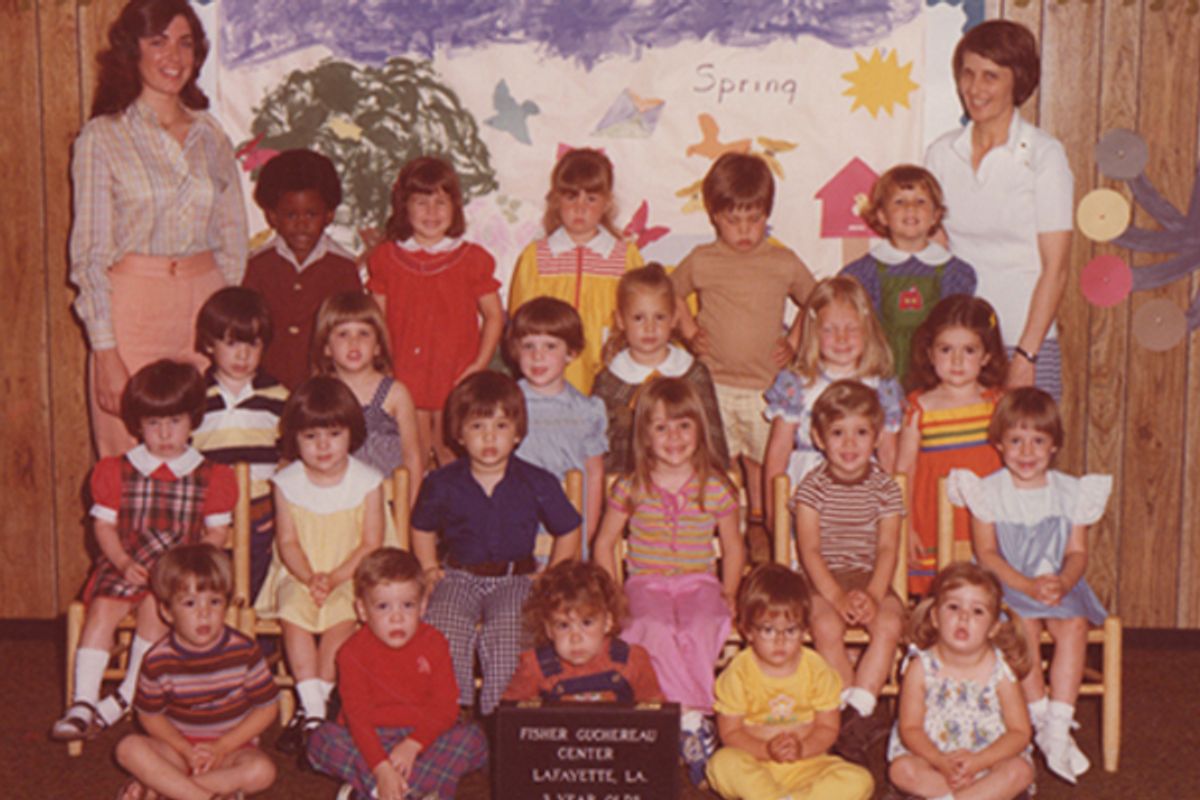

When I say I don’t know any black people, that’s not exactly true. I used to know one. I just haven’t spoken to her in 17 years. Tycely Williams and I met in eighth grade at Vestavia’s Pizitz Middle School in the fall of 1988. I was the skinny new kid with braces, recently arrived after my parents moved my brother and me from Lafayette, La. Freshman year, Tycely and I joined the debate team together. Your typical debate nerd was prone to spend his Friday nights playing Axis and Allies or smoking clove cigarettes while moping around to The Cure. But Tycely was one of the most popular kids in school. Member of the homecoming court, student government chaplain, Class Favorite, Best All Around, Ms. Vestavia finalist — you name it. After we graduated in 1993, we lost track of each other the way people used to do before Facebook. The only thing I’d heard of her since then came from a mutual classmate who’d picked up some random news through the alumni grapevine. “I think she’s friends with Oprah or something,” he said.

Tycely is not friends with Oprah, but she does run her own nonprofit management consulting business in Washington, D.C., which is where I tracked her down in the summer of 2008. If I was going to write a book about why I don’t know any black people, it only made sense that she would be the first person I’d call. I drove down from New York, we had lunch, caught up, and began what has become, for both of us, a very illuminating high school reunion.

During our time, the Vestavia school system as a whole was 4.4 percent black, but the high school itself was closer to 3 percent — only 38 out of 1,238 students. Almost all of them were from Oxmoor, Ala. In our graduating class, Tycely and one other student were admitted because they were teachers’ kids, and only one black student, Chad Jones, actually lived inside the Vestavia city limits. Chad was the superstar athlete, our double state champ in basketball and soccer. His mother, a single parent, had moved to Birmingham from Tupelo, Miss., when he was 12. She worked nights at the local phone utility as they struggled to keep both feet inside the school district, moving from unit to unit in the handful of apartment complexes located on Highway 31. (“I think we lived in all of them,” he says today.) Being the superstar athlete, Chad enjoyed his own set of rules when it came to crossing the color line. Tycely didn’t have that advantage. She had only one chance to fit in, and that was by being the Black Girl with a Really Great Attitude.

“Even on my first day of school,” Tycely says, “I promised myself that I would be nice to everyone, because there was a fear that people would not be nice to me because of my race. But all of my experiences proved otherwise. I never had to be anything other than who I was. I think I was able to make as many friends as I did because I had a level of sensitivity that most teenagers don’t have, and I had that because I was black. There were skaters and jocks, and this group wouldn’t talk to that group — I never fell victim to those classifications, because I was so cognizant of being classified myself. I tried to learn everybody’s names, be friendly to everyone.”

