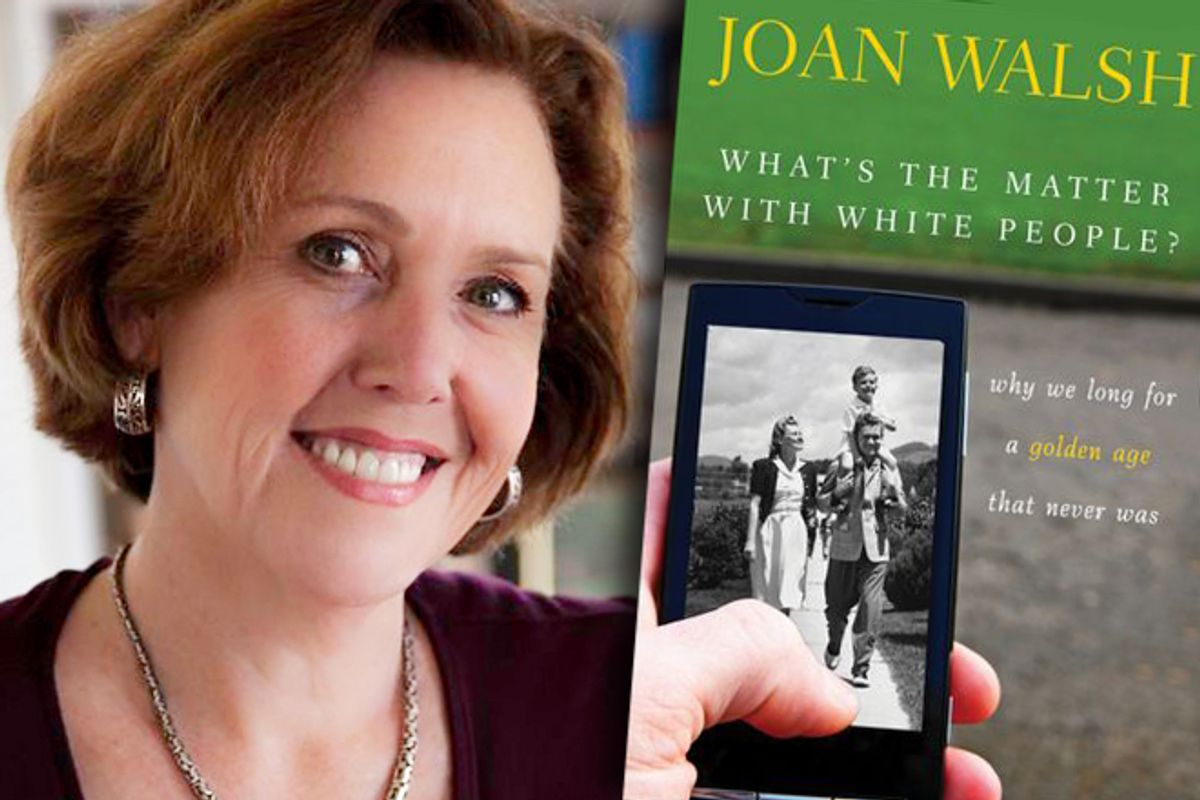

Joan Walsh’s family, as she writes in her new book “What’s the Matter With White People? Why We Long for a Golden Age That Never Was,” participated in two of the great migrations of 20th-century American history. Joan was born in Brooklyn, N.Y., but mostly grew up in suburbia (first on Long Island and later in Wisconsin). As that happened she watched many of her Irish-American family members morph from bedrock New Deal-JFK Democrats into Nixon-Reagan Republicans. In her book, Joan tries to wrestle with this legacy as honestly and forthrightly as she can, without betraying either her family’s complicated lived experience or her own passionate commitment to social, racial and economic justice.

