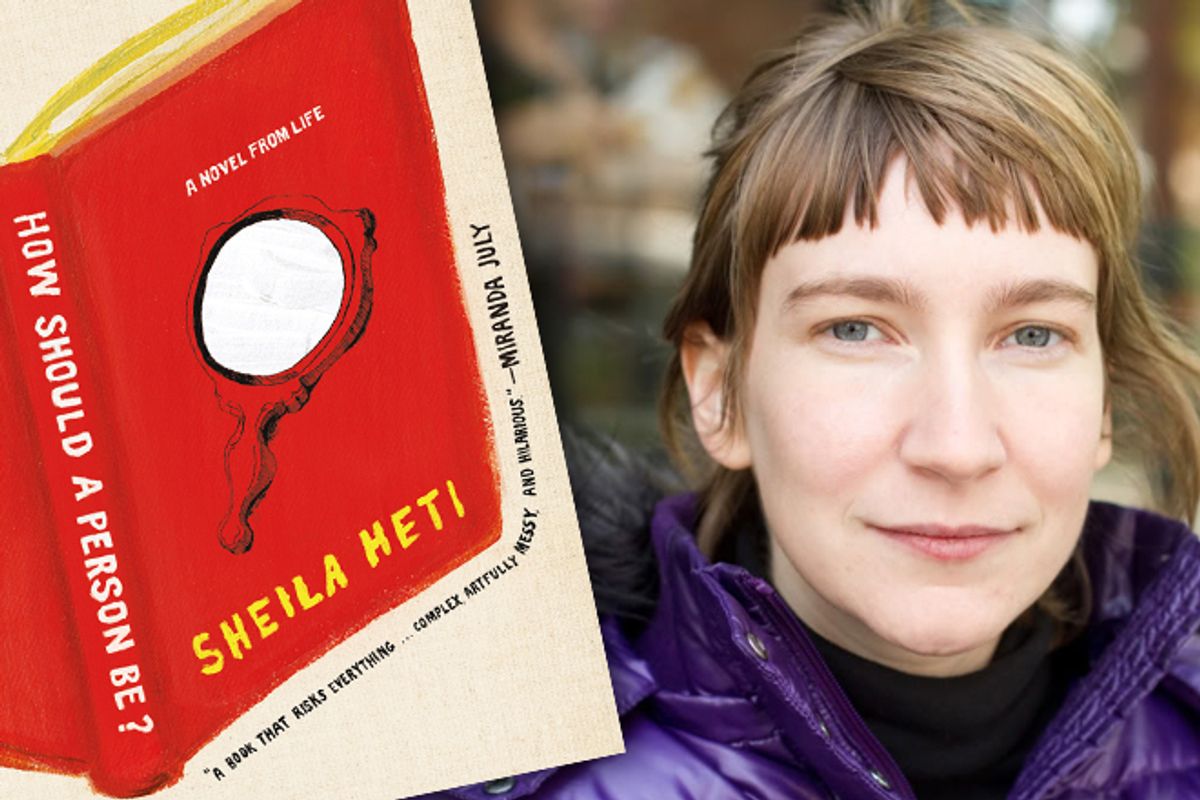

Last year I ordered, from Canada, for a whopping 40 American dollars, a copy of Sheila Heti’s “How Should a Person Be?” Why would I do such a thing: Pay 40 dollars instead of waiting nine months and paying 10?

My friend had trained up the Hudson for a visit. We talked and ate and hung out and took my kid to the fire truck museum and bribed him with Elmo on the iPhone while we spent an hour in the best vintage shop. I told her about the fiction-thing I’m working on, about the impossibilities of female friendship. She told me about the Heti book. And as we sat on my couch under a new, still hopeful ficus tree, smoking a joint, I felt convinced that female friendship is perhaps not so difficult after all. I needed to read the Heti. Maybe my novel would have a happy ending.

“HSAPB” was finally published in the U.S. in June (see this link for the long story of how and why publishers can be so terrifically dumb), and to a rapturous reception. It’s a literary home run, and rightly so. All the smart girls are talking about it, which is exciting, because one doesn’t come across books like this very often. It’s about women who fall in love with each other’s minds. It’s about women’s efforts at becoming creatively liberated. It’s a big old breath of fresh air. It’s candid and deadpan and plays with the whole idea of a novel in interesting ways. What is a novel? Where do novels come from?

