Here are the stories of two Olympic decathletes.

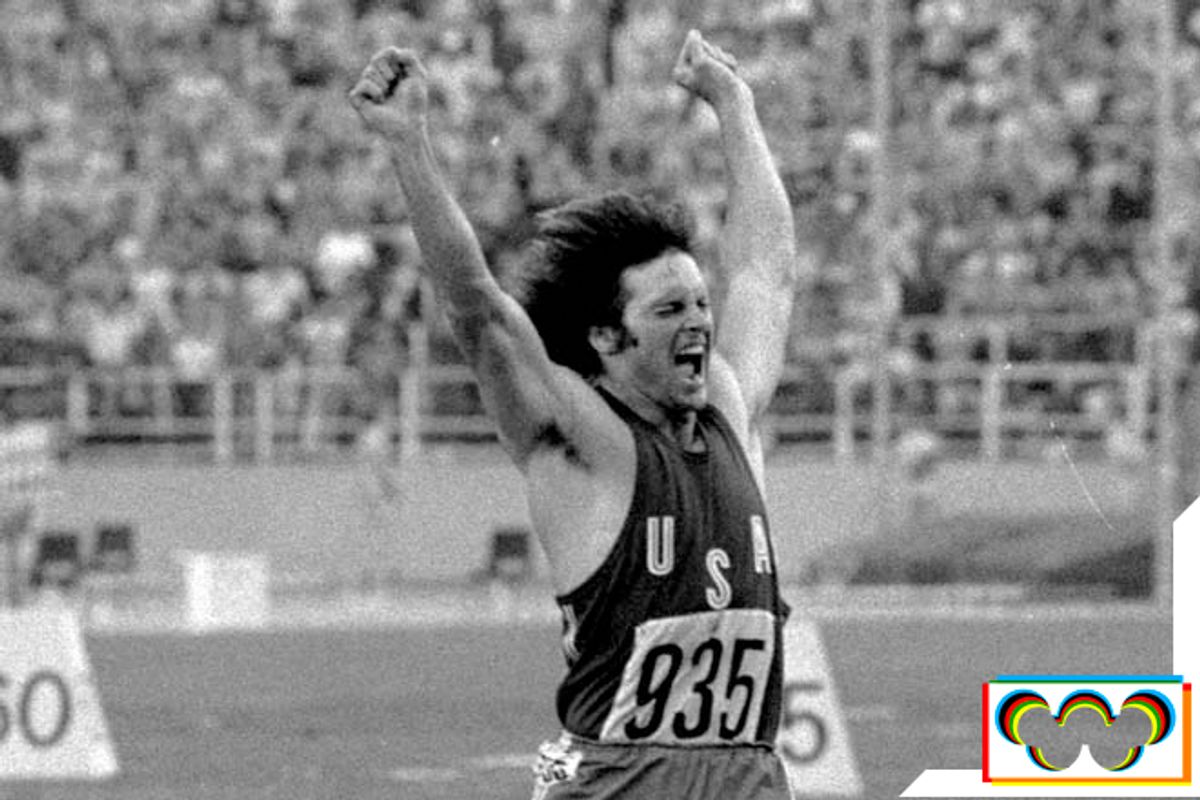

Bruce Jenner won the gold medal at the 1976 Montreal Games. His bicentennial triumph earned him a celebrity of the purest sort: It has persisted not only after he lost the ability to do what made him famous, but after the point when most people remember how he became famous.

In the half-decade after Montreal, Jenner wore a male Daisy Duke in the Village People biopic "Can’t Stop the Music," got a nose job that put him at No. 1 on a list of Men Who Look Like Old Lesbians, and replaced Erik Estrada on "CHiPs." Today, he’s best known as the stepdad on "Keeping Up With the Kardashians," which is mostly watched by people born after 1976. This is a man whose fame is so durable he’s passed it on to children who don’t even belong to him.

“Being a celebrity is a business,” Jenner told Esquire magazine. “That’s how you have to look at this, and by that measure, this is a very successful business.”

Then there’s Bryan Clay. After Clay won the decathlon in Beijing, his manager predicted the victory would be worth $20 million in endorsements and speaking fees. Half-black, half-Asian, a family man with three children, he should have been the perfect 21st century pitchman. Three years later, he was dropped by sponsor Nike. Clay failed to make this year’s Olympic team, so his marketability is pretty much dead.

