David Koch's Hamptons fundraiser for Mitt Romney last weekend drew protests and lots of press, and and it's no wonder why. By now, the story of the Koch brothers is well known. Charles and David, together (and they seem to do everything together), own the world's second largest privately held company, are worth tens of billions of dollars and operate a vast and powerful network of right-wing political organizations trying to take down President Obama. For their political wet work, the Koch brothers have become boogeymen of the left and heroes of the libertarian-leaning right. For critics, the fundraiser was a manifestation of everything wrong with the country's current campaign finance regime.

But there’s another Koch story that’s far less well known: The tortured story of the Koch twins and one of the few things they have in common -- Mitt Romney. While Charles and David get all the attention, there are actually four Koch brothers. Split into two warring pairs, the brothers have fought a decades-long battle of biblical proportions over billions of dollars and control of Koch Industries, the petrochemical giant founded by their father, Fred. On one side were Charles and David, who have controlled the company since 1983 when they bought out William (David's fraternal twin) and Fred Jr., who later alleged that Charles and David cheated them out of $2.3 billion in the sale. (The brothers settled in 2001.) There has been decades of bitter litigation, acerbic personal insults, high-stakes corporate mutinies and palace intrigue befitting a Greek tragedy. In 2009, Bill, as David’s insurgent twin is known, told "60 Minutes" of his brothers’ running of the family business: “It was obvious to me that this was organized crime and management driven from the top down.” Yet David and Bill have found common ground in becoming two of Romney’s most valuable supporters.

The twins’ trouble began nearly a half-century ago, when Fred C. Koch, the Communist-hating patriarch who built an oil and gas empire from scratch and helped found the John Birch Society, died in 1967. When his will was read, it turned out he had disinherited his oldest son and namesake, Fred. Charles, who began working for his father at age 9, took the helm of the family’s multibillion-dollar company, and Fred went off to New York’s art world. Charles, David and Bill had all attended MIT and worked for the company together, but tensions built. In a 1986 New York Times Magazine piece, Mary Koch, the family's elegant matriarch, described Christmas dinner in 1979: ''Bill sat opposite from me at the table. And all he did was make unkind remarks about Charles. I got up and left the table crying.” Bill was always envious of Charles, who was sent away to boarding school so the two could be separated. "We had to get Charles away because of the terrible jealousy that was consuming Billy," Mary told the Times.

Just before Thanksgiving the next year, Bill made a move. He called for expanding the board by two seats, and convinced the son of Koch Industries board member J. Howard Marshall II (best known for marrying a 26-year-old Anna Nicole Smith when he was 89) to use his shares to replace his own father with an ally of Bill. This would have given Bill control of the board and the company. Charles and David counterattacked, preventing the addition of the two seats and winning back the board member’s son, thwarting Bill’s scheme. Bill was dismissed, and he and Fred. Jr. began negotiations to sell their shares to their dominant brothers. They haggled over the price for over a year and eventually talks fell apart. Bill sued, then Charles and David countersued, accusing their estranged brother of libel and demanding $167 million. In court in 1982, Charles said that Bill was ''afflicted with various psychiatric ailments which cause him to be unstable.” (Charles repeated the charge over a decade later, leading Bill to say the accusation of mental illness is “getting stale.”) The parties settled in 1983 for an undisclosed sum, but two years later Bill and Fred sued again, claiming Charles and David had bilked them. The case, and various related litigation, dragged on for years, making it all the way to the U.S. Court of Appeals for the 10th Circuit in 2000. "I don't want to see my brothers in jail," Bill told Fortune in 1997. "But I'm at war."

As the Times reported in 1998, when the case was before a federal jury, "The two sets of brothers now pass silently in the narrow hallways, avoiding eye contact. They have not spoken to one another for nearly a decade, even at their mother's funeral in 1991. ... Today, they talk only through lawyers. Their wives, too, glide silently by one another.” Bill and David own mansions just a few miles apart from each other in Palm Beach and while relations apparently remained strained into the 21st century, the twins seem to have reconciled. Bill told New York magazine in 2010 that David is now “one of my best friends.” Still, just three years ago, Bill accused his brothers’ company of systematically defrauding its subcontractors by taking more oil out of wells than it reports to supplies, thus underpaying them.

But there’s one thing that the twin brothers can agree on, despite their Romulus and Remus-like quarreling: Mitt Romney. Both have held numerous fundraisers for the presumed GOP nominee, and both have apparent personal relationships with the candidate.

Bill and Romney go way back: "He has a personal relationship with Mitt, that goes back to when Bill Koch was in Massachusetts, and that was back in the '80s,” Bill’s spokesperson Brad Goldstein told a Florida radio station in May. Indeed, in one connection between the Koch family and Romney’s world that has apparently gone unnoticed until now, Bill and Fred hired Romney’s then-employer Bain & Co. to do consulting work for their suit against their brothers. One court document from 1997 mentions Bain 35 times.

