps in these judges’ reasoning.

Shares