On July 15, 1972, David Bowie and his band performed at Friars, a club held inside the assembly hall in the Buckinghamshire town of Aylesbury, for the third time in less than a year. On his previous visits, Bowie had been an amiable, approachable figure, happy to chat to audience members after the show as a friend rather than an icon. Now Bowie was accompanied by a busload of journalists flown in by MainMan from America; flanked by security guards; preceded onto the stage by strobe lights and Walter Carlos’s theme from the movie Clockwork Orange; and then kept safely apart from the same fans whom he’d greeted warmly a few months earlier. They wrote distressed letters to the pop press: what has happened to David Bowie?

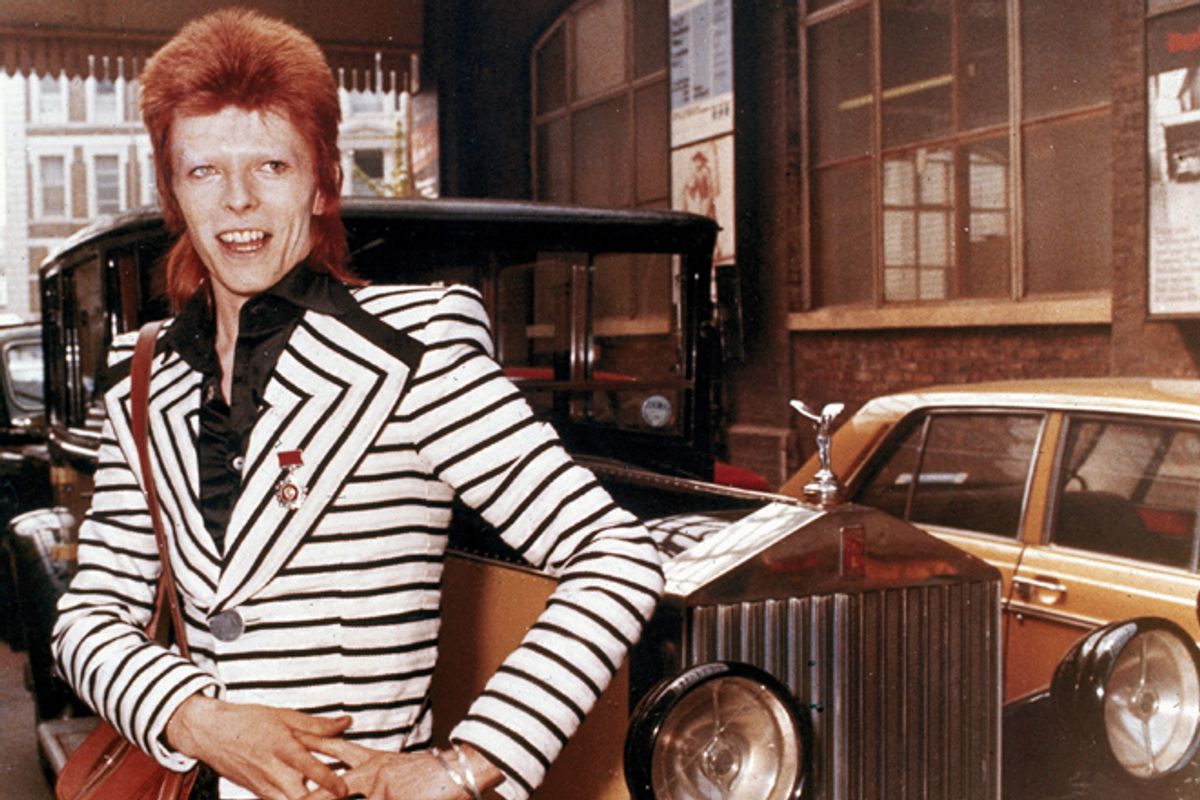

It was not Bowie who appeared at Friars that night, however, but Ziggy Stardust: the conceptual art project who had become a rock’n’roll star. “I’m continually aware that I’m an actor portraying stories,” Bowie admitted the following day, “and that’s the way I wish to take my performance.” Ziggy was the guise he had chosen to adopt, “for a couple of months.” In an unguarded moment, he could confess that impersonating Ziggy had imposed a bizarre sense of dissociation from his “real” self: “It’s a continual fantasy. . . . I’m very rarely David Jones any more. I think I’ve forgotten who David Jones is.”

