In the hours immediately after George McGovern picked Sen. Thomas Eagleton to be his 1972 running mate, Marc Howard, a television reporter for the local New York City station WPIX, heard murmurs in Miami Beach that Eagleton had a history of alcohol abuse. Throughout the spring, Howard had developed a cordial relationship with McGovern political director Frank Mankiewicz, calling him every few weeks or so for updates on the campaign and verification of various stories. So he gave him a ring to check out the report, and Mankiewicz persuaded him not to broadcast this story that evening. Robert Sam Anson, the McGovern biographer, also heard from a source that Eagleton “has some problems.” The source told Anson that Eagleton drank a lot. “And I think he’s been in the loony bin,” he said. Anson knew that several similar allegations were zipping through the corridors of Miami Beach’s waterfront hotels, so he reasoned that the general thrust must have some grounding in the truth, even if the specifics were wrong. By 8 p.m. he reached the seventeenth floor of the Doral, where he grabbed McGovern press secretary Dick Dougherty and McGovern administrative assistant Gordon Weil, anxious to pass along what he had learned.

“What you’ve got is just some bullshit put out by the Republican National Committee,” Weil told Anson.

“Well, when that bullshit hits the fan, don’t say I didn’t warn you,” the reporter shot back.

“It’s too late now, anyway,” Weil said.

The convention’s frustration at the last-minute, closed-door nature of the vice presidential selection process stalled its ratification of McGovern’s vice presidential pick. McGovern’s decision process was typical of the way past presidential nominees had chosen their nominations for running mate, and some delegates hoped to repudiate the perceptibly antiquated process rather than his pick itself. Did the 1972 convention represent an “open convention,” a “new day” in Democratic politics? Or was McGovern’s running-mate selection process an expression of Old Politics as usual? As a series of overlooked vice presidential hopefuls such as Mike Gravel and Endicott Peabody took the convention’s stage to promote their candidacies, they snatched the prime-time television audience McGovern had counted on addressing and surrendered the Democratic Party’s best venue for articulating its vision to the nation at large.

Tom Ottenad of the St. Louis Post-Dispatch gained access to Eagleton in a makeshift plywood waiting room behind the podium. Chain-smoking while nursing an orange juice, Eagleton gave his hometown newspaper’s star political reporter his assessment of the campaign ahead while keeping an eye on the television broadcasting the action from the convention floor. “I don’t know the exact timing,” Eagleton said, “but I got the impression we’re not going to vegetate between now and Labor Day, which has been the traditional starting day,” relating the plans for the campaign he gleaned from McGovern and his staff that afternoon. Just yards away, at the Convention Hall podium, Mayor Kenneth A. Gibson of Newark, N.J., one of the nation’s most prominent black politicians, put forth Eagleton’s name for the vice presidency. As a black man, Gibson was a symbolic pick to be Eagleton’s nominator, displacing Missouri governor Warren Hearnes in the role at the McGovern campaign’s insistence. Gibson described the Missouri senator as a man “committed to the belief that our first national priority and obligation is to one another, be we rich or poor, young or old, black, brown, or white.” New Mexico lieutenant governor Roberto Mondragón seconded the nomination of Eagleton, beginning his remarks in Spanish, probably a first in Democratic Party history and another gesture toward inclusion. He was followed by another seconding speech from Debbie Barber, a twenty-year-old speech therapy student at the University of Missouri, Columbia, and a representative of both the youth and the women on the Missouri delegation. Eagleton picked up some of her remarks and noted to Ottenad with a measure of pride in his voice, “I’m the youngest one nominated for vice president in 120 years.” However, Barber had her facts wrong. Franklin Delano Roosevelt was thirty-eight to Eagleton’s forty-two when James Cox named FDR to his ticket in 1920. Others had also been younger.

Eagleton’s concentration returned to the interview, and he answered Ottenad’s request for him to define the central issue of the campaign. “Change,” he said. “Can we, the Democratic Party, do what Nixon promised to [do] but never fulfilled—bring this country together?” It seemed that McGovern had called upon him to do just that, but on a smaller scale first—bring the Democratic Party together. Eagleton told Ottenad that McGovern had suggested he would have “special responsibilities in the big cities,” and be charged with reaching out to the Democratic establishment. Within minutes Eagleton received a call from Ed Muskie, the man who had held Eagleton’s role four years earlier and had used the appointment to launch his own presidential ambitions. He had also been Eagleton’s first choice for president that year. “Ed,” Eagleton said, “if I can end up being half as good a vice presidential candidate as you were, I’d consider myself a success. I hope you’ll give us your help this fall.” Eagleton was already attacking the task at hand, winning over the party regulars. Hubert Humphrey soon stopped by the waiting room. “Have you got a little acceptance speech?” the one-time vice president and three-time presidential hopeful inquired of Eagleton. Later, as Humphrey was leaving, Eagleton entreated, “You know, I’m going to need some guidance.”

