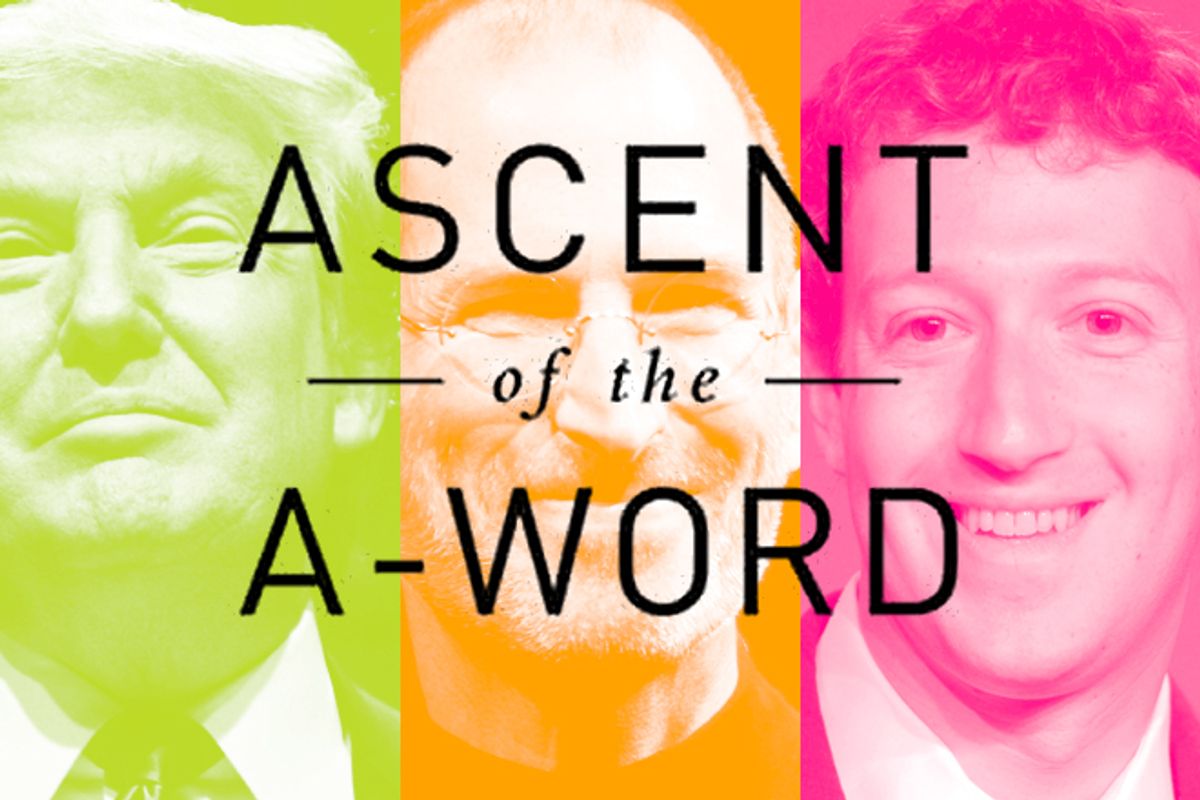

This is an age of assholism simply because we find the phenomenon and its practitioners so interesting — or provocative, or compelling, or compellingly repulsive, or sometimes all of those at once. I’m not thinking so much of assholes of opportunity like Charlie Sheen and Mel Gibson, or of incidental assholes like James Cameron or Brett Favre, whose assholism only adds a colorful sidebar to an independently impressive career. There’s little about those people that’s particular to the age, save that in earlier periods the public probably would have been spared the details of the personal tics and twitches that qualify them for the asshole label. What’s unique to our time is the fixation with certain iconic assholes, who exemplify each in his way the problematic allure of the species.