“William did in fact employ Bain & Co. at his first meeting with that firm on July 19, 1982,” the document states, detailing numerous meetings between Bill and Bain employees. Bill hired the company to help value Koch Industries, along with Goldman Sachs and other Wall Street firms. But Bain clearly played a leading role. As Bill testified of the company’s official valuation, which he doubted: “I thought their values were low and I thought there was a good rationale for a higher value, a higher objective value based upon all the work that Bain had done as well as all the work that other investment bankers had done and based upon the information that we knew at that time.”

There’s no evidence that Romney personally had anything to do with the Koch affair (the court records only mention two Bain employees by name, William Bennett and Fred Coles), but Romney was with Bain & Co. at the time. He left to start Bain Capital in 1984.

More recently, Bill, through his company, the oil and gas distributor Oxbow Carbon, gave at least $2 million to Restore Our Future, the super PAC backing Mitt Romney, making him the third-largest corporate contributor as of late May to the organization that was critical to Romney’s primary success. Last year, Bill also hosted a fundraiser for Romney at his Cape Cod, Mass., mansion, and another one at the Palm Beach, Fla., house. This year, he co-hosted a third fundraiser at a friend’s house in Florida.

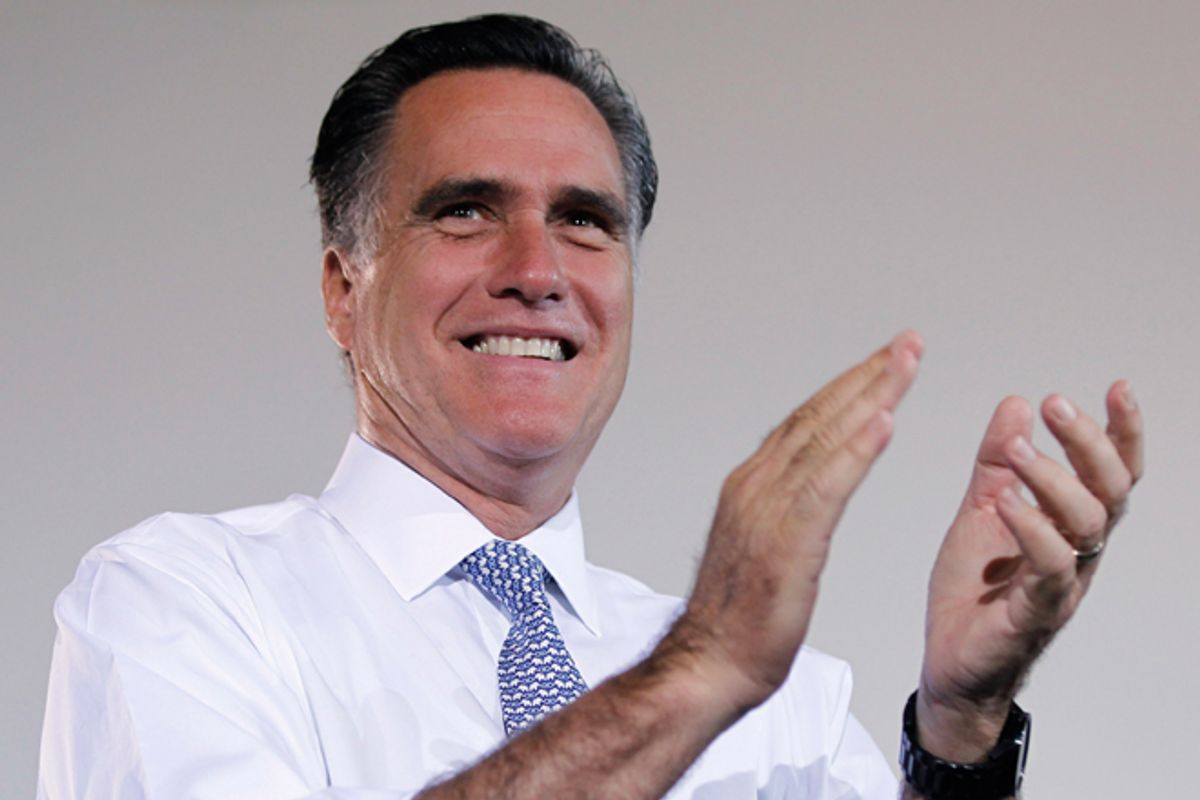

Meanwhile, David Koch held his fundraiser for the presumed GOP nominee at his mansion in the Hamptons last weekend. The event cost $50,000 a plate and was expected to bring in at least $1 million. But it was not the first. David has held a number of other events for Romney, including one of the candidate’s first fundraising events at the critical early stages of the campaign way back in August 2010.

Asked in May by the Boston Globe if Bill had coordinated his Romney giving with David or Charles, spokesman Goldstein replied, “They’re a separate house. They’re a separate deal.”

Shares