“You’re going to get it,” Humphrey assured him. “Go get ’em.”

Meanwhile, Mike Gravel had taken the podium to deliver his own seconding speech to his self-endorsed nomination for the vice presidency. It seemed to be another convention first in a year in which the fictional television character Archie Bunker of "All in the Family"; labor activist César Chávez; Chinese dictator Mao Zedong; U.S. Attorney General John Mitchell’s wife, Martha; CBS reporter Roger Mudd; consumer advocate Ralph Nader; and famous pediatrician and People’s Party candidate Dr. Benjamin Spock were all among the names submitted for consideration during the vice presidential roll call. Newsweek called the evening “a comic interlude, a burst of silliness on the part of the delegates whose taut bonds of decorum and discipline seemed suddenly to snap, now that it didn’t make a difference.” But the litany of nominating and seconding speeches had real implications. McGovern’s acceptance speech was pushed late into the night, depriving the candidate of the prime-time audience he needed.

The commotion over Gravel’s seconding speech caught Eagleton’s attention, and he called over his thirty-year-old press secretary, Mike Kelley, who had flown to Miami that evening. Kelley was of middling height, and had dirty-blond hair and an Irish complexion. The son of a newspaper reporter, Kelley had started working as a copyboy for the Kansas City Star while still in college, eventually becoming a reporter. He was a straight shooter and had a wry sense of humor. “Hey, what’s Mike Gravel doing? Is he hanging me?” Eagleton asked him. Kelley filled him in, then Eagleton resumed recounting his late-afternoon discussion with McGovern for Ottenad, the Post-Dispatch reporter. “We agreed that a vital ingredient to success is a massive, intensive voter registration drive, directed to the young and the blacks in the major cities,” Eagleton recounted. Eagleton clearly brimmed with excitement for the vice presidency and appeared to have forgotten the joke about two brothers he had shared in 1965, while lieutenant governor of Missouri, the state-level approximation of vice president: “One of [the brothers] went to sea, and the other became the vice president. And neither of them has been heard of since.”

Eagleton’s nomination also thrilled the Missouri delegation, and its distress over McGovern’s candidacy appeared to have evaporated. Though the delegation had withheld the majority of its votes from McGovern on key planks earlier that week, it now threw its unanimous support behind the McGovern-Eagleton ticket. Governor Hearnes, who had previously resisted McGovern and resented Eagleton for abandoning Muskie on the California Challenge, now took pride in his fellow Missourian and felt gratified by his state’s newfound influence—even if he was disappointed that the McGovernites had deprived him of his seconding speech. “History has a way of repeating itself,” Hearnes proclaimed as he cast the state’s votes, recalling Missourian Harry Truman’s service as vice president before becoming commander in chief. Even Alabama, the dominion of Governor George Wallace, principal antagonist of the party’s liberals, seemed to play along with the idea of Democratic unity. “If Governor Wallace was casting these thirty-seven votes, he would want them all to go to Senator Eagleton,” the Alabama state Democratic chairman announced just before 1 a.m. However, on this last night of the convention, some McGovernites had assumed the role of spoiler, delaying the roll call with the litany of pet nominations and seconding speeches, and voting for—among others—Frances “Sissy” Farenthold of the Texas House of Representatives, a move intended as retribution for the McGovern campaign’s betrayal of the women on the South Carolina Challenge.

Finally, about an hour and twenty minutes into the roll call, at around 1:50 a.m., after the Texas delegation cast its votes, Democratic National Committee chairman Larry O’Brien introduced a motion to halt the voting and hand the nomination to Eagleton by acclamation, a symbolic gesture in the direction of party unity. For the first time all week, the Missouri delegation unfurled its state banner and waved it in celebration, finally content with the party. The arena erupted in a resounding—if delayed—ovation of song, dance, and apparent reconciliation among the Democratic Party’s various factions.

In the VIP box where Barbara Eagleton watched with her two children, who had arrived in Miami that evening, the running mate’s son Terence tossed a handful of confetti overhead. Reporters and cameramen had been keeping them company all night, and Barbara seemed entirely equal to the role of vice presidential wife. Though immaculate in presentation, she predicted, “I don’t think it will be a ‘What are you wearing?’ and ‘How are you doing your hair?’ kind of campaign.”