Why is Jenner one of the most famous Olympians ever, while Clay -- who also won a silver in Athens, making him the more decorated athlete -- is headed for the ash heap of celebrity? It was all about timing. Jenner was a Cold Warrior, sent out to engage the Communists in single combat at Stade Olympique. For most of Olympic history, the United States had dominated the decathlon, winning three-quarters of the gold medals, going back to Jim Thorpe. The decathlon was considered an all-American event, because it rewarded the most well-rounded athlete. Then, in 1972, the Soviet Union’s Mykola Avilov won the gold, breaking (American) Bill Toomey’s world record. It was Sputnik all over again.

During the Cold War, the Olympics were politics by other means. The East was convinced that athletic success proved the superiority of socialism. The West was convinced the Commies were cheating by paying their athletes to train -- thus violating Olympic rules on amateurism -- and injecting them with steroids. (The only place East Germany still exists is in the women’s track and field record book.) By snatching back the decathlon from the Soviets, Jenner inspired a spasm of anti-Soviet patriotism equaled only by the 1980 Olympic hockey team’s Miracle on Ice. Since there was one of him, and 20 of them, he got a Wheaties box to himself.

Jenner was part of a generation of American Olympians that also included Frank Shorter, Mark Spitz, Carl Lewis, Mary Lou Retton, Jackie Joyner-Kersee and Greg Louganis. Since we ended our beef with the Communists, only Michael Phelps is in their league.

The Olympics have never been more popular than they were in the 1970s, when the U.S.-USSR rivalry combined with ABC’s living color to turn them into a televised track meet between Good and Evil. (Bob Costas can host the games until his hair turns naturally brown again, but he’ll never be able to match Jim McKay’s historicizing.) The 1972 Munich games and the Montreal games each averaged TV ratings in the low 20s. The Olympics were never more politicized than they were in the 1970s, either. During the second half of the Cold War, every Olympics became a platform. In 1968, 200-meter medal winners Tommie Smith and John Carlos raised their fists in a black power salute. In 1972, Palestinian terrorists killed seven Israeli athletes. In 1976, 28 African nations boycotted because the International Olympic Committee refused to ban New Zealand for playing rugby against South Africa. In 1980, the U.S. boycotted the Moscow Olympics over the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan. In 1984, the USSR boycotted the Los Angeles Olympics in retaliation for the U.S. boycott. And in 1988, North Korea refused to send a team to Seoul.

(If you want to go even further back, the reason we remember Jesse Owens’ four gold medals at the 1936 Berlin Games is because he pissed on Adolf Hitler’s philosophy of Aryan superiority.)

Because the Olympics were so politicized, they had a meaning deeper than individual achievement, deeper even than the team sport rivalries that excited sports fans during the other three years of the athletic calendar. They were an opportunity to cheer for our way of life, against athletes representing nations who threatened it. (In 1982, my high school English teacher lectured us, “If there is an evil in this world, it’s Communism.”) It wasn’t just Bruce Jenner winning the decathlon. It wasn’t even just America winning. It was freedom winning. Also, for the first time since the War of 1812, Americans got to feel like underdogs in an international event. That made great TV.

When the Berlin Wall collapsed, so did Olympic TV ratings. The 2004 Athens games did a 7.0 -- a third of the 1970s’ games. Which is a shame, because without political implications, the Olympics are a better athletic competition. There’s less cheating, now that the Eastern Bloc drug dispensaries have been shut down. (Although by the 1980s, steroid use was a bilateral offense. Canada’s Ben Johnson lost a gold medal for doping, and there’s likely a good pharmaceutical explanation for why no one has come close to the 100-meter world record Florence Griffith-Joyner set in 1988.) There are no more boycotts: A record 204 countries competed in Beijing. And there’s less nationalism. For all the Coca-Cola tie-ins, the 1996 Atlanta games still didn’t have the “America, Fuck Yeah!” feeling of Los Angeles in 1984.

The Cold War’s end has also allowed third-world nations to become Olympic superpowers. In 1976, the Eastern Bloc won over half the medals. In 2008, those same nations won less than a quarter. Now, the best athletic rivalries have nothing to do with geopolitical competition. Kenya vs. Ethiopia in distance running. Hungary vs. Serbia in water polo. Russia vs. Iran in wrestling. The U.S. vs. Australia in swimming. The U.S. vs. Jamaica in sprinting. But Americans don’t get as excited about beating Australians and Jamaicans as we did about beating Russians. Because we don’t hate them. Which is what the politicized Olympics were all about.

The Olympics are a showcase of niche sports. Swimming, pole vaulting, archery and white-water kayaking are contested by individuals, not teams. In sports, the real product is winning. The team wins, the fans experience a boost of superiority and self-esteem. The Olympics no longer have much of that to offer Americans, except during the basketball tournament. There is a bright side, however: In 2040, Michael Phelps probably won’t be a bit player on a reality TV show.

Shares