When one of the world’s richest living artists orders you to stop making art, you do it. Or do you? That is what Chuck Close has done to me. In response, I have developed a 100-year plan that will allow my digital art to outlive any threats of legal action.

I started working on my Chuck Close Filter in September of 2001. The idea came to me the month prior, when I flew to Los Angeles for the Adobe Design Achievement Awards. The creators of Photoshop gave me first place in the Creative Illustration category for my “Barcode Jesus” portrait. I felt that my creative efforts had finally been validated, even though most people still considered computer art to be a lesser medium. One person in particular, an artist whom I really admired, seemed to have a big problem with computers as vehicles for art. He referred to them as “labor-saving devices.” This was Chuck Close.

I started working on my Chuck Close Filter in September of 2001. The idea came to me the month prior, when I flew to Los Angeles for the Adobe Design Achievement Awards. The creators of Photoshop gave me first place in the Creative Illustration category for my “Barcode Jesus” portrait. I felt that my creative efforts had finally been validated, even though most people still considered computer art to be a lesser medium. One person in particular, an artist whom I really admired, seemed to have a big problem with computers as vehicles for art. He referred to them as “labor-saving devices.” This was Chuck Close.

I have been working with computers (both artistically and otherwise) since 1988, when I was 12 years old. At the time, I was living in Tampa, and my uncle gave me a Tandy computer with Print Shop software. I was always driven to tinker, to figure things out, to challenge myself and make work I loved. As I got older, I started to feel an obligation to stand up for this artistic medium that I believed in. I wanted to prove all the naysayers wrong.

Allow me to explain how the Chuck Close Filter works: I start by using Photoshop to dissect Close’s portraits into hundreds of tiles. I find the original images in art books and scan them at a resolution high enough to capture the halftone dots used in the printing of color plates. Due to camera lens distortion, the portraits are never perfectly square. I then search for the faint pencil marks that Close made to define the underlying grid. Finally, I select each tile using the rectangle marquee tool in Photoshop. It takes me approximately eight hours to disassemble each portrait.

From left to right: Chuck Close’s painting of Lucas; Blake dissecting the mosaic in Photoshop; 847 mosaic tiles (click to enlarge)

From left to right: Chuck Close’s painting of Lucas; Blake dissecting the mosaic in Photoshop; 847 mosaic tiles (click to enlarge)Once I have all the tiles separated into individual files, I use an action script that arranges the blocks into any image I want. This automatic process took me six months to figure out. To make the portrait my own, I use the magic wand tool in Photoshop, which allows me to select a single shade of gray and then replace the pixels with my designer tiles.