Steve Jobs, for example, was a modern personification of the asshole as achiever, someone whose assholism seems to be inextricable from his success as a leader. The traditional paragons of the type are the storied tough guys from military, business, and public life whose leadership styles are packaged in memoirs and advice books like "What It Takes to Be #1: Lombardi on Leadership," Rudy Giuliani’s "Leadership," "29 Leadership Secrets" from Jack Welch, and above all a four-foot shelf of inspirational works on George S. Patton, the first general to have been explicitly designated an asshole by both his men and his superiors. From "Patton on Leadership: Strategic Lessons for Corporate Warfare," we learn:

If he slapped a soldier, well, it was certainly wrong, but he thought it necessary for the morale of his troops. . . . It was often said that his troops would accomplish the impossible, then go out and do it all over again. “Patton’s men” may not have always truly appreciated the man’s leadership style at the time. Human nature is such that the discipline and the obedience required by a great leader are so often cause for griping and displeasure. But in retrospect, to have served under Patton was a red badge of courage to be worn forever.

The passage is calculated to reassure even the most abusive manager that he’s on the right track; it’s for the good of the team, after all, and whatever his subordinates may say about him, they’ll be grateful later on.

For some, Jobs fills an analogous role in the digital age. Shortly after his death and the publication of Walter Isaacson’s bestselling biography, Tom McNichol wrote in the Atlantic:

CEOs, middle managers and wannabe masters of the universe are currently devouring the Steve Jobs biography and thinking to themselves: “See! Steve Jobs was an asshole and he was one of the most successful businessmen on the planet. Maybe if I become an even bigger asshole I’ll be successful like Steve.”

And indeed, some observers depicted Jobs’ assholism as a deliberate management style. As Alan Deutschman put it in Newsweek, Jobs was a “master of psychological manipulation”:

He found that by delivering brutal putdowns of his co-workers he could test the strength of their conviction in their own ideas. . . . He found that many of the most brilliant engineers and creative types actually responded well to cruel criticism, since it reinforced their own secret belief that they weren’t living up to their vaunted potential.

Not everyone agrees with that assessment of Jobs’ skills as a manager; Isaacson says that he was terrible at it, and that success came despite his being a colossal asshole, not because of it. But it isn’t as if there are no advantages to being an asshole, in business or elsewhere. Life rarely makes moral choices that easy for us. When he was preparing "The No Asshole Rule: Building a Civilized Workplace and Surviving One That Isn’t," Robert Sutton reports he was repeatedly challenged by Silicon Valley leaders who asked him, “What about Steve Jobs?” to the point where he reluctantly added a chapter called “The Virtues of Assholes.” He concedes that judicious displays of irrational anger have their uses—fear of humiliation can be a motivator for employees if it’s balanced with the hope of praise, and a well-timed tantrum can get you a boarding pass at the last minute from uncooperative airport staff. And there are fields where behaving like an asshole offers a clear career advantage, such as professional wrestling and the law. Certain law firms encourage a hardball style that can cross over into what Sandra Day O’Connor has called legal Ramboism. As a former federal judge who became a partner at a notoriously aggressive Wall Street law firm said, “At Skadden Arps . . . we pride ourselves on being assholes. It’s part of the firm’s culture.”

Still, nobody would argue that being an asshole is essential to business success. The books on leadership that line the business sections of Barnes & Noble offer career models to suit every personality type. One can take one’s cues from successful leaders ranging from Bismarck and Golda Meir to Nelson Mandela and the apostle Paul, not to mention Generals Lee, Grant, Custer, and Attila the Hun. With that choice before them, the managers who make for the shelf that holds books on Patton and Jobs aren’t settling on assholism as a career expedient, they’re looking to justify their predilection for it. Few people become assholes reluctantly.

In any event, few of the people who bought Isaacson’s biography were looking for tips on becoming masters of the universe or pretexts for rationalizing their own arrogance. And the stories Isaacson tells about Jobs’ assholism are different from the ones that hagiographic biographers tell about Patton. They often demonstrate a capacity for irrationality, spitefulness, and petulance that had little to do with any psychological jujitsu: firing a manager in front of an auditorium of people; short-changing Steve Wozniak on a bonus in the early days of their partnership; taking credit for the ideas of others; screaming, crying, and threatening when the color of the vans ordered at NeXT didn’t match the shade of white of the manufacturing facility; and launching savagely into anyone who aroused his displeasure. (I know of one person who says he quit his high-level job at Apple because he got tired of wiping Jobs’ spittle off his glasses.) True, the Patton of historical fact was by most accounts even worse: a full-blown prick, sadist, and suck-up detested by both his superiors and his subordinates. But most of that has been left out of the story that made Patton an epitome of brilliant leadership, whereas Jobs’ pathological behavior is an essential element in his myth.

