With backpack slung behind, headlamp set in place and gloves on hand, Steve Duncan heads down a set of subway stairs. He makes his way to an abandoned station, under a manhole and beyond the city lights of a bridge. His words of warning: “Don’t hit the third rail, don’t get run over by trains, watch for motion detectors and don’t be seen.”

Duncan calls himself an urban explorer. The 33-year-old Maryland native has lived in New York City since 1996, barring two years spent studying in Los Angeles. He is currently a student at City University of New York Graduate Center, working on a Ph.D. in Urban Studies, a discipline he knows as “Sewerology.” Duncan is also a researcher with CUNY’s Institute for Sustainable Cities and a freelance photographer.

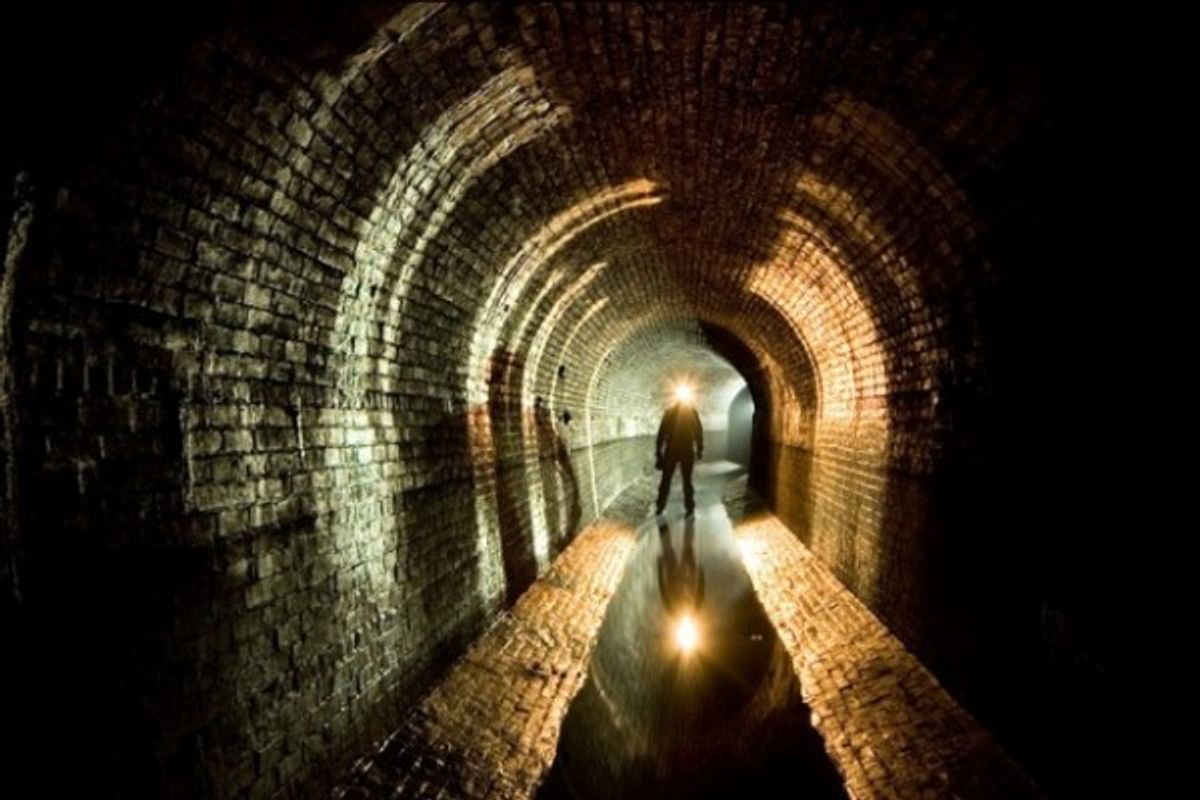

In the late 1990s, Duncan began exploring the abandoned subway tunnels and sewage systems beneath the city, as well as other forgotten piece of infrastructure. By 2005, he was regularly taking photographs of these dark, desolate places and has since had his work published everywhere from the New York Times to Wired to Gothamist. (Normally, you could find more of Duncan’s photography at his website Under City, which for the moment seems to be down.)

Below, we provide a brief interview with the photographer.

Next American City: How did you get started with underground photography?

Steve Duncan: When I came to New York in 1996 for college, it was my first time living in a big city. First I explored it as a tourist. For example, it seemed like an adventure to take the subway out to Brooklyn. I started reading about the history of how bridges and buildings were built. In addition, I heard rumors about fascinating places that were not on the tourist track. Some of these were a secret tunnel from Grand Central Station to the Waldorf-Astoria Hotel, or a sub-basement in an old building with an underground river trickling through it, or the abandoned subway stations and train tunnels.

Abandoned subway stations were some of the first underground places I entered. It was amazing to find these huge spaces, unused and lonely. In a city where every bit of space is filled with people, it was magical to find places where I could be as alone as if I were resting upon a mountaintop — when in reality, these places were no more than a few dozen feet below some of the busiest streets in the world.

I explored more of the city in 1998 by searching for the so-called ‘mole people.’ Nowadays there are not too many of them. There were many more people living in the tunnels of New York in the 1970s, ’80s and ’90s. But this fascinated me. If there were so many underground spaces in which people can live, I realized there is another world down there. Most people are not aware of this other world. There are historic places that teach us how cities were developed. So in 2001 I got my first camera to show the world what my eyes saw. It took me about four years to become a professional underground photographer.

NAC: What attracts you to these places?

Duncan: Visiting older tunnels brings out history first-hand. When I’m surrounded by the brick walls of a giant tunnel with only the light of my headlamp, it’s as if I were inside of a time capsule. It is amazing and beautiful.

NAC: Have you ever had any dangerous moments?

Duncan: I had a dangerous moment underground in New York in 2004. This happened when I started exploring sewers and drain tunnels. In Queens, some of the storm drains empty out into the Atlantic Ocean. The ends of the tunnels are below high tide. A friend and I went into one tunnel through a manhole. We entered during low tide. During high tide the tunnel fills up with water. We explored inland, but when we tried to exit a few hours later, we discovered the tunnel through which we’d entered was rapidly filling up.

This felt terrifying. We searched other side tunnels for manholes from which we could exit. The first two manholes we found were old and impossible to open. I was willing to hold onto the ladder underneath the stuck manhole for the next six hours. I prayed that the top of high tide would leave us breathing room, but my friend convinced me we should press on. Finally, wading with water at our necks and things floating by us, we found another manhole. We opened it. I later realized we probably would have drowned had we followed my plan.

Another scary moment came in Moscow. My fellow explorers and I followed an underground river tunnel that passes underneath Red Square. Due to a rain emergency, we exited out a manhole within sight of the Kremlin. We were glad we didn’t get arrested. Police never seem to appreciate history as much as me.

NAC: Do you have any upcoming plans for excursions?

Duncan: I conducted an above ground walking tour this past July through the Obscura Society called "Lost Streams of New York City." I’ll be returning to school in August. I might be sent to Las Vegas in early August to talk about drainage tunnels and the homeless who dwell there. We shot a documentary video there. It will premiere in New York in August.

Sharon Blumberg has been a writer and junior high school teacher for almost 20 years in Flossmoor, Ill. She lives in Munster, Ind. with her husband.

Shares