“What’s the Matter With White People?” is sure to provoke much discussion during the fall campaign, with its personal and historical approach to one of the most toxic issues in American politics: How and why the white working class became the Republican base, in defiance of its own economic interests, and whether the Democrats can ever win it back. Along the way it’s also a family memoir that captures a specific period in the history of Irish-American assimilation, one that resonated strongly with me (and will also with you, if you have immigrant roots), and an account of Joan’s somewhat improbable rise to fame as an MSNBC commentator, which came about in large part because she embraced her working-class, Irish Catholic roots. Joan revisits many of the questions of the bitter 2008 Democratic campaign between Barack Obama and Hillary Clinton – which thrust issues of race and class back into the national consciousness – and argues that Obama now has the opportunity to embrace a broad, inclusive economic agenda that can both win this year’s election and help to heal the nation’s worsening caste divide.

But this isn’t a book review, for obvious reasons. Across a dozen years or so as Salon colleagues, Joan has been my co-worker, my boss and then a co-worker again (as well as a TV personality). We have had a number of late-night political debates, mostly friendly and occasionally argumentative. (One of those was about the fate of Hubert Humphrey in the 1968 presidential election, which took place when we were barely schoolchildren.) To stereotype both of us ruthlessly, Joan’s passion is the muddy trenches of politics, full of blood and compromise, while I’ve spent most of my journalistic career watching from the ivory tower of culture, with the other pointy-headed intellectuals. I am profoundly grateful to her for not mentioning, amid all the rough-and-tumble in her book, that I wrote a fervent Salon article defending my vote for Ralph Nader in the 2000 election. (Want someone to blame for eight years of Bush? Mea culpa.)

Over the years we’ve picked up that we have strikingly similar Irish-American family histories, and strikingly dissimilar approaches to framing the major issues of the day. Joan’s father and my father were both the children of recent immigrants, and were born two years apart in adjoining New York neighborhoods. Both were the first kids in their extended families to go to college and break through to the middle class, and both remained liberal Democrats as many of their relatives drifted into the Reagan coalition. While Joan was born in Brooklyn and has lived in the San Francisco Bay Area for many years, I was born in the Bay Area and now live in Brooklyn. That’s where we met for lunch, in a lovely, tree-lined, multiracial neighborhood that looks like a 3-D Obama commercial, to talk about what in fact is wrong with white people.

So is there anything in this book that you’re anxious about your family reading?

Of course. Any time I've written anything about my family, people get upset about focusing on the negativity. I say in the book that I once called the Christian Brothers [monastic order] "foster care for the Irish poor," and that remains a point of contention. I soften it a little bit in the book, but that's still not popular in my family. Over the years I've tried to be more sensitive. And yet I still don't think you send your kids off at 12 or 13, the way my grandparents did, if you have the wherewithal to support them.

There's a scene in my book where my brother's black friend is not made welcome by someone in my family, and people may be unhappy about that. We've had a lot of these discussions before. Once I started reengaging with my family, we revisited some of it. I am struck by the extent to which I probably acted like an entitled know-it-all, or a superior, self-righteous little ass, throughout my teens and 20s. Hopefully it wasn't much longer than that. I understand things differently now.

I’m sure you know that anecdote by the novelist Mary Gordon, who describes going to her father’s funeral and having one of her aunts, who was a nun, come up to her and say, “Mary, you know we all hated your book.”

My father really wanted to be a writer, and at a certain point he said to me that what stopped him was this very Irish thing, where he always heard a voice in his head saying, "Who do you think you are?" Right after he died, that Mary Gordon essay ran, examining the relative lack of accomplished Irish-American writers. She literally says it's that voice: Who do you think you are? There's a lot of that.

You write about the fact that your father was the first person in his family to go to college, and also about the fact that he remained a liberal Democrat when many others around him didn’t. Both of those things describe my father too, and many other people. This is a tricky thing to discuss, but what’s the connection between higher education and voting for Democrats?

Sticking to my father's family, the three boys who went to college, all because they went away to religious orders, turned out to be Democrats. The three siblings who didn't turned out to be Republicans. When I've said that before, it can sound like I'm saying, "Oh, the smart ones became Democrats," and I'm not saying that at all. What I realized writing this book was that liberalism in my family could seem like a form of class privilege. We were in the suburbs, we were isolated from the changes in New York. Of course my values are firmly held and my father's were too. But it's easy for us to think that integration is great and school busing is great, because those things did not affect us, by and large.

