It’s 1776 in Philadelphia. Congressional delegates “sweat, swat flies, and argue independence.” They retreat to a tavern and casually dump Jefferson with the job of composing a declaration: “Tom, write us something dignified, yet magical.” Once he’s finished, all the congressmen shout out changes at him: “Drop 'independent’;” “Why ‘happiness’ instead of ‘property’? What’s ‘happiness’?”

It’s 1776 in Philadelphia. Congressional delegates “sweat, swat flies, and argue independence.” They retreat to a tavern and casually dump Jefferson with the job of composing a declaration: “Tom, write us something dignified, yet magical.” Once he’s finished, all the congressmen shout out changes at him: “Drop 'independent’;” “Why ‘happiness’ instead of ‘property’? What’s ‘happiness’?”

The process is loud, sloppy, and often chaotic. It also feels like real life.

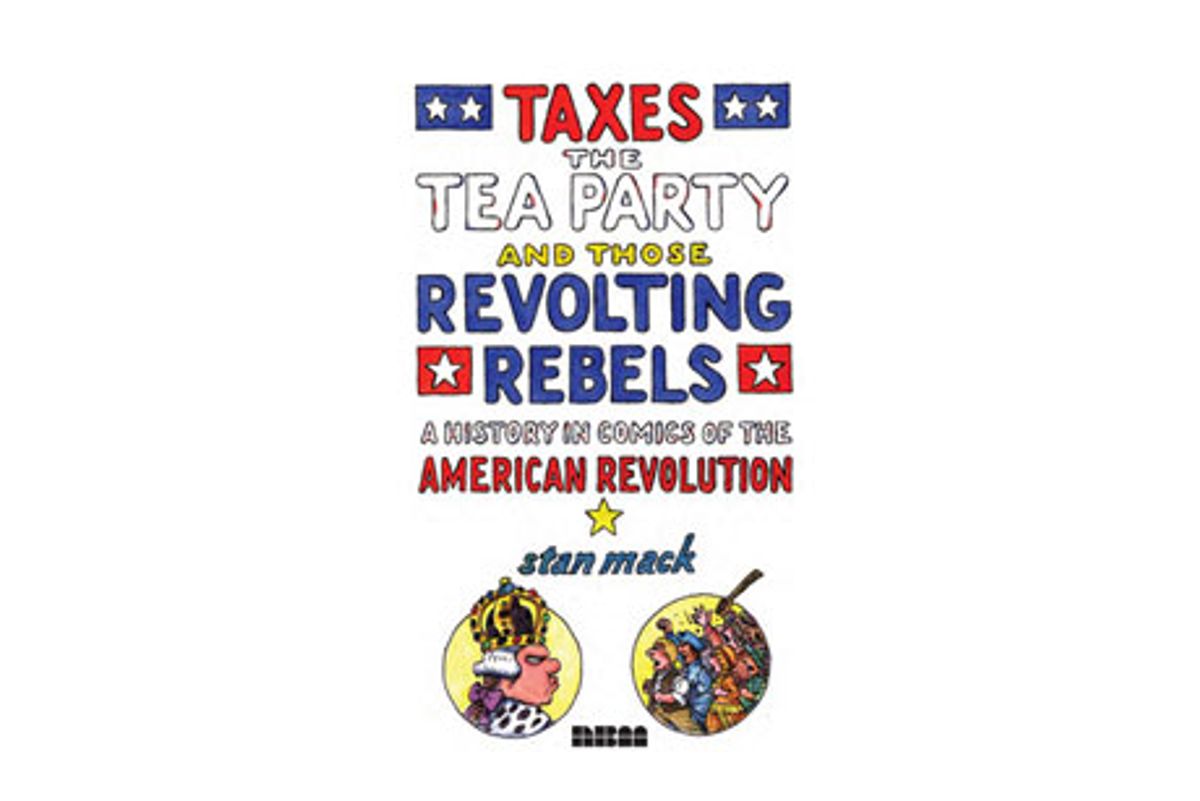

That’s because this graphic narrative of our country’s birth, titled "Taxes, the Tea Party, and Those Revolting Rebels: A History in Comics of the American Revolution", is illustrated by Stan Mack. And Stan is one of the founding fathers of contemporary cartoon reportage, having created Stan Mack's Real Life Funnies for the Village Voice back in the mid-1970s.

"Taxes, the Tea Party, and Those Revolting Rebels," a revision of 1994’s "Stan Mack’s Real Life American Revolution," will arrive in comics stores this month. And he’ll be on two panels at next week's San Diego Comic-Con: “Progressive Politics and Comics” on Thursday, July 12, and “Serious Pictures: Comics and Journalism in a New Era” on Sunday the 15th.

Here’s my conversation with Stan about his book and how it might be relevant to our country today.

This is the second in a series of interviews with Comic-Con speakers. The first, my talk with JT Waldman about his new book with Harvey Pekar, ran last week. Next up: my conversation with Arlen Schumer about his auteur theory of comics, with a spotlight on Jack Kirby.