Much like the self-assured girl in Sue Lovoy’s first class, Tycely crossed the color line so fast it never had a chance to hold her back. In a world without black people, it was her advantage to define what black was; we didn’t know. And if black meant Tycely, then black was pretty great. By the time we got to high school, Tycely says, she’d crossed so many lines and had so many friends that she’d neutralized whatever racial animus might have come her way. When pressed to dredge up all the racist things that had happened to her in Vestavia, she didn’t have much to offer. Racking her brain, she could really only come up with one, and then not even something directed specifically at her. “After a football game,” she recalls, “a bunch of Vestavia kids were hanging out, and of course I’m the only black kid. But we were playing Homewood, and Homewood had a lot of black guys on their team. And as they were walking back to their bus, this Vestavia kid said, ‘You know, I hate those niggers.’

“Then one of the cheerleaders was like, ‘Oh my God, how could you say that in front of Tycely?’ Not ‘How could you say that?’ but ‘How could you say it in front of Tycely?’ ”

To which the young man shrugged and offered the standard Southern defense, “What? She’s not like them.”

“I dismissed it,” she says of the incident. “I just felt sorry for people. It wasn’t their fault they were ignorant. I had a lot of kids say to me that I was the only black person they’d ever spoken to besides their maid. I’d invite friends over to visit, and they’d be shocked that I lived in a normal, regular house. They’d say, ‘My parents were really nervous for me to come over here.’ It wasn’t their fault their parents were so fearful and afraid — of what, I don’t know. Going to Vestavia is supposed to be all about getting this great education, but it’s not really about getting an education, because if your parents were concerned about giving you an education, they would educate you about the fact that there are black people who can read and write.”

When Brown v. Board of Education ruled that segregated educational facilities were harmful, the court’s decision focused almost exclusively on the psychological damage segregation caused to black children, the feelings of inferiority they developed by being stigmatized as second-class citizens and lesser human beings. Whites were assumed to be the healthy, well-educated norm. And because we were the norm, rarely did anyone stop to ask, “How is segregation screwing up the white kids?”

The answer, it turns out, is quite a lot.

Vestavia was seriously serious about education. Less than twenty years after bolting from the overcrowded classrooms of the county, our high school had risen to become, arguably, the best public school in the state. In 1991, the U.S. Department of Education officially designated us a Blue Ribbon School; some people came from Washington and gave us a flag.

But Tycely’s right: if education were really the goal, how good could our education have been if we weren’t actually educated about this integration thing in which we were supposedly the key players? Our history textbooks had improved, but barely. The entire civil rights movement had grown to a good three, three and a half pages — now with Martin Luther King and everything. Black History Month might get you a grainy, warbly filmstrip about Jackie Robinson, but then it was back to the three branches of government.

High school curricula suck everywhere, of course, not just in Alabama.

But what was uniquely perverse for us was the community’s collective, blue-ribbon ability to ignore the elephant in the classroom. The Oxmoor busing program was still in full swing. We were a living experiment intended to repair centuries of racial animosity, yet this was never discussed. Ever. I polled dozens of my former classmates, and no one can remember any official acknowledgment of or discussion about the Oxmoor kids’ situation: who they were, why they were being bused in, where they were being bused from, or even what busing was. Vestavia’s botched retreat from U. W. Clemon’s desegregation suit was the only reason our school existed. Yet as far as we were taught, God created Vestavia in six days and went golfing on the seventh.

Between 1970 and 1980, Birmingham tipped from majority white to majority black. So did most every major metropolis across the country; they became donut cities, rings of white suburbs surrounding a black urban core. My classmates and I were born in 1974 or 1975, right at the midpoint, just as that wave was beginning to crest and break on the suburban shore. We were the Children of White Flight, spirited away and raised in captivity. “Y’all were kept in a box,” Jerona Williams says. We were. When the school hosted a foreign exchange program my junior year, it was with a group of kids from Denmark — the only place on earth actually whiter than Vestavia Hills.

As we began to go off to college in the 1990s, Rodney King was viciously beaten and O. J. Simpson did or did not kill a white lady and suddenly race was everywhere. President Clinton was all over TV calling for a National Conversation About It. Words like “multicultural” and “diversity” started creeping into the lexicon. But in the eighties, back when we were growing up, it seemed as if this whole black/white thing was way down on the to-do list, somewhere below “Fix Levees in New Orleans.”

Black America’s only real intrusion into our consciousness came through popular culture: professional sports, bootleg hip-hop cassettes our friends were passing around, and "Cosby." With a five-year run as the No. 1 rated sitcom in the country, "The Cosby Show" normalized blackness for white America. The Huxtables went through the same ups and downs as everybody else. Theo missed curfew! Vanessa’s got boy problems! The message to kids like me couldn’t have been clearer. Black People: They’re Just Like Us.

And in the end, that’s how we related to Tycely. She was the Huxtable kid, our wacky sitcom neighbor, the black girl who’d whirl into class, toss off a few sassy catchphrases, and then exit with the applause sign going. On debate trips, we’d crack jokes about her having to sit at the back of the bus, and she’d snap back some line about Black Power or fighting the man. Then we’d all laugh and go to the food court. It was a game, a way to defuse the tension we all knew was there underneath the surface. And Tycely went right along, quite deliberately. “It was a coping mechanism,”she says, “always making the issue of race something that people could laugh about. It made people comfortable because they knew I would never be confrontational.”

It worked. And in truth, it was her only option.

Reprinted by arrangement with Viking, a member of Penguin Group (USA) Inc., from Some of My Best Friends Are Black: The Strange Story of Integration in America by Tanner Colby. Copyright (c) 2012 by Tanner Colby.

Shares