But that division is very important. Obama's real problem right now is not exactly with working-class whites. That's shorthand for a lot of things. It's really with non-college-educated whites. Those are the people in our society who feel the most besieged, and in every poll they're the most pessimistic about their chances and the chances of their kids. Somehow, for a lot of complicated reasons, they've come to associate their problems with what the government has done for other people but not for them.

You know, on the left we often talk about the absence of social class in the American conversation, and no doubt we should talk about that more. But I've come to believe the division in this country is often more a system of cultural castes that is not purely economic.

Yeah, I agree. It's cultural caste and it's isolation, including self-isolation. You often hear this about isolated black neighborhoods, but it can be just as true about isolated white neighborhoods, where people never go into the city and live in a lot of generic fear. And when you don't go to college you're just not exposed to different ways of thinking and different people. Even if you go to an all-white Christian college, you're likely to come away with somewhat different attitudes than if you never do it at all.

On the subject of white people, one who’s been in the news a fair bit lately is Paul Ryan. Obviously he comes from a very different social background than Mitt Romney. But he’s been proclaimed as “working-class” by many commentators, and you dispute that.

Absolutely. He is a child of privilege and comfort, born into a construction business run by his family in Janesville, Wis. I think Paul Ryan is a great example of what drove me to write this book. It has been so vexing to me, and so mysterious, that wealthy or upper-middle-class white people, especially Irish Catholics, have become the face of the white working class when they never spent a frickin' day in the working class in their lives. And that goes for Bill O'Reilly, Sean Hannity, Pat Buchanan and Paul Ryan. Ryan's not as associated with the racism and the really nasty stuff, but his politics are just as nasty. His beliefs and what he wants to do are just as divisive and damaging.

But without irony, last weekend we saw him hailed as the white working-class addition to this ticket. And again, it works. I think it works in part because the media is so removed from any kind of working-class roots themselves that they don't think about what that means. What that has come to mean is not that you lack a college education and work your ass off doing manual labor. It's come to symbolize being closed-minded about abortion, being hyper-pro-military, being religious, being culturally very conservative. It doesn't have any class content at all.

How much does the Romney-Ryan ticket represent a doubling down on whiteness? You can’t get any whiter than those two guys, and I don’t just mean their skin color or cultural background. They both seem like people with no experience of diversity, no relationship to the changing nature of America.

I think the Republicans doubled down on whiteness, and I think they have a problem. It could be a winning strategy, temporarily. They are making decisions that, well, it's not great that Latinos and Asians don't like us, but we have to double down on that base. This could get us through 2012, and we'll worry about 2016 later. I would think that, as a Republican, you would think it's a problem that nine out of 10 self-identified Republicans are white, in a country that's about 60 to 62 percent white right now. One of our two major parties is a white party! It's not named the white party, and I'm not going to call it a white supremacist party. But it's the white party, and they don't seem to give a damn about that. I think that's a demographic and political and social disaster.

In the long game, they probably still have a shot at Latinos and Asians. If the people in the Republican Party who are not racists come together and say, OK, we have to write off African-Americans for a while, but we're really going to make a play for these other groups -- I mean, they have to do that. Otherwise, it's demographic extinction. But for 2012, their only hope is to double down on whiteness and play Paul Ryan’s "makers and takers" card.

So in telling the long and complicated history of how American working-class whites became the Republican base you go pretty far back into history. One of the things you start with is Bacon's Rebellion in 1676.

Bacon's Rebellion was basically English, Irish and black indentured servants -- the slave codes hadn't been enacted yet -- rebelling against the colonial Virginia elite. You realize really quickly that there are no pure good guys in any of these stories. Bacon's Rebellion is always hailed as the first multiracial coalition in American history -- you know, Howard Zinn loves it! Well, they really came together to fight the Indians. That part maybe isn't so ideal. But this was what the colonial slave-owning masters really feared. They had imported not just Africans, but indentured servants from Britain and Ireland, creating this army who, if they banded together, could topple the power structure. So they created the slave codes, which made Africans slaves for life. They started enforcing the terms of indentured servitude, which meant whites could be free in seven years, you got a gun, you got some grain. You were given white status, basically -- and even if most people didn't get those things, there was the idea that you would get them. They made intermarriage between whites and blacks illegal. They went to a lot of effort to make sure that people didn't see what they had in common.