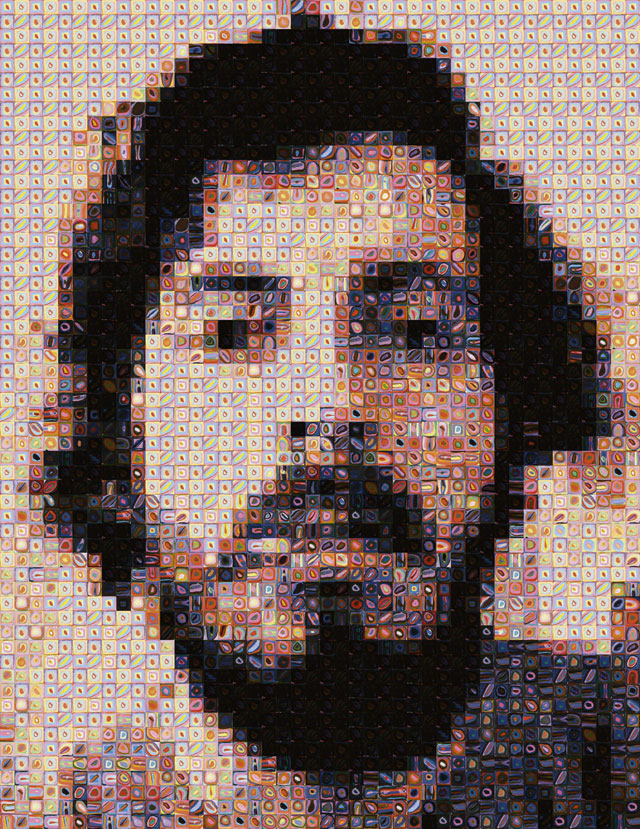

From left to right: Scott Blake’s version of Lucas, version of Phillip made with Lucas tiles, self-portrait with Lucas tiles (click to enlarge)

From left to right: Scott Blake’s version of Lucas, version of Phillip made with Lucas tiles, self-portrait with Lucas tiles (click to enlarge)In 2001, the speed of the internet was still very slow, and I knew I would have to wait a couple of years for the technology to catch up to my imagination. In the meantime, I experimented with creating animations using my Chuck Close Filter.

In the fall of 2002, I had the opportunity to show my work on a giant, 10-foot video wall at the Savannah College of Art and Design. Seeing a Chuck Close painting talking in real time was awesome. I began to wonder how long it would take for Moore’s Law to speed up and make it possible to create a “Chuck Close Mirror” — meaning a mirror that could render you reflecting instantly into the artist’s recognizable style.

Finally, in 2008, the internet became fast enough to accommodate the Chuck Close Filter. I registered freechuckcloseart.com in February 2008, hired a programmer to help me with the interface and made the site available to the public the next month. People could upload their own images, and in 30 seconds, the filter would render a high-resolution digital mosaic. The final images were 8 x 10 inches at 300 dpi, around 2 megabytes per file. The program was stable, but it still crashed some browsers in the beginning. These days, most people eat 2MB files before breakfast.

I have been following Close’s work for over 13 years. In 1998, I drove ten hours to see an exhibit of his at the Seattle Art Museum, and I was completely blown away. I’ve seen videos of him painting and photos of his work in progress, so I understand how he creates his images. I believe my digital mosaics were not copying his art but rather a logical extension of the creative process.

* * *

“Creation requires influence.” —Kirby Ferguson, Everything Is a Remix

Chuck Close Filter animation tests, aka “Chuck Close TV”

Chuck Close Filter animation tests, aka “Chuck Close TV”I take offense when my art is labeled derivative, even if the opinions are well-intentioned. I know it’s just a word, but my art transforms the original into something different, adding new expression over and above the earlier work. I prefer the term “appropriation,” which refers to the use of borrowed elements in the creation of a new piece.

There are other appropriation artists making a living, for instance, Sherrie Levine: she created copies of Walker Evans photographs that were identical to the originals but conceptually very different. Shepard Fairey, on the other hand, has been accused of plagiarism, and not just in regards to the the Obama “Hope” image. My favorite part of this article examining his source materials discusses Roy Lichtenstein and the distinction between appropriation and plagiarism:

When Lichtenstein painted “Look Mickey,” a 1961 oil on canvas portrait of Mickey Mouse and Donald Duck, everyone was cognizant of the artist’s source material — they were in on the joke. By contrast, Fairey simply filches artworks and hopes that no one notices — the joke is on you.

I never intended to rip off Chuck Close, so when he emailed me in November 2010 threatening legal action, I did exactly what he said and took my filter offline immediately. Still, I feel obligated to point out that Close is the 14th richest living artist, worth a staggering $25 million. I really don’t think any work I make is going to “jeopardize” his career or his livelihood.

Here is what he wrote (in all caps):

YOU DO NOT HAVE PERMISSION TO USE MY WORK WHICH IS COPYRIGHTED. NOR DO WISH TO BE ASSOCIATED WITH YOUR PROJECT. YOU MUST SHUT DOWN YOUR WEBSITE IMMEDIATELY OR I WILL BE FORCED TO TAKE LEGAL ACTION.

