ARIHA, Syria — They aren't much talked about. And they are rarely talked to. But supporters of the Syrian government exist.

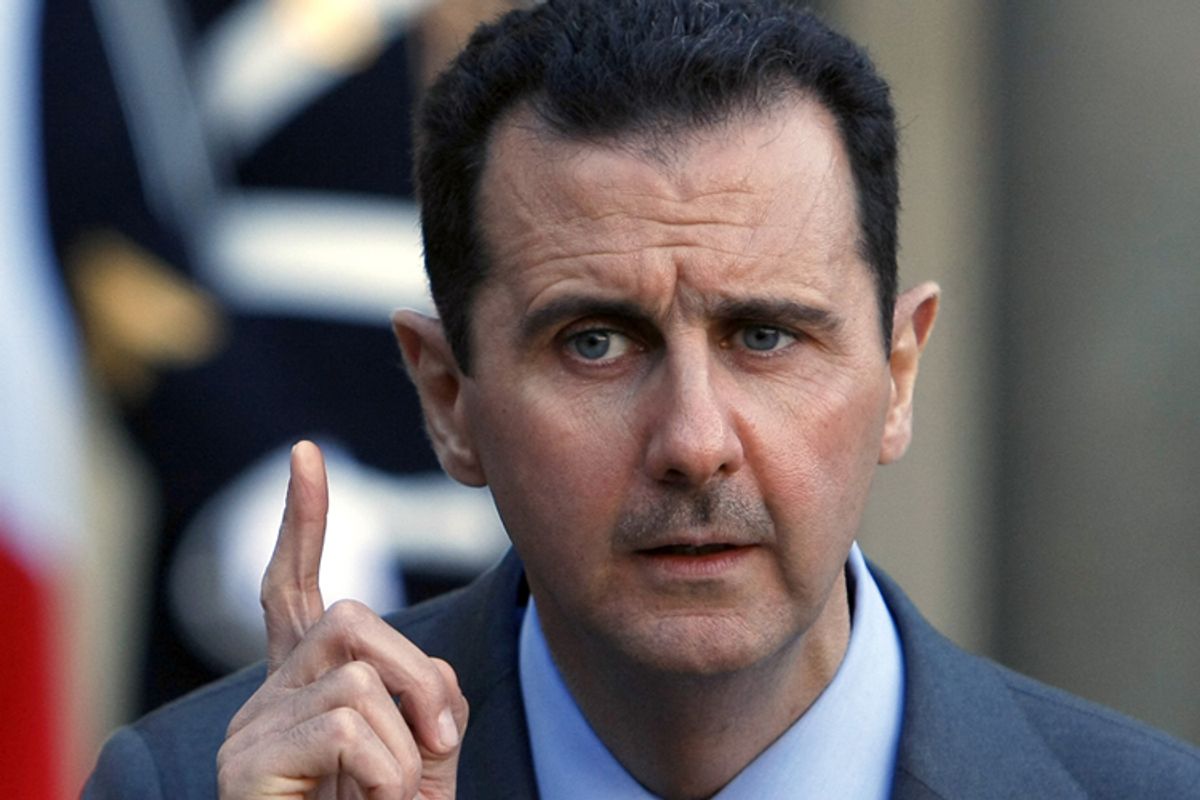

While President Bashar al-Assad's hold on power appears to be tenuous after rebels landed a fatal blow on his inner circle Wednesday, there are many families across the country that continue to support him and his administration.

In one family, which GlobalPost spent several days with here in northern Syria, four of the five members still back Assad. On one recent night they all sat, anxiously, watching a state television report about “insurgents” closing in on Damascus.

As they watched, the sound of chanting began to fill their living room. A small parade of anti-government protesters passed by.

“Those for the regime will meet your graves soon!” the crowd of mostly teenagers and children yelled, waving revolutionary flags, during their nightly parade through the dark streets of Ariha, a town now held by rebel forces.

The youngest daughter, who attends university in nearby Aleppo, spoke first. “Now that the army is gone, there is no one to stop them from killing us for speaking out,” she said.