How would you describe your journey from graphic documentarian to graphic historian?

For my "Real Life Funnies" comic strips, I wandered the streets of New York City in search of life on the wing — telling people’s stories in their own words, sketching them in their natural habitats.

The earliest strips were comic snapshots full of irony and even satire. Over the years, I took on tougher topics and the strips lengthened into short stories, though much of the irony would always be there. Eventually, they threatened to become book-length, and I had to admire the readers who hung in as I crammed more and more words into the same small space. I looked for a bigger apartment to house bigger stories.

I found the apartment: It was a book. The story idea grew out of strips I was doing covering clashes between squatters and the homeless on one side, and the city and real estate interests on the other. I decided to chronicle the American Revolution as a way of sorting out the rights and obligations of citizens and their leaders.

Still, history isn’t the same as real life on the streets of New York, which gets up in your face and hassles you. It sits in 2-D on the page. But it was once real life, as raw, gutsy, and goofy as any of my "Real Life Funnies." It’s just been freeze-dried. I found I could add water and stir vigorously and it came to life.

What inspired you to update your "American Revolution" book?

My book didn’t really need updating, just some fine-tuning and an appropriate title. Looking back, I think my book was ahead of its time. The graphic novel category for writer/cartoonists who wanted to do serious non-fiction didn’t exist when it first came out. "Maus" was pretty much the whole ballgame. I remember watching a clerk in a bookstore in Georgetown take my book out of a box, stare in puzzlement at the cover, and stick it in "Humor."

Later, after the graphic novel genre was established, I did a book on the history of the Jewish people and another on being the caregiver for my partner, Janet Bode, who eventually lost her battle with breast cancer.

Of course I was proud of my Revolution book and wanted to give it a new life. I also could see that the book was very much in tune with today’s politics. Think about it. What’s this election year about? Ideology, individual freedom, taxes, jobs, and the economy! That’s the exact stuff that propelled the colonists to break from England.

How would you compare your approach to "Taxes" with your history of the Jews?

I’d compare the two books two ways. Visually, I wanted to get away from the formal page grid common to literary graphic novels. I think fiction needs a grid, so the writer can better focus on his story. For example, this is what Susan [Champlin] and I did with "Fight for Freedom," our new graphic novel for young people.

But history isn’t art — it’s random, chaotic. Each of my pages looks different, giving, I hope, a sense of the unexpected. There is a grid, but it’s less visible. "The Story of the Jews," done a few years later, carries further the idea of variety in page layout.

Editorially, they are a lot alike. I am very careful to triple-check my historical facts and motivations — not that original documents necessarily agree with each other in the first place. In both books, the fun came when I was able to put words into the mouths of some of the greatest names in history: George Washington, Alexander Hamilton, and John Adams, not to mention Moses and the God of the Jews. The books being the work of a cartoonist, they do all kinda speak out of the side of their mouth, wiseguy-style. Waddaya expect?

And how is "Taxes" … different from other graphic novels about American history?

I was told recently by a college professor that there’s a glut of new graphic books aimed at the education market. Teachers are buying them because they think the students like them. But, he said, most are wordy and boring! I’m sure there are excellent graphic histories out there, too. I’d describe mine as good history with a “street” attitude. And it goes down real easy.

[caption id="attachment_366061" align="aligncenter" width="600" caption="A sample of early draft notes, as Stan was working out the words"] [/caption]

[/caption]

Nice. Okay, how does your book relate to today's Tea Party and Occupy movements?

My book tells the story of the original Occupy movement: the revolting rebels. They didn’t call the movement “Occupy,” they called themselves the “Sons of Liberty.” The Sons conducted the same protests and actions as Occupy, though they also hung enemies in effigy from liberty trees and tarred and feathered Tories when practical. And we learn who threw the first Tea Party — it was the Sons of Liberty themselves. So maybe today’s Tea Party and Occupiers should get together and form a book club ... starting with my book.

If you read my book, you will no longer have to swallow what the right or the left tells you about the Constitution, the Founding Fathers, and the Bill of Rights. You can swallow your own conclusions.

How else does your book address life in America today?

Whether it's health care, immigration, the tentacles of big government, foreign relationships, the environment — all of this year’s political issues seem to come down to a battle between, as I say in my book, Aristocraticks versus Democraticks, profit versus virtue, and individual liberty versus the public good.

Unlike the dangers that people in other countries face if they criticize their governments, about the biggest risk the Tea Party faithful and Occupiers face is having a Fox broadcasting crew chase them down the street waving microphones and cameras. And that’s because our Bill of Rights — which, by the way, was opposed by former revolutionaries John Adams, Hamilton, and Washington, and was pushed for by ordinary citizens until it was included — protects them.

.

You might also enjoy The Insider's Guide to Creating Comics and Graphic Novels, available at MyDesignShop.com.

Shares