On Monday, the Wall Street Journal reignited a battle over money in politics when it reported that labor unions have been spending about four times more on political activity than was previously understood. Using public disclosure forms unions filed with the Labor Department, the Journal concluded that unions have spent over $4 billion on political advocacy at all levels of government since 2005.

“The result,” the Journal explains, “is that labor could be a stronger counterweight than commonly realized to ‘super PACs’ that today raise millions from wealthy donors, in many cases to support Republican candidates and causes.”

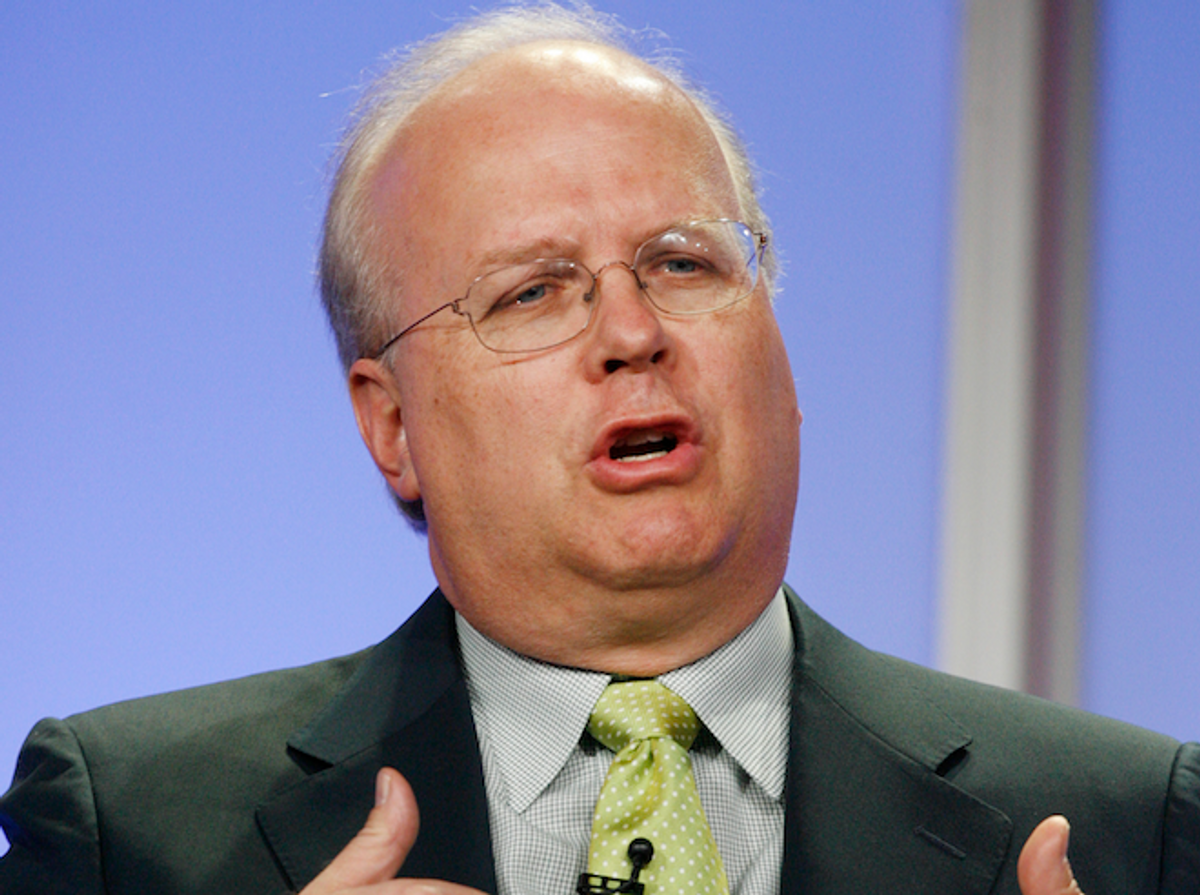

Republicans and proponents of secret money groups saw the report as vindication. Jonathan Collegio, the spokesperson for the Karl Rove-backed American Crossroads and Crossroads GPS, two of the largest outside groups backing conservatives, sent the article to reporters with the subject line “MUST READ.” “Labor unions have traditionally spent far more on political activity than any other sector, and Super PACs like American Crossroads will at best balance them out,” Collegio said.