So it says something that Jobs’ assholism hasn’t been retouched for public consumption the way Patton’s was. That has a lot to do with the anti-heroic temper of the times; we demand all the dirt, especially on our heroes. But it also suggests a different idea of what makes these asshole achievers compelling, even to those with no interest in emulating them. Jobs’ tantrums and rants don’t evoke the resolute toughness of a Leader of Men so much as the temperament that we associate with creative genius. He styled himself as an artist rather than a businessman, the turtlenecked begetter of the cool exuded by the company’s iStuff. That was a credible posture in an age in which people found it natural to compare the launch of the iPhone to the previous generation’s Woodstock, and it seemed to license the prodigal shittiness that goes with being a Bernini, a Picasso or a Pound — or, for that matter, a Robert Plant. One reviewer of the Isaacson book compared reading it to “going backstage at a Led Zeppelin concert in the seventies and seeing your heroes wasted, and babbling like babies, surrounded by bimbos.” Indeed, Jobs was a rock star, in a sense that Bill Gates couldn’t possibly be, not just because he was idolized, but because he was one of those people like Jim Morrison, Kanye West and the Metallica guys, whose behavior as flaming assholes is taken as evidence of being exceptional enough to be able to get away with it.

• • •

Donald Trump comes closer than anyone else to being the archetype of the species; crossing genres, he exemplifies all the ways an asshole can capture our attention. He’s in a different league from Patton or Jobs, whose assholism is perceived relative to their other achievements — they’d be remembered even if they had been even-tempered and self-effacing, though perhaps not the subjects of a best-selling biography or an Oscar-winning biopic, whereas Trump would have no more claim on our attention than Harold Hamm, Charles Ergen, Dannine Avara or most of the other hundred-odd Americans who have more money than he does.

But Trump is a pure asshole in a way that very few people are ever a pure anything, as one dimensional as the villain in a Batman movie. Everything he says reveals the workings of a hermetically self-referential mind. Here he is explaining his objections to gay marriage:

It’s like in golf. A lot of people—I don’t want this to sound trivial—but a lot of people are switching to these really long putters, very unattractive. It’s weird. You see these great players with these really long putters, because they can’t sink three-footers anymore. And, I hate it. I am a traditionalist. I have so many fabulous friends who happen to be gay, but I am a traditionalist.

Not even Stephen Colbert could have come up with that; what ever else can be said about Trump, he writes his own stuff. And controversial as he is in other regards, no one disputes that he’s an asshole, though people have very different reasons for finding that compelling. Some regard him with de haut en bas disdain. In its heyday in the 1980s, Spy magazine made a fetish of his arriviste coarseness with the recurrent epithet “short-fingered vulgarian” (in retrospect, the “Not our class, dear” condescension of that phrase is a reminder of how tricky it is to deride an asshole from above). Others take pleasure in seething at his outrageousness. His presidential foray in early 2011, with its opportunistic rekindling of the birther dementia, briefly made him Topic A not just on the right but on the left—at the Huffington Post, mentions of Trump trail only those of Sarah Palin, who has been at the game much longer. At the time, even his online supporters conceded that he was an asshole, though they either looked past it or saw it as a plus. To some it meant that he was someone who would get the job done, à la Patton; to others that he wouldn’t mince words in letting the world know what an asshole Barack Obama is:

I will vote for him. The guy might be an asshole but the economy needs a fucking businessman at the helm.

I will vote for Trump, precisely because he is a jerk, but a jerk who knows when he’s getting screwed on a deal, and will make sure it is America that comes out on top.

Trump may be an arrogant asshole but he says what he thinks.

He says what so many ppl are thinking but is afraid to say it because of PC. trump is so fearless and does not give a dam about what ppl think about him. most ppl are afraid to speak their mind and say what they really believe because they will be called racist bigoted etc.

