BUENOS AIRES, Argentina — Guillermo Perez Roisinblit leads an ordinary middle-class life. He lives in a quiet hamlet outside Buenos Aires with his wife and two young children, making the 40-minute commute by train to Argentina’s capital during weekdays.

But Perez Roisinblit’s story is far from normal. Indeed, only his family and an unwavering need for justice have kept him going through the turbulent and deeply confusing last decade.

“I know the truth now. I now know what my real origins are, who my real family are, what happened to me and where I was really born,” says the 33-year-old. “But more than this, I need justice, because someone is responsible for all of this. Someone played God and decided who lived, who died and who brought up the children of the victims.”

Perez Roisinblit is one of Argentina’s stolen babies. He was born to left-wing activist parents who were arrested during the last military dictatorship (1976-1983) and taken to a clandestine detention center because of their beliefs.

Then they were “disappeared” by the armed forces – possibly drugged and thrown from planes into the murky waters of the River Plate, one of the regime’s favorite methods to ensuring bodies never showed up.

But even by the standards of mass murderers, the junta’s logic was warped. They would wait for pregnant mothers to give birth before killing them. The regime abducted the babies and brought them up in military families to ensure they grew up with the “correct” ideological outlook.

Earlier this month, two former regime presidents, among others, were convicted for overseeing the abduction of some 500 babies.

The case was historic because it was the first time Argentina’s justice system recognized that this was a systematic, state-sponsored plan. Previous trials had convicted individuals for what were, at the time, seen as isolated cases.

Perez Roisinblit remembers a day back in 2000, when a girl named Mariana came to his workplace, asking lots of questions about him. Suspicious, he refused to talk to her, but accepted her letter. It said she thought they were brother and sister — and the children of disappeared parents.

That’s when his world began to fall apart. “You have to realize, when you’re not looking for your real origin — because I wasn’t searching for my origins — it’s very difficult to accept,” he explains.

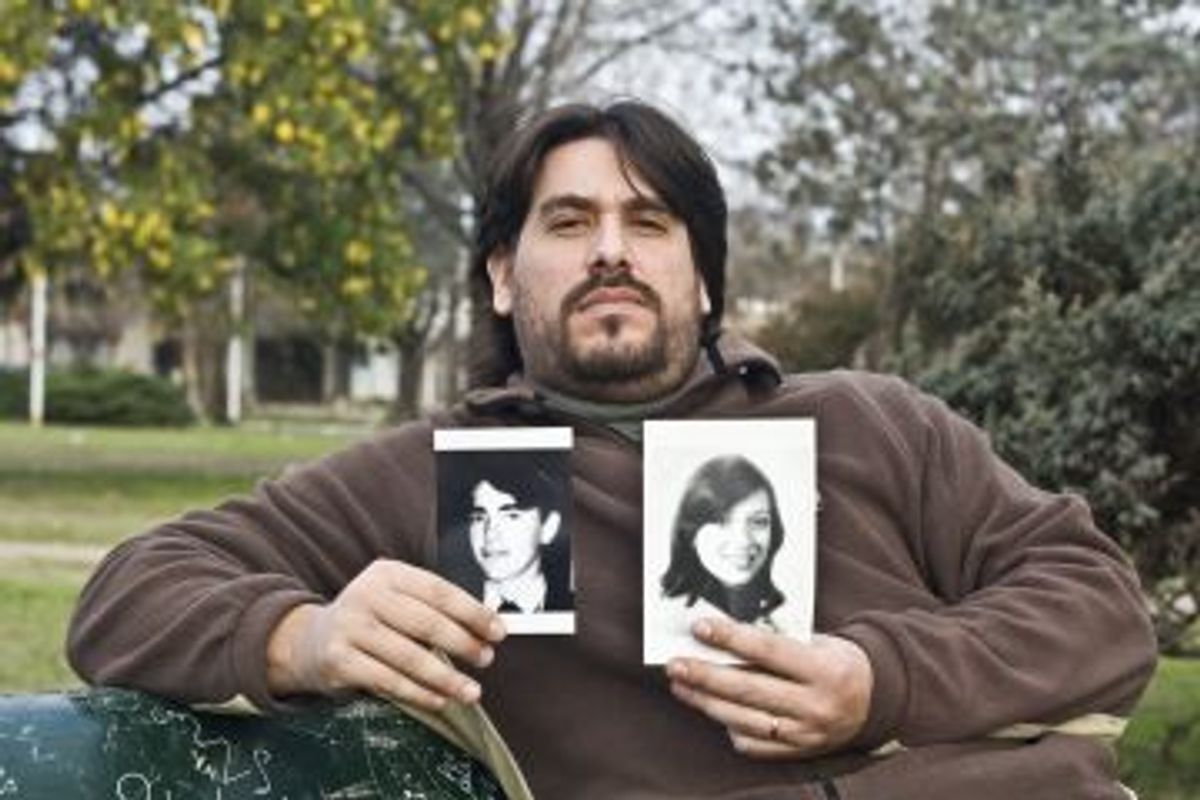

Mariana’s letter was tucked inside a book. When he opened the pages to read the letter, he was suddenly confronted with two black-and-white pictures. He had no idea at the time that these people were actually his real parents but he found his resemblance to the man in the photo “frightening.”

The letter created enough doubt for him to agree to talk with the Abuelas de Plaza de Mayo, a group of grandmothers that have spent the last 30-plus years searching for the children of their disappeared sons and daughters.

He agreed to give a DNA sample to be compared with a national database. A month later he was coming to terms with the daunting reality that he wasn’t the son of Air Force intelligence officer Francisco Gomez and his wife. They were, in fact, his abductors. His real parents were dead, and he had been born in the notorious ESMA detention center.

Perez Roisinblit is one of 105 stolen babies who have managed to learn of their true background since the return to democracy. He compares the confusion it created to “someone pulling the ground from under your feet and you’re starting to fall.” Suddenly everything he thought he knew about himself and everything he’d been brought up to believe was called into question.

The hardest part was the trial of his abductors, which finally reached a verdict in 2004 after dragging on for several years. Gomez was sentenced to seven years in prison and his wife three and a half for abduction.

Having to deal with a highly politicized court case that frequently made the news headlines, Perez Roisinblit felt like he had to decide between his new family and the one he’d known all his life. “I didn’t want my blood [or DNA] to become the key evidence in the trial of the people who had brought me up,” he adds.

Perez Roisinblit admits to mixed feelings for the people who deceived him on such an epic scale. He has dropped his Gomez surname in favor of the two last names of his parents (Patricia Roisinblit and Jose Perez). Yet he continues to be known as Guillermo, even though he now knows his real parents wanted to call him Rodolfo.

He also admits to maintaining links with Gomez’s wife and pleads that her name not be included in this article. His relationship with Gomez, absent when he grew up after an acrimonious divorce, has always been complicated.

“The last time I saw him was on December 23, 2003. I’d known my real identity for three years but I still went to see him,” he explains. “He was in his place of detention, drunk, and when I got there he started to reprimand me, saying he was there because of me. And then he threatened to shoot me when he got out of prison.”

Perez Roisinblit has come a long way since 2000, from anger and confusion to acceptance. Closure, though, is something he may not have until all 500 babies are found — and he discovers the final resting place of his parents.

“What I need, like any normal person, is to know where their remains are,” he says. “Then I can have a place where I can pay them my respects. And cry for them in peace.”

Shares