So you would agree with one of the central analytical points about American history as seen from the left, that it’s a long history of elite groups finding ways to pit workers of different races against each other, as a way of holding power.

I think that's pretty accurate. I think it's a way that people in power keep power. It's obviously something in human nature that we're susceptible to, whether it's people at the top or at the bottom. It must play to something not so great in our natures, that we're easy marks for that kind of divisiveness. Now, it's not a conspiracy -- it's not like the Koch brothers have been handed tablets that have come down over the centuries. It only looks that way!

And then there's the darkest moment in the whole history between African-Americans and Irish-Americans, which was the New York City draft riots of 1863. You draw an interesting parallel between those terrible events and the inner-city rioting of the 1960s.

Yeah, I really wonder how many people know about that. That began when a lot of Irish Catholics who were drafted during the Civil War rebelled against it.

Many of them were fresh off the boat, and felt they had no dog in the fight.

That's right. For one day, it was essentially a workers' riot, with Germans and other immigrants involved. Then it became a religious riot and -- sadly, tragically and horrifically -- a race riot. [At least 100 African-Americans were murdered by whites.] It was vicious. Now, there were places where Irish people protected black people, and in the black-Irish downtown neighborhood there were no murders, but for the most part it was an act of despicable savagery. You can’t excuse it, but it has to be understood as the desperation of people at the bottom who are being pitted against this other group at the bottom, and being told that this other group is above them: "You're going to go fight for them."

To the “whiteness studies” people [in left-wing academia], this was the Irish trying to prove that they were American, but in fact it postponed the Americanization of the Irish by at least a decade. The words that were used by the New York Times and other thought-leaders of the day was that the Irish were animals, they were savages. It's so striking that almost exactly 100 years later, when African-American neighborhoods began going up in flames, my family and many other people used those words to describe black people: animals and savages.

Sure. Many white people all across America used that language, I'm afraid.

Almost no one saw the correspondences, almost no one said, "Hey, that's what we were called." There was no linking of the two things, yet before the Watts riots [in Los Angeles in 1965], the largest civil insurrection in American history was the New York City draft riots, with the Irish playing that role. To left-wing groups, the draft riots are a despicable act of savagery and racism, and to right-wing groups the '60s riots were a despicable act of savagery and destruction. There's no conversation that bridges the two.

Where did your personal and political interest in race come from? People who know you from TV may not know this, but race relations and racial justice and the intersection of race and economics have been enduring issues throughout your career.

Well, I don't think I was even in kindergarten when my father started discussing the civil rights movement with me. For both my parents, that was the moral issue of the time. We watched it all on TV -- the fire hoses and the dogs -- and we were horrified. One day when we were alone, my father explained to me that we were "black Irish" and that meant we were possibly descended from Spanish or Moorish invaders, with dark hair and hazel eyes as opposed to the redheads and blonds. We should not look down on "those people" because we might be them. I never thought that I was black or that I would suffer discrimination or anything.

This is not you explaining that you're really black.

No, this is not my way of explaining that I'm actually black. I have tried! I don't get very far, so I gave that up a long time ago. I'm not, and it didn't enter my consciousness that way. It was "do unto others," in a really vivid rendering. I just continued, even after it was no longer fashionable, to think that racism and particularly poverty were the moral issues of our time. Ironically, I've lived in California for more than half my life, and California is really complicated for the black-white racial paradigm. It doesn't really work there. Certainly in San Francisco, where you can see the black school superintendent clashing with Chinese parents, or in Oakland, where we had black and Latino parents sparring, it became clear to me that there was not going to be this natural people-of-color coalition that would transform American politics. Strife is the natural state, and we're all tribal to some extent.

We need models of cooperation and a social future that don't rely so much on race, and do not view whites as always being the people on top, the oppressors, the haves. The inability to parse the meaning of what it means to be white today -- nobody was even trying to do that. The same impulses that caused me to be concerned about racial justice for black people caused me, later in life, to become more sympathetic to white working-class people and poor people. For those people to be told that they have white privilege, that there's never a situation in which they are the underdog, that's preposterous.

