![]() Like Maud, I fell for text adventure games in the 1980s. They were exciting precisely because you couldn’t detect the boundaries and limitations of the world they constructed, and because it felt like you could navigate that world at will. If you turned left, you might discover a castle, while turning right would lead to a dark and menacing forest. Your choice!

Like Maud, I fell for text adventure games in the 1980s. They were exciting precisely because you couldn’t detect the boundaries and limitations of the world they constructed, and because it felt like you could navigate that world at will. If you turned left, you might discover a castle, while turning right would lead to a dark and menacing forest. Your choice!

But the earliest adventure games, like many of their graphical descendants, turned out to be a lot more constrained than they at first appeared. You could do “anything,” but somehow you always wound up looking for a crowbar or a box of matches so that you could execute some banal task that would ultimately give you access to another bit of imaginary space in which you’d have to perform yet another inane job. These games are fun in the way any puzzle can be fun, but they aren’t really stories. The best of the bunch, the game Myst and its sequels, could be gorgeous and absorbing, but not ever truly moving the way a novel or dramatic work can be. It was once fashionable to claim that games like Myst pointed to the future of storytelling, but the rudimentary stories offered by the vast majority of the genre are less compelling than the average folktale, let alone a play or film.

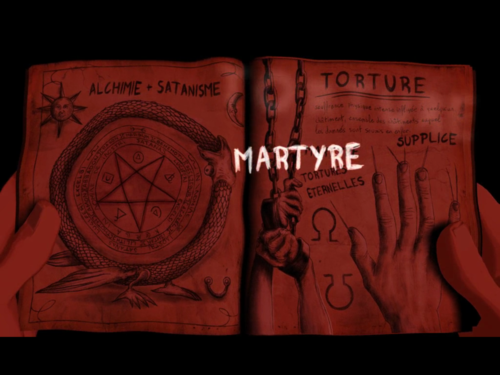

For that reason, Yesterday by Pendulo Studios is an intriguing departure. Yes, there’s a lot of rummaging around for pen knives and oil cans in order to fix machinery or unearth hidden keys, but the game is more story than puzzles, and the story itself is a gruesomely baroque concoction of satanic cults, renegade academics, mad preachers, gnomic martial arts masters, serial killers, reincarnation and a sinister billionaire.

The central narrative of Yesterday is like the plot of an adequate B-movie in the supernatural thriller genre. This may sound like faint praise, but this is the only game I’ve ever played in which the plot achieves that much substance. There’s a prologue involving a volunteer for a homeless center who falls into the clutches of religious fanatics living in a deserted subway station, then the action resolves around John Yesterday, a private detective with total amnesia striving to recover memories of his past after an apparent suicide attempt. Amnesia is a fairly common affliction for video game protagonists; the player doesn’t know who the character is, and memory loss puts the character himself in the same boat. But Yesterday is unusual in keeping the purpose of the game firmly focused on reconstructing the narrative of John’s life.

The characters, including John himself, are the robotic animated figures typical of many computer games, and the quality of the animation here is not especially high. (Particularly unsettling is the rendering of people’s mouths as they speak — they all seem to suffer from a surfeit of teeth.) This is, of course, a big problem in all such games, even those whose animation is much more realistic; however accomplished, these drawings will never be as emotionally engaging as a real actor’s face, although the player’s investment in scoring and achieving other goals will usually compensates for that.

A good test of the strength of any game’s narrative is to ask whether it would be at all interesting if the gameplay and goals were subtracted — if all the fighting/killing were removed, or all of the puzzles. What makes Yesterday exceptional lies in the answer to that question. To my surprise, I found myself genuinely curious about the mystery of John’s identity and how he lost it while engaged in some highly dubious research. This is largely due to the game’s ambiguous villain, Henry White, who looks like an over-dentated Ron Howard in the “Happy Days” era and whose true motives remain enigmatic up to the end.

Storytelling and gameplay, however, are almost always at odds with each other, if for no other reason that that a game hinges on the player’s volition while stories require the audience to surrender to the storyteller’s vision. With Yesterday, the tasks demanded to move the narrative forward feel like trivial, mildly annoying obstacles that don’t have much relevance to the player’s real concern: getting to the bottom of John Yesterday’s dilemma and figuring out what Henry is up to. This sensation isn’t helped by some fairly awkward game mechanics.

Yesterday offers a choice of endings, although there really isn’t that much difference among them. (Some are more gruesome than others, but the game overall is not for the squeamish.) That feels right; one of the great satisfactions offered by a good story is the feeling that its conclusion is both unpredictable and, when revealed, inevitable.

— Laura Miller

Shares