Indeed, this argument -- that conservative outside spending groups are merely doing what labor unions have done all along, and are thus justified in their activities -- has been a common conservative refrain since the Supreme Court handed down its Citizens United decision in 2010. But is it true?

In terms of sheer money, while it’s difficult to measure accurately or comprehensively, it's probably not even close. In terms of direct contributions to candidates, business groups have given about $618 million to Republican candidates since 2000, on top of another $31 million to GOPers from ideological groups, according to the nonpartisan Center for Responsive Politics. Labor groups, meanwhile, have given under $35 million to Democrats over that same time period. “Whatever slice you look at, business interests dominate, with an overall advantage over organized labor of about 15-to-1,” the Center notes, though business groups divide their giving between Republicans and Democrats, while labor focuses almost entirely on Democrats. In terms of lobbying, labor groups are again hopelessly outspent. Together, they have collectively spent about $502 million on lobbying since 1998 -- less than 11 separate business sectors spent individually. Each of those sectors, including defense and healthcare, have each spent between $1 and 5 billion.

“This parity that supposedly exists,” Sen. Al Franken, a Democrat from Minnesota, said at a press conference this morning in response to a question from Salon, “it’s just not true. ... These Republicans that say that, they’re wrong.” (The event marked the rollout of a new version of the DISCLOSE Act, a bill to make all contributions over $10,000 transparent.)

When it comes to outside spending on ads, of the top five groups so far this year, four are conservative, one is liberal (Priorities USA), and none are labor unions. The first union on the list, the SEIU, comes in at 13th place. The AFL-CIO, the country’s biggest union, is even further down the list, just under Americans for Rick Perry, a super PAC that supported the Texas governor’s ill-fated presidential bid.

But beyond spending, unions operate under a completely different paradigm from the conservative independent expenditure groups in a number of meaningful ways.

First, unions are subject to very strict annual disclosure rules that require them to detail all “political activities and lobbying,” both “direct and indirect.” It’s far more comprehensive than what corporations and super PACs are required to disclose. As the Journal itself even noted, “Comparisons with corporate political spending aren't easy to make. Some corporate political spending, such as donations to the U.S. Chamber of Commerce's political wing, doesn't need to be disclosed. What does have to be disclosed can't be found in a single database or two, as is the case with unions.”

“The fact [is] that the disclosure required for unions is greater than for other kinds of organizations,” Bob Biersack of the Center for Responsive Politics told Salon.

Second, donors to secret money groups and super PACS can have far greater influence than donors to unions’ political activity because union donations are, by nature, far more dispersed. “Our concern is not so much with the total dollars being spent in politics, as the ability of a very small number of donors to exert huge influence on the electoral process through their willingness and ability to contribute huge amounts,” Paul S. Ryan, the senior counsel at the Campaign Legal Center, told Salon. “And that’s where you really see a difference between the c(4)s and c(6)s, like the Chamber [of Commerce], and labor unions.”

“Labor unions are made up of, typically, large numbers of modest-income individuals who, even in the aggregate, give a pretty modest amount of money or resources to their union for political and every other purpose,” Ryan continued. “By contrast, some of the newer c(4)s have been created precisely to avoid limits on contributions and to facilitate the ability of really wealthy people to give big checks.” This is the type of activity that breeds corruption.

Third, union members can opt out of contributing to political activity, while shareholders of corporations cannot, Jeff Hauser of the AFL-CIO pointed out to Salon. “Union political committees are created by an internally democratic proceeding and make endorsements in line with union membership’s preferences,” the AFL-CIO said in a statement responding to the Journal article. And under federal law, union members can fill out a form to opt out of having a portion of their dues go to political activity if they disagree with the organization's politics. Corporations, on the other hand, do not have to disclose to their investors how they spend money for political advocacy and lobbying, let alone let investors have a say in which candidates or causes the corporation should support. So investors cannot opt out because they don’t even know. “If we give union members the right to opt out of, to refuse to fund union political speech, we ought to give shareholders the right to opt out of funding corporate political speech,” said Benjamin Sachs, a labor-law expert at Harvard, told NPR last month.

Shares