“At the beginning I loved the idea of a revolution. We have a lot under Bashar — free medical care and quality education. But yes, I think we deserved more. But we’ve now gone backwards. This isn’t freedom. We’re being told how to think, how to dress, and threatened for having our own thoughts.”

Fearing retribution from rebel forces, the entire family asked to remain anonymous. Their ages have also been withheld to protect their identity.

They are not alone. Others in the city — who were all too scared to say much on the record — also said they supported Assad. The rebels that now control Ariha admitted that about a quarter of the people living here remained loyal to the regime.

By all accounts this is a typical Syrian family. No one works for the government. They have no connections to the army, and they do not belong to the Allawite minority that dominates the ruling elite. Like the majority of the rebels, they are Sunni.

But their opinions vary. The mother and daughters felt strongly that the rebels are to blame for the worst atrocities so far committed in Syria. The father blames both sides. And as for the son, he joined the revolution from the beginning and still participates regularly in protests.

He said his outspoken sisters are persuasive.

“From the first day, this revolution was violent,” said the oldest sister. She went on to describe the stone-throwing, destruction of public property and the physical violence against police that were prevalent during the very first protests last year.

She said her brother asked one boy early on why he destroyed the town’s only ATM, through which the majority of the city’s workers accessed their wages. The boy replied, “It belongs to the government, doesn’t it?”

"These are revolutionaries!" she said cynically.

The family said they had felt safe in Ariha when the army controlled the streets. While the opposition says army checkpoints were used to arrest the innocent, the family said the soldiers were friendly and their presence proved that the government was doing its best to maintain security.

The checkpoints are now manned by “fifth graders with guns,” said the oldest sister, referring to the rebels.

"Even if one person in this town is killed by an army bullet, it is the fault of the Free Syria Army," the younger sister said. "Every clash I have seen in this city, they always attack first. Of course the army must return fire if they are fired upon."

She said the Free Syrian Army uses "shabiha" as a perpetual scapegoat. The shabiha are a feared group of paid government thugs, civilians who activists say are responsible for large-scale slaughters, particularly of women and children.

"If they kill anyone, they just label them shabiha," she said dismissively. "They kidnap people for money and say they are shabiha."

The younger sister said the father of a school friend, who supported the revolution, was once kidnapped. The man had worked as a clerk in a government prison. After the family paid money to his captors, and he agreed to leave his job, he was released unharmed. Frustrated, she said her friend still supports the rebels.

“As a teacher, all kinds of authority has been taken from me,” said the older sister, who teaches English at a local primary school. She said students come and go as they please, claiming they want to join demonstrations. Boys chant offensive anti-Assad slogans in class.

“I am forced to condone this behavior or be labeled ‘anti-revolutionary,’” she said.

The family members went on to recount the numerous false reports and exaggerations that they said emerge daily.

The previous day GlobalPost witnessed an example. Pro-revolution television stations reported that the bodies of 20 men from Ariha, who had been imprisoned by the government, were found on the outskirts of town with their hands tied, throats cut and bodies mutilated.

Distraught families and rebel groups gathered at the town morgue, waiting for the arrival of the bodies. But they never came and soon news filtered down that the reporter had confused Ariha with a neighboring town. Eventually it was revealed that the whole report had been false, a fact that was never corrected by the local media.

The girls recalled attending the funeral of a friend who had died from cancer in the provincial capital of Idlib. They said that as journalists approached the scene, the crowd began to chant “as if she had been killed by government forces.”

Their mother added the account of a shopkeeper who had been caught in the crossfire of government and rebel clashes and was accidentally shot by the rebels themselves. He was buried the following day as a celebrated martyr.

“He was with them and they shot him by accident. How can they call him a martyr?” she asked. “They seem to think they can hand out passes for righteousness.”

As the regime continues to crumble, it is hard to believe there is any way Assad could remain in power. But families like these exist all over the country, and they are not fooled by propaganda from either side.

“I am not going to try to tell you about what is happening in another place like Homs or Damascus, although I have many friends that have told me what is really happening,” said the oldest girl, when asked about the reports of government massacres. “I am talking to you only about my town and what I have seen with my own eyes.”

Shares