But meta-conceits about fiction aside, the girl/friend problem is front-and-center. Sheila (or “Sheila”) is obsessed with the brilliant Margeaux, a vibrant and honest painter. Sheila’s a rather late bloomer, in the thrall of her first ever girl/friend lust: “I realized I’d never had a woman... I supposed I didn’t trust them. What was a woman for? Two women was an alchemy I did not understand.”

Friendships are unbalanced by nature. This can be OK if the balance shifts and evolves, and very not OK if not. Sheila’s the mildly irritating chick you can’t quite trust. The gently exploitative one who subtly copies everything you do. She’s not very open or warm, but somewhere in her heart (and prose) there’s a detectable and lovely bit of yearning. I’ve had friends like her. I’ve been her. So it goes.

Anyway, the book got me hopped up, and I wrote a Rumpus Letter in the Mail (which sends actual letters, on paper, through the postal service) in which I mentioned “HSAPB,” talked about disliking reviewing in general, and called Heti a bitch for good measure. I felt free because the letter wasn’t going online and because one has to have at least the illusion that one is free otherwise one cannot write.

But it’s been nagging at me. You can’t just go around calling people bitches. Why the need to call this smart writer a bitch? 1. I’m a bitch. 2. I imagine her to be part of an imagined coterie of imagined-to-be-important writers and artists from which I am imaginarily rejected. 3. Her book lacked heart. 4. I need to believe it’s possible for a novel to be both fiercely intelligent and self-aware and also full-to-the-brim of heart. 5. We’re reclaiming it. Am I right, kikes? 6. I didn’t and still don’t feel like writing a proper review. I have a three year old and a rocky marriage and a 200-year-old house and a weedy garden and a stubborn novel of my own and am trying to meditate at least a little bit every single day so I don’t become one of those women who passive-aggressively over shares on Facebook and wakes up in the morning with her jaw clenched, OK?

(And this is why people write criticism in general, isn’t it? To call attention to themselves? Why play at neutrality? HEY! I’M A WRITER TOO!!)

Like Sheila, I’ve long searched for a girl to call my own. I’ve gone through so many. So many! This one’s too uptight, that one wants to sleepwalk through life, this one’s cold, that one is obsessed with men to the exclusion of everything else. I wrecked that one. This one’s not interested in me. (“I could never fault someone for not wanting to be my friend,” writes Margeaux at one point in the novel, when she feels snubbed by Sheila.) That one’s not interested in accommodating my kid. This one’s paranoid her husband wants to have sex with me. That one’s competitive. This one’s, like, pathologically competitive. That one’s a bore. This one’s absurdly flighty. About a dozen live too far away. This one’s got a hell of a lot of nervous energy. That one’s materialistic. This one’s insecurity gets the best of everything. That one’s firmly in the grip of every health problem only rich white women seem to have.

I’m a flawed woman. Too soft, too eager, to harsh, too dorky. Too smart, too lazy. Fickle. Clumsy. Ridiculous. Depressed. I unabashedly love the Indigo Girls. My thighs are grotesquely hairy. I sometimes pretend Lindy West on Jezebel is my best friend. I like to talk about my period. Trying on clothes relaxes me. I hate Adele.

My once-best friend broke up with me in the middle of a New Years Eve party at my apartment. “You are SUCH A FUCKING BITCH!” she screamed. It was about a third party, a dull girl I made fun of a lot. My best friend sometimes made fun of the dullard and sometimes defended her fiercely. The party went silent. We both burst into tears and pretty much never spoke again until she emailed me six years later. “My father died tonight,” she wrote. I was shocked she’d written. I was glad she’d written. I had no idea how to respond. I managed something lame about being sorry for her loss. Soon thereafter we began a benign acquaintance that I find almost a bigger bummer than pretending she fell off the face of the earth entirely. I still miss that cunt. We had coffee six months ago in Philadelphia. She brought her husband, for whom I did not much care. But her eyes still sparkled and I could see her in there and it was great, seeing her in there for a few minutes. She’s pregnant now. I’ll always love her. Screw her.