As Eagleton waited backstage, eager to live the moment when “Tom Who?” became “Tom Eagleton,” he reflected on his life up to that point. “Eagleton, you are a mighty lucky kid,” he thought. “You lucked into circuit attorney of St. Louis. You got some good breaks and became attorney general of Missouri. By happenstance and fate you became U.S. senator from Missouri. Now you are being nominated for the second-highest office in the free world.” Eagleton knew he had enjoyed a charmed rise to his spot on a national ticket. “God has been good to you,” Eagleton acknowledged. “I hope God gives you the strength and courage to do the job for which you are being nominated.”

Governor Hearnes, Senator Stuart Symington, and representatives Leonor K. Sullivan and William Clay of St. Louis congressional districts—all Missourians and each an influence on Senator Eagleton’s political career, Old Politics and New Politics alike—accompanied the vice presidential candidate to the podium for his speech. His face dripping with sweat and his hands quivering in a combination of excitement and nervousness, Eagleton accepted his party’s vice presidential nomination. “From the people who promised to bring us together, we have gotten deception and more mistrust,” he said, pointing to the failings of the Nixon administration. “From the people who promised the lift of a driving dream, we have a sodden mound of shattered hopes. We have an electorate so jaded by gimmickry that their healthy skepticism about politics and politicians has escalated into a total lack of confidence in the administration,” he said. Eagleton promised to restore “dignity to the second highest office in the United States” and to steer clear of the “cheap rhetorical attacks that divide our nation,” a not so subtle jab at Vice President Spiro T. Agnew, known for his fear mongering and divisiveness. Looking ahead, Eagleton implored the convention before him, “Let us conduct ourselves and our campaign and, indeed, our lives, so that in later years men may say 1972 was the year, not when America lost its way, but the year when America found its conscience.” He told the convention that, for him, the nomination capped a year rife with political surprises. Just as few people had suspected that Mc-Govern would rise to the nomination, his own ascent was, as he had described it, “a distinct improbability.” As applause interrupted his delivery, Eagleton smiled broadly. He said he dedicated his address to M.D.E., leaving those who knew him to realize that he meant his father.

Ted Kennedy had flown down to Miami to partake in the show of unity, reveling in the crowd’s affection for him, “the best living tradition in this party today,” as one delegate phrased it. Banners bearing portraits of his two deceased brothers hung above the convention floor. “Democrats are united by heritage, by conviction, and unyielding opposition to Republican leadership,” Kennedy affirmed, attempting to connect the McGovern campaign to the party of years past and fitting the South Dakotan squarely in the Democratic tradition. “In 1948, Hubert H. Humphrey proclaimed a dedication to the equality of all races, and Harry Truman took this to the people. And George McGovern would do the same. Lyndon Johnson promised we shall overcome. And, beginning next January, under the leadership of George McGovern, we shall overcome.” The crowd concurred, rising in ovation, another fleeting moment of unity in a year characterized not only by surprises but also by division.

When he arrived at the podium at 2:48 a.m., McGovern began with self-deprecating humor. “I assume that everyone here is impressed with my control of this convention in that my choice for vice president was challenged by only thirty-nine other nominees. But I think we learned from watching the Republicans four years ago as they selected their vice presidential nominee that it pays to take a little more time,” he said—a sure applause line, as Democrats of all stripes reviled Agnew.

According to the Nielsen ratings, an average of 17.8 million homes—or approximately 71 million Americans—watched the convention during prime time that week. On Thursday evening, the night of McGovern’s address, 17.4 million homes tuned in during prime time, but only 3.6 million televisions remained on by the time McGovern spoke. Despite the chaos of Chicago, even Humphrey had gotten to address the nation in prime time in 1968.

McGovern’s speech resembled a sermon, showcasing the preacher’s son’s propensity for outlining America’s choices in moral terms and for drawing from the Bible to affirm the rightness of his cause. “In Scripture and in the music of our children we are told: to everything there is a season, and a time to every purpose under heaven. . . . This is a time for truth, not falsehood,” he proclaimed. “Truth is a habit of integrity, not a strategy of politics. And if we nurture the habit of candor in this campaign, we will continue to be candid once we are in the White House.” Who could have foretold that doubts about Eagleton’s candor and McGovern’s own were soon to become his campaign’s greatest liability? “From secrecy and deception in high places, come home, America,” McGovern said, launching his speech’s most memorable refrain. And, in a conclusion that amplified his trademark moralism, McGovern prayed, “May God grant us the wisdom to cherish this good land and to meet the challenge that beckons us home.” In addition to the task of bringing America home from its war in Indochina, from its excessive military spending, from its unjust tax laws, from its prejudices, and from all other ills that plagued the nation, it seemed that McGovern would require godlike wisdom to overcome the unique challenges of his own campaign.