I replied:

I have attempted to get in touch with you. I think your art is great. I drove 10 hours to see your exhibit at the Seattle Art Museum in 1998 and was blown away. I wish we had met under better circumstances. I understand you do not want me to continue my Free Chuck Close Filter, but I would like the opportunity to talk with you before you take any legal action. I believe my website is not copying your art, but rather is a logical extension of the creative process. Please consider talking with me before you make legal decision, from one artist to another.

Close wrote back:

Even if your motives are not bad, I still do not want my work trivialized. I must fight you because if I know of your project, and do nothing to exercise my legal rights, that will put me in a position where I can’t fight the next, even more egregious usage of my copyrighted image and use of my name. It may be an amusing project and many people might like it, but it is MY art that is trivialized, MY career you are jeopardizing, MY legacy, which I have to think about for my children, and MY livelihood. I must fight to protect it. I hope you will realize the harm you are doing me and my work that you claim you admire and voluntarily shut down the site so as to avoid a law-suit.

I responded:

I respect your decision, and I have shut my free online filter down. I feel obligated to help stop this from happening again. I believe it is better to respond to the situation than delete the project without any explanation. Please review http://www.freechuckcloseart.com.

He wrote:

Thank you so much for your decision. I must say I didn’t expect it. It means a lot to me that you were able to understand my point of view. Thank you. Im in Germany till the end of December, but after I’m back and if you are in New York City, come by and say hello.

The last thing I said to him was:

Thank you for accepting my sincere apology, and especially for inviting me to your New York City studio. I live in Omaha, Nebraska, but I might make a special trip just to see you.

Deep inside, I knew I had a plan; however, I wanted to give Close time to calm down and myself time to figure out a legal strategy. Luckily, I am friends with an intellectual property lawyer here in Omaha. He is very sympathetic to visual artists, and he generously gave me some excellent feedback on my situation.

Right around that time, in October 2010, CBS Sunday Morning aired a segment about Mark Twain’s autobiography. The book was released 100 years after Twain’s death. I asked my lawyer friend if I could release my Chuck Close Filter 100 years after Close dies and his copyright runs out; my lawyer assured me that I could do so without fear of reprisal. I have not made Close aware of my plans, but if he finds out, I would be surprised if he wasn’t insulted. Don’t get me wrong, I know we will both be dead in 100 years, but the point is that our art will live on, and that is what matters to me most. We all have a legacy to think about; Chuck Close isn’t the only one.

Close is known to be very adamant about not accepting portrait commissions, so if you are not lucky enough to be one of his chosen sitters, you will never get to see your face immortalized in his signature style. I simply wanted to make his art accessible to the masses in a new and exciting way. Close is all about “process,” and I feel what I’m doing is the next logical step in that process. He makes work that looks like pixels, so why not make it out of pixels?

Writing all this down makes me feel like a wimp for not standing up to him when he first emailed me, but I took his threats seriously, and I really cannot afford to fight him in court. I respect him as an artist, but this experience has begun to make me lose respect for him as a person. I did a little research into his history and found some interesting quotes.

* * *

“The secret to creativity is knowing how to hide your sources.” —Albert Einstein

Stephen Colbert interviewed Close in August 2010. When Colbert jokingly asked, “Do you ever run out of toner?” in reference to Close’s painting “Mark,” completed in 1979, Close replied, “I was there before computer-generated imagery.” This statement is categorically untrue.

In 1963, three years before Chuck Close started painting from photographs, Ken Knowlton developed the BEFLIX programming language for bitmap computer-produced movies. Each frame of Knowlton’s animations contained eight shades of grey at a resolution of 252 x 184 pixels.