Trump’s preeminence in this line testifies to his mastery of the mechanisms of publicity. Apart from Colbert, no one in public life understands better than he how engaging assholism can be, both in real life and in its broadcast simulacra. "The Apprentice" epitomizes the genre of reality television built around situations in which people can be abusive to others who have willingly consented to take part in return for money or celebrity. Every episode arcs towards a finale that gives the viewers the opportunity to watch a powerful man acting like an asshole towards his supplicants, dispatching the losing competitor with a brisk, “You’re fired.” The phrase is supposed to evoke the pitilessness it takes to survive in “the ultimate jungle,” but we don’t actually feel much compassion for the losers. They’ve fought to get there, after all, and any residual sympathy we might have had for them is dissipated in the final boardroom scene where they’re incited to act like assholes themselves, selling each other out in an effort to be spared the axe. And anyway, “fired” here really means “playing a subordinate role in the rest of this season’s episodes.” So there’s none of the vicarious outrage we might feel watching a movie of the week that depicts Leona Helmsley summarily discharging a busboy who spilled some tea in her saucer.

Those scenarios are reproduced, with variations, across many of the genres of reality television, from "American Idol" to "What Not to Wear" to Gordon Ramsay’s "Restaurant Makeover" (which offers, Gina Bellafante said in the New York Times, “the thrill of . . . witnessing someone so at peace with his own arrogance”). In each instance, the format keeps the “reality” close enough to the actual so that the asshole’s behavior is distressing to his targets without ever reaching so deep into their lives that it becomes genuinely disturbing to the viewer. They allow us to enjoy the spectacle of social aggression without experiencing any vicarious moral risk, in the same way that “dare” shows like "Fear Factor" allow us to watch contestants attempt to jump from one building to another without any real physical danger. On the contrary, our indignation over the behavior of the designated assholes on the job-search shows like "The Apprentice" and the documentary-style shows like those in the Real Housewives franchise isn’t diminished by knowing how much of it is engineered by the producers or simulated for the camera. It’s the same suspension of disbelief that makes possible the Comedy Central roasts, in which some celebrity, ideally a high-profile asshole himself, winces good-humoredly as comedians who have never met him take turns making pointed put-downs at his expense. (“When Trump bangs a supermodel, he closes his eyes and imagines he’s jerking off.”) There have been eras that took a far more intense interest in spectacles of cruelty than ours, but none that was so transfixed by watching people act like assholes.

That fascination is fed in equal parts by our fantasies of rock star self-indulgence and the resentments and anxieties that assholes evoke. Both are popular themes in recent cinema. I’m not thinking so much of the innumerable comedies and dramas that feature assholes as their stock villains, but of movies in which the assholes are the focus of dramatic interest. Some of these are tales of asshole redemption, like "Rain Man" and all those other Tom Cruise vehicles. Others are more equivocal about the condition, like "The Company of Men," "The Politician," "Greenberg," "Margin Call" and "Rules of Attraction," as well as the mean-girl movies like "Heathers" and "Mean Girls" itself, which break new generic ground. Meanwhile, television has made a mini-industry of the dirtbag sitcoms that I mentioned earlier. And one should make a special place for "The Office," especially the original version with Ricky Gervais, which created one of the most incisive modern portraits of the asshole’s clueless self-delusion. Gervais’ David Brent elicits contempt and irritation, pity, even affection — a sign not so much of the complexity of the character but of how conflicted we are about the type he personifies.

• • •

Some of these assholes are just old curs warmed over, but others are creatures new to film. "The Social Network," for example, could have been subtitled "Asshole 2.0." There are obvious resemblances between Mark Zuckerberg and Steve Jobs as driven high-tech creators, but the character of Zuckerberg created by Aaron Sorkin and David Fincher (which by all accounts is substantially different from the real Zuckerberg) belongs to a different genus of assholes. No one would be tempted to describe him as a “master of psychological manipulation,” as Newsweek did Jobs; he’s arrogant, self-absorbed, and insensitive to the point of near-autism. In the opening scene, he preens and condescends to his girlfriend, Erica, in a Cambridge bar (“You don’t have to study . . . You go to BU [Boston University]”). She tells him he’s an asshole, breaks up with him, and walks out. As if to prove her right, he goes back to his dorm and posts some unflattering and sexist remarks about her on his blog, then, in a misogynistic follow-up, creates the “Facemash” application that allows people to rank the women students for hotness. Later we see him cutting out his best friend, who put up the money for the project, and responding with prodigal snottiness to a lawyer who’s deposing him:

GAGE: You don’t think I deserve your attention. . . .