As McGovern spoke, Eagleton administrative assistant Doug Bennet watched the broadcast from the ersatz plywood waiting room, preparing himself for the task at hand by drawing upon the lessons of his past campaigns, Muskie’s included. “First, having been in some poorly organized campaigns, I meant to make this one really work well,” Bennet recalled of his thoughts. “And, second, I would make every effort to avoid the kind of clash between the presidential and vice-presidential staffs which seems to have developed in the past.”

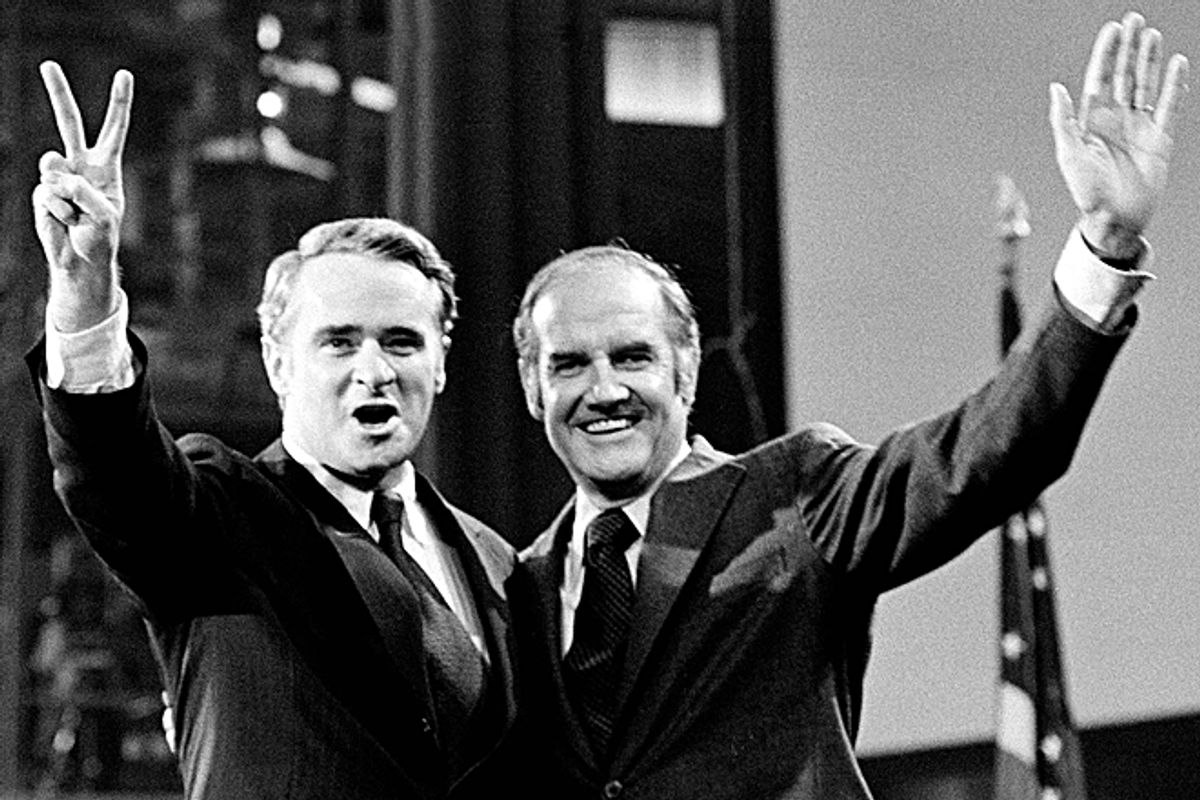

Back in the Convention Hall, standing at the center of the podium, McGovern and Eagleton clasped their hands and raised them above their heads like Olympic gold medalists, inspiring the crowd to roar in celebration of their union. Eagleton was glowing.

Before the exhausting convention adjourned at 3:26 a.m., Kennedy, Humphrey, Muskie, New York Congresswoman Shirley Chisholm, and Scoop Jackson all joined McGovern and Eagleton onstage. The party leaders—once rivals, now apparently compatriots—linked arms in unity and bowed for the convention audience as the band played, “Hail, Hail, the Gang’s All Here.” Democrats of all stripes—black, white, northern, southern, urban, suburban, young, old, blue-collar, white-collar—joined in singing “Happy Days Are Here Again.”

