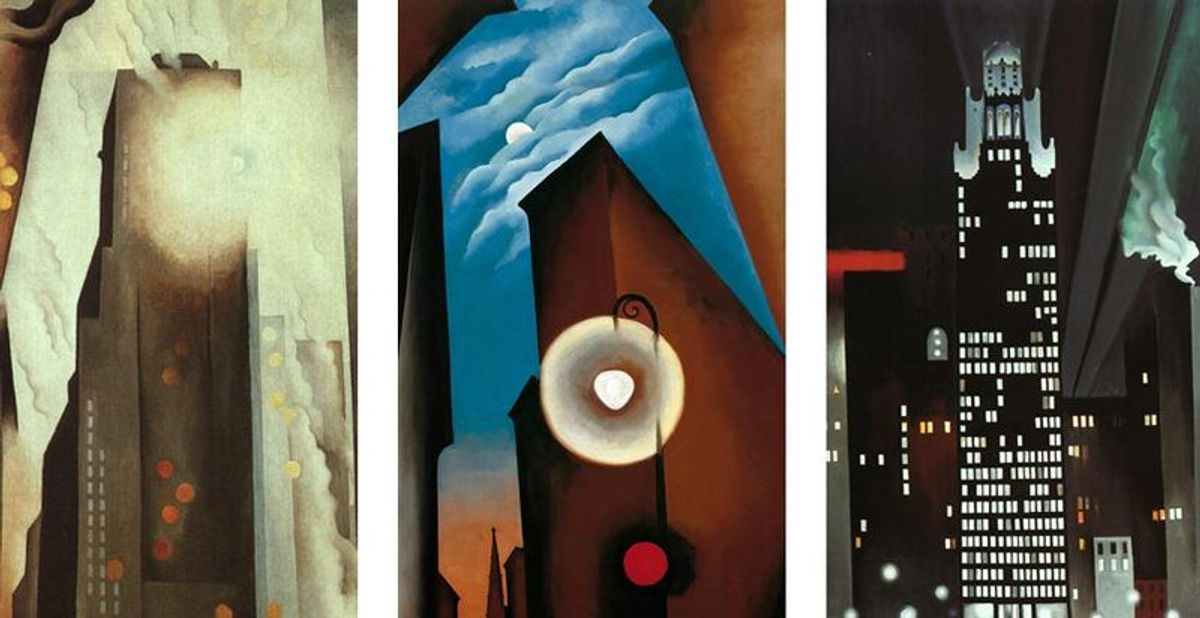

Most well known for her portraits of erotic flowers and looming skulls, Georgia O'Keeffe was also haunted by cityscapes. She moved to New York City in 1918 to immerse herself in her art full-time at the invitation of Alfred Stieglitz, the gallery owner who supported her and would become her husband. Stieglitz held salons in a brownstone on 65th Street, where O'Keeffe was as likely to run into William Carlos Williams as Arthur Dove (though she didn't care for small talk with any guest). After her marriage to Stieglitz, the couple moved into the Shelton Hotel at 49th and Lexington. In 1925, the year they took up the new address, forty-five skyscrapers were constructed in New York, the most in one year. They lived in an apartment on the thirtieth floor of the Shelton for twelve years. O'Keeffe often painted what she saw from the window. In the first four years, she created thirty skyscraper paintings, according to the Minneapolis Institute of Arts.

[caption id="" align="alignnone" width="434" caption=""East River From the Shelton" (1926)"][/caption]

We could do worse then spend an afternoon looking at how O'Keeffe saw her city.

What most strikes me is how these paintings are empty of people, but crowded with shape, color, and shadow. They are portraits of corners. Through the angles and edges, through their overwhelming hush, they provoke the fantastic.

[caption id="" align="alignnone" width="320" caption=""Street, New York I" (1926)"][/caption]

When I write that I feel acutely aware of the lack of people in O'Keeffe's city-portraits, I include the protagonist. By virtue of the vantage of these paintings, there is a gesture towards some first-person perspective: it looks like we are on ground level, looking up, or from a high window, looking down. But that is all there is: a gesture. From there, the perspective on the city is seeped in ambivalence. Too plain and simple to call it romantic. Too grand to call it disgusted or satiric. The paintings evoke a particular eye, but then resists a point-of-view.

[caption id="" align="alignnone" width="344" caption=""Lake George Window" (1929)"][/caption]

Shares