While conservative politicians and pundits have been denouncing the welfare state for three-quarters of a century, conservative theorists have spent much of that time trying to devise a conservative version of the welfare state. All of the proposed models of a conservative welfare state are less efficient and less fair than the progressive alternatives. All, to date, have failed to win widespread popular support. But the fight is far from over.

In the words of the late Irving Kristol, “The idea of a welfare state is perfectly consistent with a conservative political philosophy – as Bismarck knew, a hundred years ago. In our urbanized, industrialized, highly mobile society, people need governmental action of some kind … they need such assistance; they demand it; they will get it.” Intelligent conservatives have always understood that parties and movements of the right cannot simply abolish the economic safety net for the elderly, the unemployed and the sick, and replace it with nothing at all.

But the American right has been unable to settle on a single alternative to the institutions like Social Security, Medicare and Medicaid, unemployment insurance, and means-tested public assistance bequeathed by the liberals of the New Deal era between Franklin Roosevelt and Lyndon Johnson. Each of the factions of the right — the corporate right, the social conservative right and the libertarian right — has proposed its own version of the conservative welfare state.

The oldest attempt to create a conservative welfare state was sponsored by elements of the business community in the early 20th century. This is sometimes known as “welfare capitalism.” As an alternative to government benefits and minimum wages, American business leaders as different as the reactionary Henry Ford and the progressive Gerard Swope of GE favored paternalistic companies that would not only pay decent wages but also provide health insurance, pensions and in some cases child care.

Franklin Roosevelt’s National Recovery Administration (NRA), ruled unconstitutional by the Supreme Court in 1935, is denounced today by ignorant conservatives and libertarians as an example of collectivist radicalism. In fact it represented a pro-business spirit of corporate welfare capitalism, not statism. Instead of a single public package of minimum wages and benefits, the NRA sought to encourage each industry, on the basis of employer-labor collaboration, to create its own industry-wide minimum benefits, so that generous, paternalistic companies would not be undercut by rivals that paid low wages and provided no benefits.

Although the NRA did not survive, welfare capitalism with its employer-based benefits flourished and remains important to this day. In the 1950s Eisenhower encouraged using the tax code to subsidize employer-provided health insurance, and in the 1970s Nixon proposed making employer-based health insurance mandatory.

But conservative welfare capitalism assumed an economy dominated by large corporations with lifelong employment. Although most Americans still receive their health insurance through their employers, in the last quarter century a growing number of workers have become part-time employees, and many companies have replaced defined benefit pensions with unstable and inadequate 401Ks for their full-time employees. No conservatives today would call for mandatory employer benefits, as Nixon did. The tradition of paternalistic welfare capitalism is extinct on the right.

From the 1970s to the 1990s, social conservatives and some neoconservatives boosted “intermediate institutions” as the answer to the liberal welfare state. Drawing on the British politician and philosopher Edmund Burke’s defense of “little platoons” and conservative sociology that stresses the dehumanizing, alienating effects of modern bureaucracy, these conservatives hoped that many of the welfare functions of modern federal, state and local governments could be performed through more intimate communities like charities and churches. Marvin Olasky, a professor at the University of Texas, led the campaign for creating a “faith-based” economic safety net.

At the same time, influential libertarians on the right had a radically different approach, inspired by Milton Friedman, leader of the Chicago School of free-market economists. The idea of a quasi-feudal alliance between church and state did not appeal to free-market radicals. Like the neoconservative Irving Kristol, Milton Friedman, who called himself a “classical liberal” rather than a conservative, and his followers, realized that the right could not abolish social insurance and aid to the poor without providing some alternative.

Their alternative has been a voucherized welfare state, in which the federal government provides citizens with vouchers in the form of tax credits, which can be used to purchase financial assets for retirement and private health insurance. The premise is that competition among providers for voucher money will drive down costs, reducing federal spending on the economic safety net without increasing individual insecurity. (The premise is dubious, because in imperfect markets characterized by monopoly or oligopoly, like nearby hospitals and prestigious universities, competition does not work to lower prices, while subsidies allow producers to hike prices.)