ZUCKERBERG: You have part of my attention. You have the minimum amount. The rest of my attention is back at the offices of Facebook, where my colleagues and I are doing things that no one in this room, including and especially your clients, are intellectually or creatively capable of doing.

Only in an incongruously mawkish final scene does Zuckerberg reveal a dim awareness of his isolation and loneliness, as he sits alone at a conference table in the offices of his lawyers and sends a Facebook friend request to his former girlfriend, Erica, then keeps compulsively refreshing the page to see if there’s a response. All of a sudden he’s pathetic, and for the first time strikes us as a possible object of sympathy. “You’re not really an asshole,” his lawyer, Julie, has told him, but what the scene really shows is that he’s only an asshole, not an unmitigated shit like most of the other characters — the slick hustler Sean Parker, the supercilious and self-infatuated Winklevoss twins who accused him of stealing their idea.

That last scene put several critics in mind of Charles Foster Kane’s “Rosebud,” and it seems to set the movie in the long line of American stories that show successful figures repaid for their unchecked ambition with loneliness. The scene is obviously meant to leave the audience with the consoling thought that it profiteth a man nothing if he gains the world but loses his soul mate. But there are no real film antecedents for the figure of the emotionally stunted nerd billionaire (a very far cry from Mickey Rooney in "Young Tom Edison"), just as there are no media precursors of the digital culture that seems to many to foster a kindred sense of disconnection and casual meanness. Or at least that’s the perception of many people in the generation of Sorkin and Fincher, who were in their late forties when the film was made. They obviously meant for their Zuckerberg to personify the digital culture, as they signaled in the ambiguous title "The Social Network." That’s how Zadie Smith read the story in the New York Review of Books:

Shouldn’t we struggle against Facebook? Everything in it is reduced to the size of its founder . . . Poking, because that’s what shy boys do to girls they are scared to talk to. Preoccupied with personal trivia, because Mark Zuckerberg thinks the exchange of personal trivia is what “friendship” is . . . We were going to live online. It was going to be extraordinary. Yet what kind of living is this? Step back from your Facebook Wall for a moment: Doesn’t it, suddenly, look a little ridiculous? Your life in this format?

But that’s not how people who grew up with Facebook see either Zuckerberg or his creation. When I talk to Berkeley undergraduates about the movie (which they’ve apparently all seen), they acknowledge that Zuckerberg behaved badly, but they don’t see him as the alien and alienating figure that Sorkin and Fincher made him out to be — he’s a routine sort of jerk, and if they have it in for him, it’s more often because of Facebook’s privacy policies than any of the wrongs committed by his movie avatar. Nor would they recognize either Facebook or themselves in Smith’s description of the online world. They don’t see their walls and profiles as the places where they live their lives, just as one of the many venues, material and immaterial, where they circulate. And they’re quite clear on the difference between friends and “friends.” As one student of mine wrote, after describing the assortment of postings on his Facebok wall from classmates, acquaintances, and already forgotten high-school chums, “If I thought this was a representation of my actual life, I’d need to reevaluate it pronto.”

In the same way, digital natives aren’t as disturbed as their parents are by the snark and assholism endemic in the online world, not because the perpetrators aren’t assholes, but because they’re relatively harmless ones. It’s a curious feature of the age that the forms of assholism that people find most alarming tend to be those that have less drastic effects on their daily lives. Abusive blog comments are easier to ignore or shrug off than rude remarks from people behind you in the line at the DMV. But for just that reason, the more remote and impersonal forms of assholism are easier to engage in without rippling one’s conscience too much. And while these activities don’t generally inflict the personal injuries that assholism can at work or school, they can be enormously destructive of the fabric of public life.

From the book "Ascent of the A-Word" by Geoffrey Nunberg. Reprinted by arrangement with PublicAffairs, a member of the Perseus Books Group. Copyright © 2012.

Shares