Where is my girl? The one with whom I can just be quiet and un-self-conscious? You don’t have a sister, you wander through life and literature looking for your sister. “HSAPB”’s Sheila is not her. Too detached. Too distractingly self-conscious. Cold. Self-serious as can be. Alas.

Obviously, the whole “I would/nt want to be friends with this author/protaganist” thing is bullshit. It’s how thick readers avoid unpleasantness and complexity and darkness. (Anyway Heti’s all: “Yeah, well, I wouldn’t want to be friends with you either, bitch.”) (Or probably a more Don Draper-esque “I don’t think about you at all.”)

But I don’t read with my head, I read with my stomach. This is not a review. This is how I feel.

That said, calling Heti (or “Heti”) a bitch doesn’t really do her justice. “HSAPB” is smart as hell, and funny and honest and important. Not important like: will ensure clean water for all humanity. Important like: here is a woman – a pathologically, chillingly self-aware 21st century female person – not in hiding. I bow to that.

And I mean, I get it! No shit she’s a bitch! It takes cold hard ambition to succeed as an artist (also to succeed as a woman, since femaleness is almost entirely artifice in the first place). Double bitch: artist bitch, female bitch. Ambition is not very “feminine” so you frequently see the unpleasant alternative: lady writers doing the disgusting drippy-syrup act. The Golly Gee Little Old Me self-promotion business.

“If there’s one quality I hate in a woman, it’s modesty,” writes Emily Carter in the stellar “Glory Goes and Gets Some”, an early Emily Books pick. “Besides making me, with my trombone mouth, feel vaguely uncouth, I think it’s a chickenshit response to the demands of the marketplace, or the universe, not that I can tell them apart.”

And wait, at the same time I’m reading Rebecca Brown’s stunning and spare AIDS hospice novel “Gifts of the Body,” and Emily Rapp on Salon, putting things in perspective. No one’s child is dying of Tay-Sachs, here. We’re hair-splitting various modes of privilege. We’re staring at screens and taking self-portraits and rearranging our profiles. Nothing’s actually at stake! Time’s a-wasting.

And then there’s poet Ariana Reines across the train aisle one day in the spring; we’re both on our way to her reading in Hudson and there’s no one else around and she is so compelling, she is so magnetic and amazing I feel like a stupid child. I introduce myself, trembling, and she is beautiful that night and we have dinner and I just want to listen to her talk, I want to see the world with her, I want to handcuff myself to her so we can inhabit each other's lives for a while. “Coeur De Lion” is the most crazy excellent book, I reread it and reread it: “I think you are/ a kind of rebel, the kind that I like/ The kind who is not afraid/ of what he wants/ And who lives in the confusion of it/ By reading.”

I used to be terrified of being a lesbian. The fierce homophobia in my family, the intensity of relation I always want with other women. The way I yearn for them, want to study them and be physically close to them and memorize them and learn from them and emulate them and show myself to them. Just be very, very near to them. Wanting, at the very least, to wrap myself around particular women, touch them. The comfort I’d find there. Wanting to kiss particular women. An acquaintance whose mouth is so transfixing I’d like to spend a few days alone with her, exploring it. (God, I hope there’s room for that in my marriage.)

I wrote Dear Sugar a pair of letters once. She answered; I was touched. She’s the closest thing we literary douche-bags have to a religious leader. I thought, more or less: I would very much like to be her friend. Then I heard Sugar was Cheryl Strayed, and the magic dissipated. Just another flawed and regular woman, fetishized and lionized beyond reality. I devoured “Wild,” and although I loved its heart, its soul, its insistence that women must not live lives based in fear, it must be said that its prose, its sentences, were not super duper airtight artful inspiring awesome.

(“But I guess/ Fetishizing sentences/ Is no fair. They’re/ Not you. They/ Are in your/ Vicinity./ Maybe a human will/ Always be more/ Distressing and absolute/ Then what he/ Makes./ I hope/ So,” says Reines.)