Leon Harmon & Ken Knowlton, “Studies in Perception #1″ (1966), computer-produced mural, as shown in the 1968 MoMA “Machine” show, 5 x 10 feet (© Leon Harmon & Ken Knowlton)

Leon Harmon & Ken Knowlton, “Studies in Perception #1″ (1966), computer-produced mural, as shown in the 1968 MoMA “Machine” show, 5 x 10 feet (© Leon Harmon & Ken Knowlton)In 1966, Leon Harmon and Ken Knowlton began experimenting with computer-generated photomosaics, creating large prints from collections of small symbols. One of their images was printed in the New York Times on October 11, 1967. It was also exhibited at one of the earliest computer art exhibitions, The Machine as Seen at the End of the Mechanical Age, at the Museum of Modern Art in New York City from November 25, 1968 through February 9, 1969.

Chuck Close, “Big Nude” (1967), acrylic on canvas, 9’9” x 21’1” (image via “Chuck Close” book published by Museum of Modern Art, September 2002)

Chuck Close, “Big Nude” (1967), acrylic on canvas, 9’9” x 21’1” (image via “Chuck Close” book published by Museum of Modern Art, September 2002)Amazingly, Close painted a reclining female nude in the fall of 1967, right around the time when Harmon and Knowlton’s nude was published in the Times. Talk about synchronicity! I am shocked no one has ever made this connection before. I’m not trying to say that Close copied Harmon and Knowlton’s work; I’m trying to say that Close was not the first of his kind. The art world is an ever-evolving community. With all the art being made around the world, there are bound to be similarities. I just want to underscore that Close was not “there” before computer-generated imagery.

1973 cover of “Scientific American” on the left and Leon Harmon’s “Abraham Lincoln” (1973) on the right.

1973 cover of “Scientific American” on the left and Leon Harmon’s “Abraham Lincoln” (1973) on the right.Close and the art historians that were paid to write his books like to talk about the 1973 cover of Scientific American as the first appearance of pixelated imagery. I find it hard to believe that Close never saw Harmon and Knowlton’s art or heard about the computer art show at MoMA in 1968. Close moved to New York City in the fall of 1967; his studio on 27 Greene Street was a few miles from the museum.

* * *

“Only those with no memory insist on their originality.” —Coco Chanel

I found another great video clip, from the Sundance Channel series Iconoclast. When Close was asked, “What is an iconoclast?” he replied, “I don’t think about the past, and I don’t think about tomorrow.” His lack of perspective and boasting about ignoring the past disgusts me. He needs a history lesson, starting with the famous quote by George Santayana: “Those who cannot remember the past are condemned to repeat it.” Close needs to stop perpetuating the illusion that his work is totally original.

In the same interview, Close proudly admitted that he didn’t even know what the word “iconoclast” meant. I assume the TV producer gave him the definition, to which he responded, “If it means smash your icons, I think they should be smashed with love and affection.” With my work, I am doing just that: I am smashing my icon with love and affection. Unfortunately, as a result, our work has collided.

I believe my art is fair use, but I don’t have a war chest to back up that assertion in a courtroom, so the wealthy bully wins by default. My only recourse is to publicize my defeat in order to shine a light on these types of situations. My hope is that Chuck Close develops a sense of shame and regret, realizes his mistake and offers up an apology. I want this article to serve as a point of reference for current and future artists. The worst part about this whole mess is that it makes established visual artists like Close seem petty. By not embracing new and interesting ways of making art, he is contributing to the widening of the generation gap. His irrational fear of computers has made him wildly out of touch with my generation and generations to come. I feel he singled me out because I choose to work in a medium that he finds inferior.

I think Close is confusing enterprise with creativity; they are not the same and in some cases can work against one another. In the end, I believe Close’s misguided and hypocritical actions will do more harm to his legacy than any so-called “derivative art” could ever do. His behavior has left me no choice but to carry out my 100-year plan.

This project started off as a simple college assignment and has quickly turned into a battle for visual artists’ rights. I’m fighting for creative freedom and battling against an antiquated way of thinking that is stifling a new form of artistic expression. It is inevitable, and artists like Chuck Close need to be willing to pass the torch to the next generation.