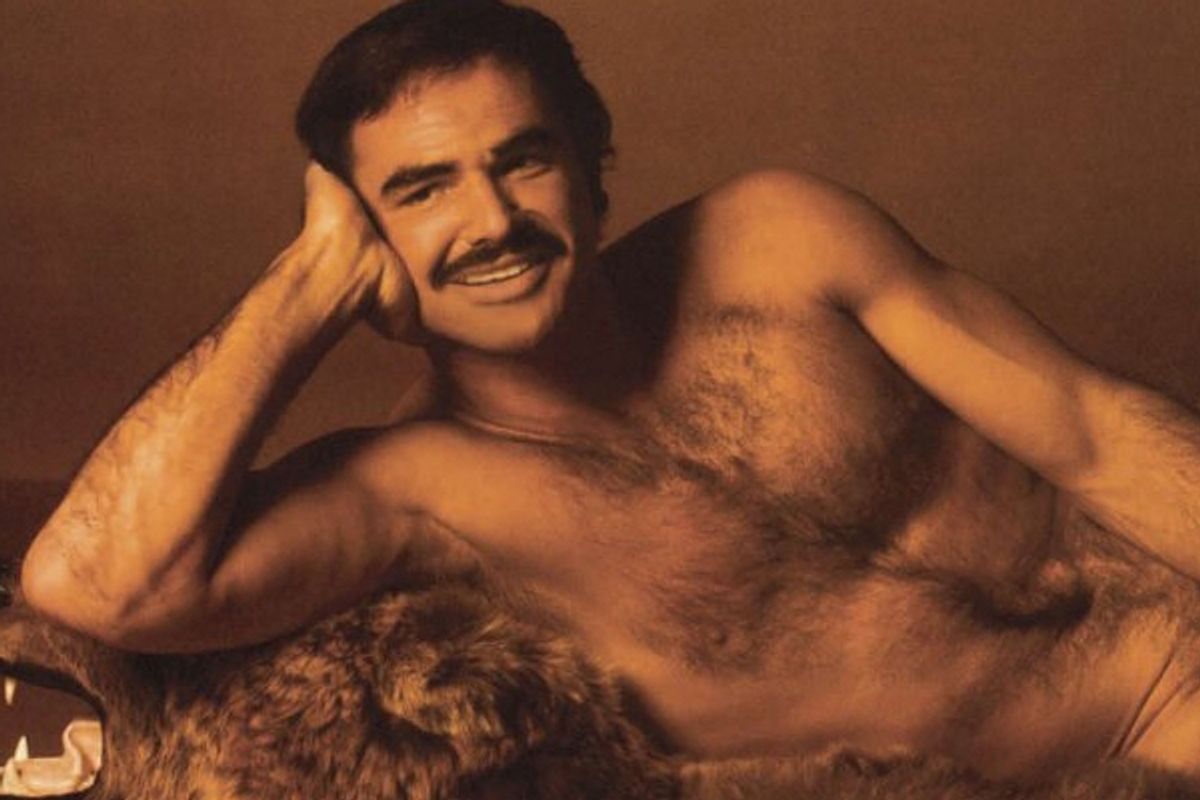

I gasped when I saw it: Burt Reynolds, all careless lean muscle, his chest only slightly less thickly grown than the bear rug on which he languidly stretched. All this, among the highly waxed and toned female flesh of the 2007 Sports Illustrated swimsuit edition. The Cosmopolitan centerfold commissioned by Helen Gurley Brown in 1972 had been reborn as a gatefold ad for DirecTV (sans cigarette). When I half-jokingly tacked it up, first on my cubicle wall and then on my apartment fridge, reactions were somewhere between horror and sexual fascination, or a mix of both.

"I thought one day when I was washing dishes that men like to look at our bodies, and we like to look at their bodies, though it's not as well known," Helen Gurley Brown told me by phone that year, when she was 86, for a story I wrote on the ad campaign in Women's Wear Daily. What Helen Gurley Brown did for the female body is well known. She exhorted it as a liberated, occasionally transactional asset; tarted it up for the cover of Cosmo; and even declared its essential autonomy. Somehow, her desire to objectify male bodies never got as far.

She did manage to get Burt Reynolds' enthusiastic participation in her first-ever nude male centerfold. "There's a big show in this country called 'The Tonight Show,'" she explained to me. "He was a guest host, and I asked him off the air." The photo that ran was Reynolds' personal pick. "He's got a good body, he's got terrific legs, he's handsome, he's smiling up a storm and you can't really see any" — here, she paused — "men's genitalia … It's about as sexy and revealing as a photo can be, but it doesn't reveal anything that it shouldn't."

The photo, which ran with text proclaiming that male editors had previously "neglected the visual appetites of us equally appreciative girls," was a sensation. Women mobbed Reynolds' house. The founder of Playgirl even cited it as an inspiration for the entire creation of the magazine: "When I saw Burt Reynolds naked in Cosmo and saw what a winner that was, it came to me, that's what women want. If a woman says to me she wants to see a man's smile, his eyes, I say, 'Don't lie to me -- you want to see a man's dong,' that is if you're normal."

In "Bad Girls Go Everywhere," Gurley Brown's biographer, Jennifer Scanlon represents Gurley Brown as a feminist whose attitudes towards sex prefigured "sex positive" feminism. That included acknowledging female desire, particularly a desire for men's bodies. Gurley's stubborn refusal to "demonize" men, or have any unpleasantness at all in her magazine, kept her at loggerheads with many second wavers; she saw it as simply practical. “I acknowledge that men keep women back,” Gurley Brown wrote, “but since sex is terrific and it comes from men, you can’t rule men out of this world and say they’re all terrible and rotten, because you’re going to need them for your own purposes.”

Scanlon notes, “Although she does not use the word ‘desire,’ the truth is that, for Brown, sex is desire, and desire is altogether natural and healthy. ‘You inherited your proclivity for it,’ she writes about women’s interest in sex. ‘It isn’t some random piece of mischief you dreamed up because you’re a bad, wicked girl.'” In her review of Scanlon's book, Judith Thurman pointed out that Gurley had written in "Sex and the Single Girl" that “liking men is ... by and large just about the sexiest thing you can do. But I mean really liking, not just pretending. And there is quite a lot more to it than simply wagging your tail."

The male centerfolds didn't last long. Still, Gurley Brown told me, "We kind of started something. Though I still don't see that many pictures of naked men in women's magazines." If only she'd had the chance to get to know the Internet.

Shares