Seven weeks earlier, when The Rise and Fall of Ziggy Stardust and the Spiders from Mars LP was released, David Jones/Bowie was not a star—not in the way that Marc Bolan was, or Alice Cooper. Main-Man hyped the record as if he had already achieved that status, boasting that his previous album, Hunky Dory, was “now high in the US charts”—which was true, as long as you regarded a placing of No. 185 as “high.” Bowie and his management had effectively decided to let Hunky Dory succeed or fail by itself, and to focus their energy on the Ziggy concept. But six weeks after its release, the “Starman” single, which was intended to stir up anticipation for the album, had still not charted. The success of Ziggy, and with it Bowie’s entire credibility as a

pop performer, was in the balance.

The initial response to the album was lukewarm. Nick Kent in Oz magazine complained that Bowie was attempting to “hype himself as something he isn’t.” The rock paper Sounds noted that the record “could have been the work of a competent plagiarist . . . a lot of it sounds as if he didn’t work on the ideas as much as he could have done.” This was the verdict of reviewers who had raved over the dense, philosophical songs on Bowie’s earlier albums, and could not relate to the apparently simplistic rock mythology of Ziggy Stardust. By contrast, Michael Watts of Melody Maker—to whom Bowie had made his “I’m gay” boast earlier in the year—immediately under-stood the singer’s intentions: the album, he wrote, “suggests the ascent and decline of a big rock figure, but leaves the listener to fill in his own details, and in the process he’s also referring obliquely to his own role as a rock star and sending it up.”

The challenge for journalists who believed passionately in the authenticity of their idols was to accept that distance, irony, and fiction could be acceptable methods of confronting the star-making machinery of rock. They had balked at Columbia Records’ publicity campaign for “The Rock Revolutionaries,” in which a multinational media corporation attempted to use the symbolism of “revolution”—the radical touchstone of the age for Western youth—as a means of selling plastic product. Now Bowie was expecting them to deal with an artist who was quite blatantly using rock iconography to sell himself, and the illusion of stardom, as commodities. (“I’m very much a conglomerate figure,” Bowie admitted in 1972. “It’s a visual exercise in being a parasite.” He could not be accused of covering his tracks.)

Only in retrospect* would the audacity of Bowie’s maneuvers be appreciated and understood. In June 1972, several emblematic TV appearances (notably on Top of the Pops) combined with the undeniable commercial appeal of “Starman” [60] to create exactly the degree of stardom for Ziggy Stardust that Bowie had envisaged. The audience for these records had not graduated through the dense lyrical explorations of Bowie’s beliefs and fantasies that made up the David Bowie [1969 edition], The Man Who Sold the World, and Hunky Dory LPs. If they knew Bowie at all, it was as the avowed bisexual who had written “Oh! You Pretty Things” [30]. Analysis of the shifting viewpoints and incomplete narrative of the Ziggy Stardust album could come later. Before then, the British pop audience—and especially those among them who were confused about their own identities, sexual or otherwise—welcomed the arrival of a homegrown performer as daring and provocative as Alice Cooper, as tuneful as the Beatles, and more mysterious than Marc Bolan could ever hope to be.

By the time of his Rainbow concerts in August, where he presented a theatrical concept featuring a mime troupe (the Astronettes) led by his onetime mentor Lindsay Kemp, Bowie was stardom personified, his concept brought to ecstatic, multicolored life. But the intensity of his personification was already beginning to show. When he arrived in America the following month, he told Newsweek magazine that “I’m not what I’m supposed to be. What are people buying? I adopted Ziggy onstage, and now I feel more and more like this monster and less and less like David Bowie.” His star had become a straitjacket, one that he would struggle to slough off for the next year and beyond.

Excerpt from "The Man Who Sold the World," copyright 2012 by Peter Doggett. Courtesy of HarperCollins.

Shares