- - - - - - - - - - - - - -

With a dizzying week of official convention proceedings complete at long last, the McGovern and Eagleton teams returned to the Doral Hotel to meet, greet, and continue the party. Doug Bennet and Gordon Weil landed in the same elevator up. When the door opened on the seventeenth floor, Weil urged Bennet to follow him to his room first, before joining the festivities on the Starlight Roof. He told Bennet that the campaign had selected Eagleton despite rumors that he had been hospitalized for alcoholism. As Bennet remembered it, Weil did not ask whether the allegations were true, which he took to mean that, even if they were, the campaign felt that they would not hurt the ticket. Weil recalled telling Bennet that it would be best for the campaign to know everything relating to the rumors so that it could prepare the appropriate response should the information surface in the press. Bennet clarified the situation, telling Weil that, yes, the vice presidential nominee had been hospitalized—but for “fatigue and depression,” not a drinking problem. “Oh, well that’s a relief,” Weil said. “We knew we were right. He hadn’t had a drinking problem.” Bennet withheld details of Eagleton’s treatment, other than to state the general cause. While he knew his boss had been hospitalized and treated with shock therapy, nothing about his behavior during the three years Bennet had been working for the senator suggested that depression continued to plague Eagleton. “I’d never seen any evidence of a disability of any kind,” Bennet explained four years later. Eagleton had “conquered it. It was in his past. . . . Nothing triggered in my mind the possibility that this was a problem.” With such benefit of distance and time for reflection, Bennet added, “Now, obviously, that’s one of the colossal failures of political judgment, I guess, of all time.”

Before 4 a.m., the two men joined the party down the hall, and Weil updated Mankiewicz on his conversation with Bennet. As Eagleton prepared to leave the Starlight Roof, Mankiewicz caught him at the door. “We ought to talk about that health problem,” Mankiewicz said.

Perhaps fatigue, or the seeming impossibility of Eagleton’s selection, explains why Mankiewicz forgot to mention in the staff meetings that morning that he knew Eagleton had been hospitalized twice for “nervous breakdowns.” Back in June, about a week before the Missouri state Democratic convention, Scott Lilly, the former Eagleton staffer and current McGovern aide, had proposed to Mankiewicz the idea of spreading a rumor that McGovern was considering naming Eagleton his running mate. Given Eagleton’s popularity in his home state, Lilly believed this ploy would entice more Missourians to embrace McGovern and thus facilitate greater representation of McGovernites on the state’s delegation to Miami Beach. In seeking the campaign’s permission to enact this scheme, Lilly volunteered to Mankiewicz that, contrary to the rumors, Eagleton did not have a drinking problem. However, Lilly said only that Eagleton had received psychiatric care during two hospitalizations—after victorious but trying election campaigns in 1960 and 1966. Mankiewicz approved Lilly’s plan. Lilly had not known about Eagleton’s 1964 hospitalization or his treatment with electroshock, and thus neither did Mankiewicz.

Yet Mankiewicz also later recalled that, a few weeks before the convention, a friend and fellow board member of his sons’ private school had warned him not to let the campaign nominate Eagleton. “I just saw [Eagleton] at a press conference,” the man, a respected Washington psychiatrist, told him. “And he has a pronounced tremor in his hands. And the way he kept answering questions suggested to me he’s got trouble,” the psychiatrist continued. “Oh, shit,” Mankiewicz recalled thinking at the time. In the exhaustion and bustle of the convention, both omens slipped from Mankiewicz’s mind the day the campaign went about selecting its number two.

When a prominent Democrat read in the papers that morning of increasing speculation that McGovern would pick Eagleton, he called the candidate’s staff, hoping his knowledge that Eagleton had been twice hospitalized for psychiatric care would preempt the selection of the Missourian. After several attempts to contact someone in the McGovern organization, the man finally reached Anne Wexler, an old friend and aide high in the campaign. Wexler confirmed receiving the report and said she passed it along to key McGovern strategist Rick Stearns, who denied ever getting it, saying that he was napping when Wexler supposedly told him. In the end, the message never reached McGovern.

When the Democratic informant heard that McGovern had chosen Eagleton, he called the campaign back: “What in the name of God are you smoking up there?” he asked.

Excerpted from "The 18-Day Running Mate: McGovern, Eagleton and a Campaign in Crisis" by Joshua Glasser (Yale University Press). Copyright 2012. Reprinted with permission of the author and publisher.

Shares