You write that when you first became a TV commentator, you were aware of the fact that your white working-class background was, in effect, a card you could play. But then, as you started doing it, the role became real for you. Is that fair?

Yeah, I think that's true. The impulse to describe myself as a working-class Irish Catholic was there, and I recognized that it gave me entree to the debate. It shocked people.

Right. Being a San Francisco liberal doesn't carry the same cachet.

No, it doesn’t, for better or worse. And then, increasingly, I felt I was speaking for people who otherwise were being represented by Pat Buchanan or Paul Ryan. It's a stretch to call me working-class, although my mother and father were both very much working-class, or even poor. By the time I came along, we lived in Flatbush [a Brooklyn neighborhood of modest single-family houses] and my dad had gone to college, and the rest of my life was a steady, lovely climb upward. My cousins are very much working-class, they work for Con Ed, they are cops, firefighters, steamfitters, teachers. So there really weren't a lot of people like me in that debate.

In the book, I write a lot about the experience of the 2008 Democratic primary campaign, where I felt that white working-class people voting for Hillary Clinton was exclusively explained in terms of racism, and I didn't think that was true. Do I deny that some of it was racism, maybe a lot of it? No. But there was a lot more, and I thought it was unfortunate that debates about the two candidates' economic policies were completely lost in charges of "You're racist" and "You're sexist." It felt like going back to the '60s again for a while.

That was a pretty hot and heavy campaign, and you don't completely excuse yourself of all possible misdeeds.

No. As much as I wanted people to understand that the white working-class vote for Hillary represented class interests, I was also caught up in the first lady-president thing. I was shocked by that! I would have told you that didn't matter to me at all. I didn't start out supporting Hillary, but that became my own kind of tribalism. I felt that people weren't really acknowledging her historic dynamic, and my tribalism got engaged, and that's almost never a good thing.

You know, I really felt for Geraldine Ferraro, even though every time she tried to explain what she said it got worse and worse. And there was that crazy woman, Harriet Christian, screaming that Hillary had been robbed by an "inadequate black man." I included a paragraph in a piece where I tried to explain what she meant, and there was really no explaining it. That particular cry from the heart -- I should have left that alone, and explained how I felt. There are people to this day who, if they want to say that I'm a racist, point to that one paragraph I wrote about Harriet Christian. So I apologize. I was wrong.

There are so many historical benchmarks along the way, from Bacon's Rebellion and the draft riots and onward. In more recent times, we have Lyndon Johnson signing the Voting Rights Act 1965, New York City's white ethnic voters rejecting civilian oversight of the cops in 1966, and then the Democratic Party blowing itself up in 1968, when the white working class crosses over to vote for Nixon. Is that a very rough outline?

Very rough but largely accurate. But one thing I didn't realize was the extent to which a lot of the white working class, especially Irish Catholics, left the Democratic Party much earlier. Some of them left with Al Smith [the Democratic presidential nominee in 1928]. The Al Smith story fascinated me!

Al Smith is a fascinating figure in American history. More than a footnote, but less than a whole chapter. First Catholic politician on a national scale; first Catholic presidential nominee.

Right. He attracted black votes, he began to put together the New Deal coalition by keeping Southern whites but beginning to attract both Southern and Northern blacks. His defeat was an incredible victory for nativism and anti-Catholic prejudice, and a lot of Catholics didn't recover. So when he didn't get the nomination four years later, and it went to that Yankee aristocrat Roosevelt, the Irish mistrust of the elite was catalyzed. They were putting us down again! Pat Buchanan's father left the party at that point, and some people in my family left the party. I had always believed that everybody voted for Kennedy on both sides of my family. But a lot of them had voted for Nixon -- in 1960! They had also been pulled away by Joe McCarthy, another sad moment, and by profound fear of Communism. In some ways that's reassuring to me.

You mean because it wasn't just about race.

