The AP is out with an interesting piece predicting higher poverty rates last year. I know—sounds weird to be predicting a variable from 2011, but that’s how this works. It takes the Census Bureau time to collect and process the data on family incomes which are then compared to poverty thresholds based on family size, and the results are usually released in late summer of the following year.

In terms of the prediction for 2011, since researchers have a bunch of data for that year that correlates with poverty, we can usually get pretty close by now. My model’s finding the official rate rising from 15.1% in 2010 to 15.3% in 2011, which is about where others seem to be, as per the AP story.

There are two points I’d stress here: a) we are stuck with high poverty rates because we are stuck with a market failure that policymakers will not address, b) the official rates miss some important information on how the safety net has helped partially offset hardship for poor families.

First, market failure. Poverty rates go up for working people in recessions because–and the AP provides good examples—they lose jobs or, even if they keep their job, they lose hours. In fact, a highly significant variable in the prediction model is the growth in payrolls, a proxy for the above dynamics.

Now, payrolls have been growing, at least on the private sector side, but too slowly, and had Congress taken corrective action, say by passing the full American Jobs Act last year, payroll growth would be faster and poverty lower. If I simulate a million more jobs in 2011—a fair estimate of the jobs lost due to the austerity pivot—the model suggests that poverty would not have gone up last year.

In normal times, I’d be happy—well, maybe not “happy,” but at least willing—to engage in the usual debate about whether you can really attribute high poverty rates to the failure of markets or to Chuck-Murray-style failures of individuals to work harder, get and stay married, etc. But these are not normal times. As long as there’s so much slack in the economy in general and labor market in particular, that argument is especially disconnected from current reality.

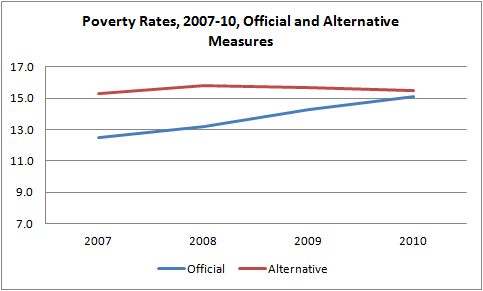

Second, the official rate, as should always be noted, fails to capture much of the safety net that’s in place to at least partially offset the economic pain of poverty. The figure below plots the official rate against an alternative measure which captures important measures that help low-income families, including the Earned Income Credit and the cash value of food stamps. The alternative measure equally importantly resets the poverty thresholds to reflect a more realistic view of what it means to be poor today.

Two things are notable from the figure. First, even when factoring in the benefits missed by the official rate, the alternative rates are higher. When you measure poverty more accurately, including adjusting the income thresholds to reflect living standards changes, there are more poor in the US than under the official measure.

Second, the safety net was very effective in preventing poverty from going up in the Great Recession. The expansion of income supports like refundable credits and other tax cuts, food stamps, health care, and rental assistance—all of which are absent from the official measure, prevented the alternative rate from rising relative to the official measure.

In other words, we have a safety net that is doing a decent job—better than many people realize—of offsetting some of the economic deprivation hitting our most vulnerable families when the economy slumps. But what we don’t have is anywhere near enough of an agenda to actually help folks like those in the AP piece who clearly want to work but can’t find the jobs or the hours they need.

More precisely, we actually have a decent agenda–useful policies to help low- and middle-income folks in both the near and longer term. In the Recovery Act, subsidized jobs programs for low-income workers had a big bang for the buck, and Pell Grants, Head Start, and even the EITC can be viewed as programs that have a positive long-term impact on the employment and earnings of kids from families with lower incomes. What we lack are the politics to sustain and expand these pro-work ideas to meet the needs of the poor.

The poverty debate, going back to the Poor Laws in 17th Century England, has always centered around society’s expectations that “able-bodied” citizens should work. We most recently revisited the ancient debate with our own welfare-to-work debate in the 1990s. But whichever side you’re on, it simply makes no sense to assume people can pull themselves and their families out of hardship when the jobs aren’t there.

Remember that point when the poverty numbers come out for 2011, and people start squawking about personal responsibility and the “culture of poverty.” It’s true: there are people shirking their responsibilities right now, but they’re not the poor. They’re the policymakers who refuse to help them get back to work.