No writer can be all things to all readers. If I want the pleasure and remove and aesthetic pleasure of shrewd, clever irony, I can always hang with Heti. From sweet sugarplum fairy godmother Strayed I get some news I can use. Sometimes you get so sick of sweetheart nice girls that you run into the arms of the smart, mean ones, know what I mean? And the mean ones sure as hell ain’t gonna sit with you while you learn how to breastfeed your kid.

I send an early version of these thoughts to an older writer I like and admire. She congratulates me on my “fierceness” and goes on to say it seems to me your anger at women and women who write is conflated, and to be honest -- the way you want others to be -- confused... I think they are two different angers.

It’s true, I replied. I always get my angers confused. Confused anger is the starting point of narrative. Try and separate out your angers and you’ll find you begin to tell stories. When the angers remain stubbornly twisted, irrational, unfair, unsubstantiated ... well, the story is the better for it. The best stories are hopeless, tangled, and real. They tend to not be bestsellers, unfortunately.

Another fiftyish woman writer who’s never been reviewed in the Times (five truly serious exceptional funny well-published books over the course of two decades, ignored) tells me you have to review if you hope to be reviewed. What a terrific drag, to have to figure out how the game works, then set about playing it that way. I don’t get the art of reviewing, the occupation of it. The networking and the niceness and/or bitchiness called for. And who needs plot summary? You bring yourself to a book, your petty biases, your moods. To pretend otherwise seems a waste of time. To debate the relative merits of creative work in the first place seems a waste of time. There are not enough hours in the day to be polite about shortcomings, to curry favor with other writers so that they will give you a hand when it’s your turn, save you a seat at dinner at the writers’ colony.

I mean: love the things you love! Loan them to your friends! Let them inspire you! Ignore the things that suck. Ignore them very hard. They mean less than nothing, even if they are endorsed by ass-lickers. Especially when they are endorsed by ass-lickers.

I’m sorry I called Sheila Heti a bitch. It’s not nice to go around calling people bitches. Also it’s a kind of career suicide. And when I called Heti a bitch I suppose I was doing what I thought only men do: call women they don’t want to fuck bitches. Or maybe want to fuck very badly indeed but don’t remotely have the temerity to swagger toward.

I’ll have to eat dinner all by my lonesome at the writers’ colony.

You can usually tell when a book or film or music by a woman is going to be worthwhile: Insecure women loathe it extensively. (See also: the work of Lena Dunham #dontgetmestarted) Yesterday some magazine lady I used to know was shitting all over Amy Sohn, which is how I know that Sohn’s new book, a seemingly charming surface-y harmless soap about messed-up Brooklyn moms, is probably going to be a great big pile of fun. Not everything has to be serious. Not everything has to be artful. But everything does have to be honest. We have limited time here, bitches.

Oh, and then there’s the positively insane, nearly forgotten novelist Kate Braverman! We’ll have to discuss Kate Braverman sometime. The one who recommended good old Kate Braverman lives in Boulder and is a kick-ass writer and our menstrual cycles are aligned and we’re both mega-fucked about relationships and so for a week each month we sit on the phone for hours complaining about the men and threatening to leave them, just bitching each others ears off. It’s kind of excellent and kind of terrible, our parallel spirals. Comforting, exhausting. We rarely talk in good moods. Everything’s a stage play.

That night on my couch under the still-hopeful ficus I took a video of my Heti-recommending girl. I intended to take a photo, but goofed. It’s only about 11 seconds long. She holds the joint. She is very beautiful but if you told her that she’d be uncomfortable. She’s tough and smart and does not seem to like it when I touch her.

You know how people used to have, like, salons? she asks, calling forth an image of women hanging out beneath enormous hair dryers, having their hair set for the week, telling secrets and laughing.

Yeah, I say, knowing what she means. Literary salons. Community! That elusive thing we all yearn for and so seldom seem to get, because being nice to everyone all the time isn’t honest and you just wind up kind of hating everyone eventually if you’re not honest.

Maybe those were all just super annoying, too. Then she did this magnificent, adorable crack-up, but I stopped the video too soon.

Shares