Exactly. It predated the civil rights revolution, and a lot of it had nothing to do with race. Yet there's no way that the turmoil of the '60s wasn't a large part of it. Because the white working class came back to Lyndon Johnson in 1964, and they remained in play, let's put it that way. And then the party split itself in half in '68. When Hubert Humphrey becomes the face of reaction, the guy who introduced the civil rights plank in 1948 -- when he becomes the worst collaborator with Republicanism and imperialism that we have, you have a problem.

You and I have had that conversation before, and I'm somewhat sympathetic to that point of view from this historical distance: the idea that when the left turned away from Humphrey in 1968, it was a moment of tragedy and lost opportunity. But given everything that had gone wrong -- the assassinations, and his fatal association with Johnson’s failed presidency and his refusal or inability to speak out against the Vietnam War -- I still can't see how it could have turned out differently.

One thing I try not to do, which at times is unsatisfying, is to go back and say, "This is what should have happened." I'm really looking at what did happen. We live with this complicated and awful legacy and what do we do with it now? If I could have voted back then -- I don't know. My father did vote for Humphrey, somewhat reluctantly. Had I been a voting-age person back then, I very well might not have. The antiwar movement was on the right side. Those movements were necessary, and probably a lot of the chaos and falling apart was necessary too, because society's coherence was based on a lot of things that we couldn't tolerate anymore. It was natural that we pulled it apart, and the question is, how do we come back together? The Obama coalition was a first step, but we still haven't done it.

You know, I was on the floor of the Republican convention in 1992 when Pat Buchanan made that famous speech about the "cultural war" in America, and I still think that was a moment of twisted brilliance on his part. You and I may feel that he's on the wrong side of that war, but he correctly perceived that the people you're writing about feel themselves cut off and divided from the mainstream of American society, especially the educated, multicultural people on the coasts and in the big cities. Moreover, they're right to perceive themselves as being on the other side of a caste divide, and nobody really knows how to bridge that gap.

Absolutely. It took us a while to get here, and it's going to take us a while to get out. We can start by talking about it differently, using less divisive language. Not writing them off, even if we can't win them back. It made me nervous in 2011 when there were stories about how Obama could win without Ohio. They're not talking about that anymore, and remember that Obama won the white working class in Ohio. He didn't win it nationally, but he won it in Ohio. It wasn't as though the "Hillary voters" were unreachable, or unable to see what he offered versus John McCain. And I think they'll be able to see what he offers versus Mitt Romney and Paul Ryan. The way we sometimes congratulate ourselves on being the Obama coalition -- you know, we're younger, we're fun and flirty, we're colorful, we're on Twitter! -- there's no place there for 50-somethings who've lost their jobs and will never get the same kind of job back, and who can't afford college for their kids. I think there are ways to talk about these issues that should give us a better chance than when we're fighting on a culture-war level.

I think the president has begun to talk about it that way. You know, in the 2008 campaign, the hope and change stuff -- "We're the ones we're waiting for" -- had an edge of elitism. I don't believe Barack Obama is an elitist, but the campaign could take on the fervor of the better class of people doing what's best for America, and that's never good. Those were the times I was worried, and I'm not seeing that in the 2012 campaign.

One thing I talk about a lot in the book is the idea of the golden age that never was. We made the political decision in this country to create a middle class, out of fear of communism and domestic unrest and fascism. The powers that be decided that it was better to flatten income and inequality, to have a 90-something percent top level of marginal taxation. There were engines of the middle class -- mortgage insurance, highway construction, public universities, college funds -- and those were political decisions. One problem is that people don't see them that way, and another problem is that they didn't help nonwhite people nearly as much.

This great apparatus that created the middle class excluded black people for a long time, and the suburbs had restrictive covenants, where certain people couldn't buy even if they had the means. So we left a lot of people out, and all these white people got a lot of help. Government made all these decisions to help people that were colorless and odorless, and just seemed to be the background, like the air in this restaurant. People didn't even identify them as government help, and then you get a situation where minorities say, "We didn't get what you got," and white people say, "We didn't get anything! We worked for everything we got!"