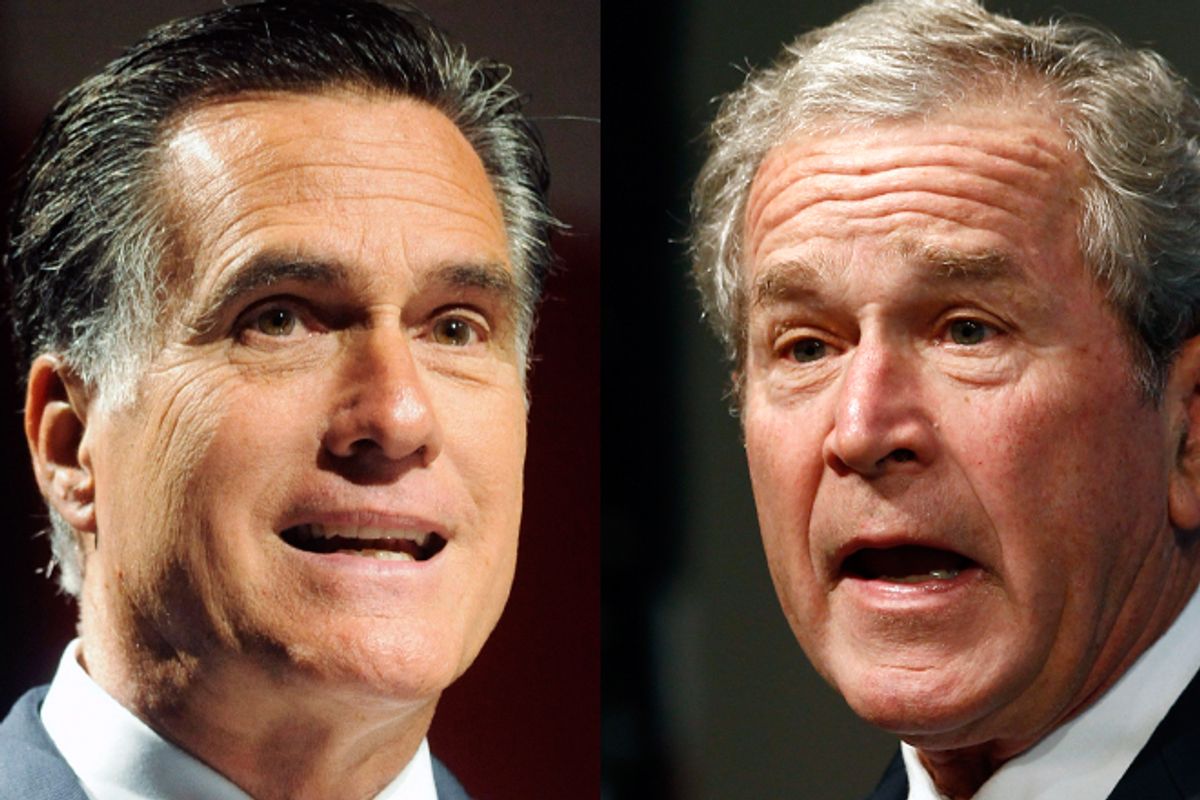

These two alternative versions of the conservative welfare state were both endorsed by George W. Bush, who backed “faith-based initiatives” as well as a tax-credit-based “ownership society.” John J. Dilulio Jr., one of the thoughtful champions of intermediate institutions, blamed the failure of the faith-based approach on what he derisively called “Mayberry Machiavellis “ in the Bush administration — “staff, senior and junior, who consistently talked and acted as if the height of political sophistication consisted in reducing every issue to its simplest, black-and-white terms for public consumption, then steering legislative initiatives or policy proposals as far right as possible … But, overgeneralizing the lesson from the politics of the tax cut bill, they winked at the most far-right House Republicans who, in turn, drafted a so-called faith bill (H.R. 7, the Community Solutions Act) that (or so they thought) satisfied certain fundamentalist leaders and Beltway libertarians but bore few marks of ‘compassionate conservatism’ and was, as anybody could tell, an absolute political nonstarter.”

Bush’s “ownership society” was as much a political failure as his faith-based initiative. His second-term push for the partial privatization of Social Security, a longtime goal of libertarians and Wall Street interests salivating at the prospect of the diversion of Social Security payroll taxes into the stock market casino, was so unpopular with Republican as well as Democratic voters that a Republican-controlled Congress never even brought the proposal to the floor of the House or Senate for a vote.

Ironically, the one great victory of the libertarian attempt to voucherize the welfare state is the Affordable Care Act — Obamacare. Its models were the conservative Heritage Foundation plan of the 1990s and Mitt Romney’s “Romneycare” in Massachusetts. Combining a mandate to buy private health insurance with means-tested subsidies, Obamacare, in effect, rejects the progressive alternative of universal public social insurance and replaces one conservative welfare state approach (employer-based benefits) with another conservative approach (Friedmanite welfare vouchers). Just as only the arch-anticommunist Nixon could open diplomatic relations with communist China, so only a Democratic president could enact the right’s healthcare plan.

This brings us to the present. Today’s inherited economic security system is an incoherent mixture of programs reflecting different conceptions of the welfare state: a public welfare state (both universal social insurance and means-tested public assistance); employer-based welfare capitalism (employer-provided health insurance and pensions); intermediate institutions (tax-favored private charity) and welfare-market vouchers (the Affordable Care Act).

Employer-based benefits are in a long-term decline, and the dwindling influence of the religious right is reducing the constituency for faith-based welfare. In practice, therefore, the debate is over only two ways to fill the gap left by the decline of employer-based welfare capitalism: an expanded public welfare state -- either in the form of an expansion of universal programs like Social Security and Medicare or an expansion of means-tested programs like Medicaid and food stamps -- or a voucherization of the entire economic security system, along the lines of Obamacare.

In the coming battle, the right, having abandoned welfare capitalism and faith-based institutions, is likely to unite behind the libertarian voucher policy, while the Democrats will be split three ways among neoliberals, who are inclined to unite with the right in favor of vouchers; social democrats, who favor an expansion of universal middle-class programs; and what Mike Konczal calls “pity-charity” liberals who want to cut spending on the middle class to fund bigger means-tested programs for the poor. Far from being a victory for progressives, the Supreme Court’s decision in the Affordable Care Act opens the door to the voucherization of Social Security and Medicare, by means of individual mandates to purchase private retirement and healthcare goods and services.

To make matters worse, voucherization promises an endless stream of guaranteed profits to the CEOs and shareholders of private for-profit companies that would replace the public Social Security and Medicare administrations and extract income from Americans forced by “individual mandates” to purchase private health insurance, invest in private stock market accounts, and buy private annuities. The need to pay middlemen with high salaries would drive up the costs of retirement and healthcare, while the recycling of monopoly profits into campaign contributions would deter Congress from regulating prices in the new, voucherized welfare state.

With the right united and the left divided, and big money favoring the privatization of America’s welfare state, the prospects for an expansion of universal tax-based middle-class social insurance in the U.S. are not good. Which is a tragedy for America, because universal public social insurance is by far the most efficient and least corrupt way to design a modern economic safety net.

Shares