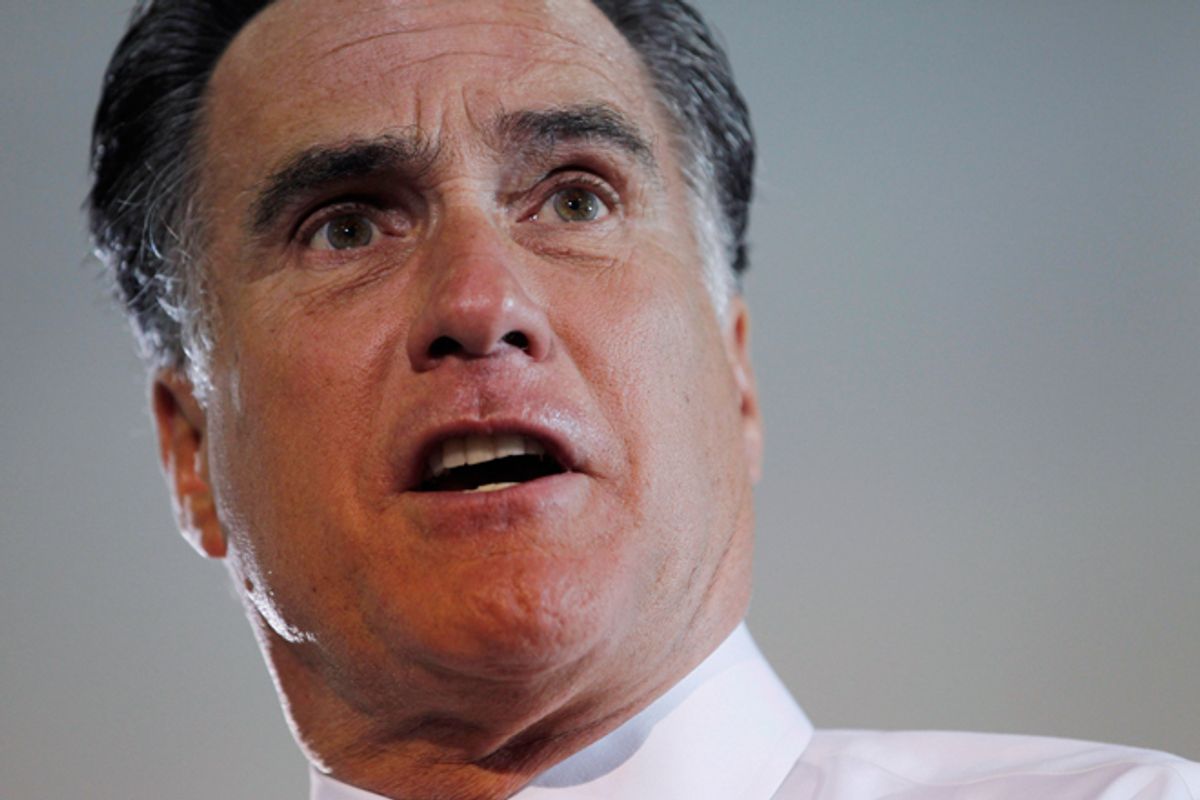

While new campaign finance vehicles created in the wake of the Supreme Court’s Citizens United deal, like super PACs, have gotten a lot of attention this year, there have long been ways for corporate donors to skirt campaign finance limits. In 2004, then-Massachusetts Gov. Mitt Romney found one such way to allow his network of wealthy corporate donors to give far more than state law allowed in direct contributions to state legislative candidates.

In a move that has gone largely unnoticed during Romney’s 2012 presidential bid, Romney and his aides solicited money from deep-pocketed donors and funneled it to Republican candidates via two state party funds, “sidestepping the cap that limits an individual donation to a candidate to $500 a year,” the Boston Globe reported at the time. Romney’s scheme allowed an individual donor to contribute $15,000, 30 times the typical $500 maximum. The money passed through two party committees, one of which was a federal account run by the state GOP that could take $10,000 from each donor. The other was a state account, which could take $5,000.

The plan was part of Romney’s larger effort to revive the ailing Republican Party in the state, and involved the governor personally recruiting GOP candidates, who were then supported with state party funds from these two committees for which Romney fundraised. Thanks to his network of financial industry and other donors, by September, Republicans had pulled in huge sums from large corporations in the state. The Globe reported that Fidelity Investments, one of the state’s largest employers, which regularly lobbies the state government on tax and other issues, had donated $203,000. Officials from Bain Capital, Romney’s former company, had given $92,000. In total, nearly $500,000 came from venture capitalists, while another $338,000 came from the financial industry.

The Globe reported that campaign finance advocates “argue[d] that Romney and the GOP are breaking down the legal barriers that bar corporate money from being used in state political campaigns.” ''It is a way to pass corporate money through the party apparatus and direct it to individual state legislative campaign coffers," explained Galen Nelson, the then-research director at the Massachusetts Money and Politics Project. ''When a donor makes a $500 contribution, you can't allege that there is some access and influence buying. But when a donor makes a $10,000 contribution, their employers can't go unnoticed by the party. It will make the party all the more indebted to the special interest."

The effort, which raised over $3 million, ended up being for naught, as Republicans lost one state Senate seat and two state House seats. But it underscores the fact that Romney’s campaign finance tactics this year, including heavy reliance on a super PAC during the GOP primary to bury his competition in negative ads, and his refusal to reveal bundlers, can trace their roots to earlier efforts to push the envelope of campaign finance laws.

Shares