It’s a fundamental divide of understanding, where you really need to change the terms of the conversation. And that's where I think the president has been brilliant. There's a new debate, where we have to recognize all the things government did to make an earlier generation of success possible. We stopped doing those things 20 or 30 years ago, and we have fallen into a horrible economic and social decline.

Another fascinating tangent in your book is the material about Daniel Patrick Moynihan, who himself grew up in poverty and later became this controversial sociologist and then a U.S. senator. When I think about Moynihan's recommendations to LBJ in the mid-'60s, urging a New Deal-scale public employment project to lift poor African-Americans toward the middle class – well, if that had been done, we'd be living in a different country today.

I completely agree. Moynihan once proposed that we have twice-daily mail delivery, to add hundreds of thousands of new jobs, and here we are talking about slashing the Postal Service. He understood that jobs were money but also that jobs were social fabric, jobs were pride. I fret about how much I praise Moynihan in this book! I know that someone is going to come up with something he said sometime --

His language can sound patronizing or paternalistic.

Right. But I think that's a really important moment, when Michael Harrington and Moynihan are in the Labor Department and they're proposing this massive public works project. It gets rejected because Johnson is spending billions of dollars on the war. If those recommendations had been adopted, I think things would have been very different. I defend welfare, but the idea that we were going to let society's most marginal, vulnerable people live on welfare, raise their children alone and not have to work -- first of all, it led to incredible isolation, and second of all, it was never realistic. As women from all other classes were surging into the workforce, whether they wanted to or not, the way we administered welfare at that time was a recipe for social resentment and all kinds of unintended consequences.

So, yeah, put me down for a massive public employment program back in 1964, or in 2012. We're not going to solve these problems without looking at government as the employer of last resort, and we are at last resort. African-American teen unemployment is ridiculous. These problems are just as urgent as they were then. Some of the solutions are the same, and some are different. And my last word about Moynihan is that everything he said about black people he also said about his own people. He knew that we had been on the bottom and had colluded in keeping ourselves on the bottom to some extent. Poverty, oppression and nativism had forced the Irish into ghettoes, and some had a culture of poverty that made things worse.

This is tricky to talk about, but it would be great if we could: The way that African-American poverty is on a continuum with white immigrant poverty. Some people will argue that Moynihan had no business opining on the problems of African-Americans, and that’s problematic. He did so fully believing that he could do it because his people had the same problems. If we can't talk about that and see the common bond, we're screwed.

You make a persuasive case, in many ways, for supporting President Obama and the Democratic Party – and you know how difficult it is, on a personal level, for me to say that! But how do you respond, at this point, to what we might call the Glenn Greenwald issues? The expensive and dubious overseas military adventures, the drone assassinations, the erosion of constitutional liberties – all the stuff from the Bush administration that we thought would go away and mostly hasn’t.

You know, I'm very disappointed on all of those fronts, and to some extent on economic fronts as well. When we're talking about why the white working class left the Democratic Party -- well, the Democratic Party left the working class around the same time. The Democratic Party drew the conclusion that government was being blamed for all these problems and so they were no longer going to be the party of government. They moved away from economic populism and greater inclusion, and they began courting business. They ceded the argument to Republicans, they joined the deregulation brigade, they signed on to the argument that entitlements are a problem and we've really got to cut Medicare and Social Security.

So the Democratic Party was no longer the party of working-class people and working-class ideas. There are lots of reasons to be unhappy with the Democratic Party and Barack Obama. I'm just stuck being a "lesser of two evils" person. In Chris Hayes' book "Twilight of the Elites," he argues that progressives are divided into institutionalists and insurrectionists. I'm such an institutionalist! I still call myself a Catholic, because they're not going to drive me out. I call myself a Democrat because the DLC is not going to drive me out.

I don't think Mitt Romney is going to change any of the civil liberties policies that I find abhorrent. The only thing for the left to do is build up its strength, and organize at the congressional level and the local level. We have obviously not been successful in building our case that this kind of continued military adventurism makes us less safe, and that we can afford a different way. Trashing Barack Obama is not the way to win people over to our side. On those issues I am really disappointed, but having him go away in January wouldn't make anything better for anyone.

Shares