REYKJAVIK, Iceland — There are three main buildings that comprise the Reykjavik Art Museum, but because of my limited time in the Icelandic capital, I chose to visit Hafnarhús, as it houses the most contemporary selection of all three.

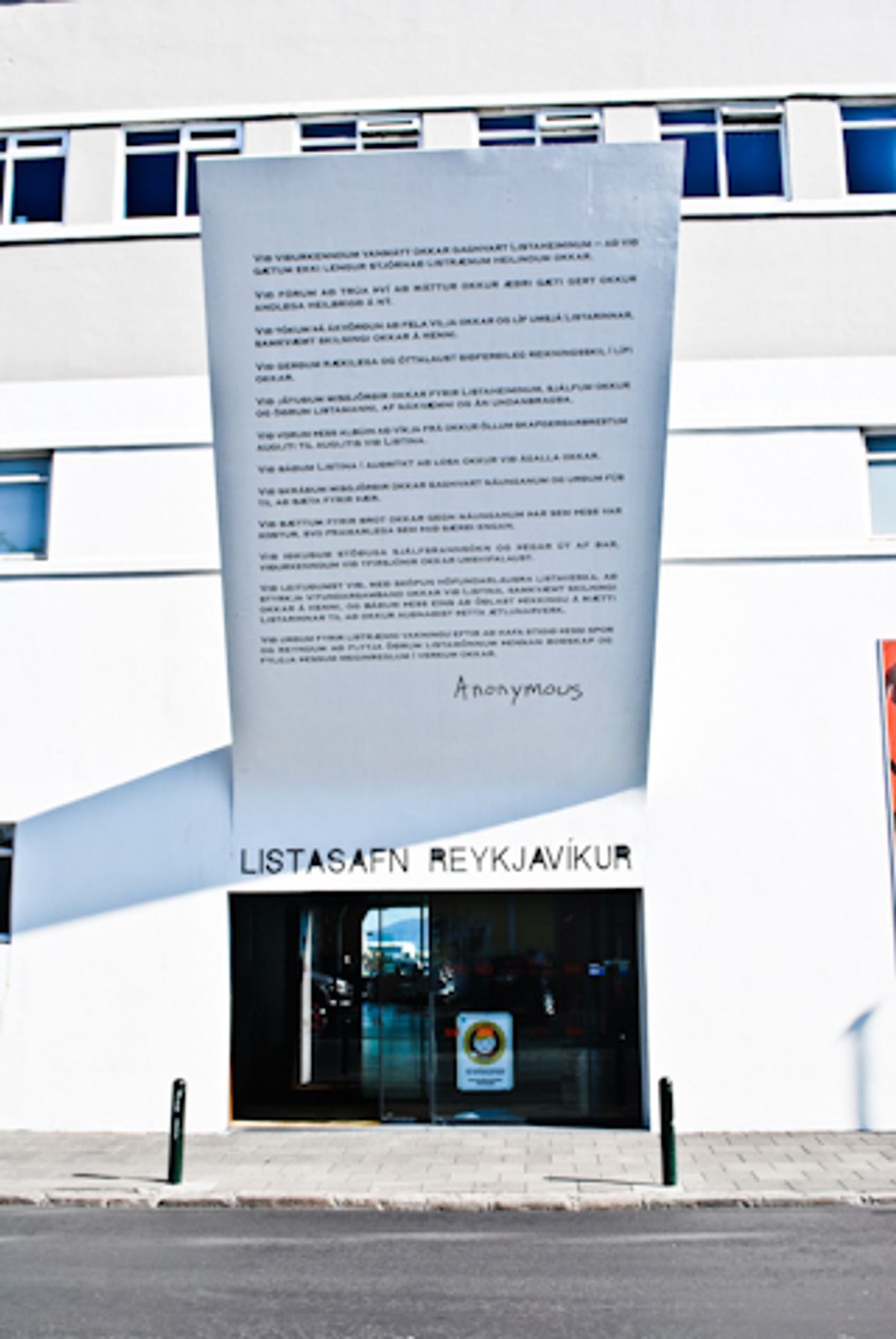

The building from the outside is rather bland, except for the awning, which shoots out over the main entrance. It's covered with the 12 steps of Alcoholics Anonymous transformed into a type of artist’s manifesto — what better way to begin a museum visit? Inside, however, was a modern interior with cool steel walls and a great selection of contemporary art.

The first galleries I visited were of the Erró – Drawing exhibition, which runs until August 19. Best known for his comic-inspired imagery, Erró’s exhibition featured a wide range of paintings, drawings and even sculptures from as early as the 1940s until today. His large paintings were by far my favorite, but I also enjoyed his teapot series where he transfers his style onto Chinese porcelain. The result of his teapot experiments was an obvious but playful blending of fine art and design. It was great to see the range of work that evolved over Erró’s artistic career, and it’s worth noting that it was a well-curated show.

(I)ndependent People

As part of my visit, I was really excited to see the (I)ndependent People: Collaborations and Artist Initiatives, which runs until September 2. Focusing on Nordic artist collectives, groups, galleries and other collaborative works, the show explored what new forms can come from collaborative processes. The first gallery I explored was the Leyline Project: Steingrímur Eyfjörð and Ulrika Sparre. Ley lines are a pagan geo-spiritual belief that certain locations have more energy or power embedded in them where Ley lines intersect, a type of Feng Shui for the planet.

I was taken by this show because it had hints of Robert Smithson, participatory art, 1960s performance art and Op-art, while feeling distinctly Nordic. As my introduction to an Icelandic museum, this sincere exploration of old Nordic traditions and contemporary art was a great start.

The next gallery was a collaboration between artist duo Nomeda and Gediminas Urbonas and MIT 4.333, a group of MIT students. The collaboration created interactive art that confronted how we view work and experience space while using military surveillance technology as their medium. One untitled work (pictured above) recorded viewers’ feet and played them back randomly as I looked at the part-screen, part-mirror installation. Watching my feet become one of many ghost-like forms on the screen created an anonymous yet connected feeling of viewership that I hadn’t considered much in all of my visits to museums. It reminded me of Tom Friedman’s “1000 Hours of Staring” (1992–97), where the work’s original form is added to by the process of viewership.

The most overtly political section of the (I)ndependent People show was a gallery given over to the Kling & Bang gallery and to Jóna Hlíf Halldórsdóttir & Hlynur Hallsson. There was a dizzying array of artists involved with this large space, and much of the work changed over the course of the show. There was a relational aesthetics–inspired raw wooden platform with tables, books and pens where artist talks, debates and conversations were being held throughout the duration of the exhibition. I wish I had been there for one of the conversations; finding myself alone in a relational installation felt pointless.

Halfway through my trip, I took a break in the small museum cafe, which was nothing if not adorable. Antique Icelandic furniture and quaint porcelain plates and milk holders rested against the stark steel walls of the museum halls, and it was a sight to behold. I didn’t travel to Iceland for super contemporary modernist architecture and purely theoretical art that I could easily find in mega-cities like New York or London. The glimpses of local Icelandic flavor appealed to me.

The final work in the (I)ndependent People was “Knitting House” (2012) by Elin Strand Ruin + The New Beauty Council. When I first entered the raw industrial space, I perceived it as a post-minimal textile installation. But once inside, you realize it is in fact a fabric replica of a typical Western postwar apartment complex. The work was really enjoyable to walk through. The combination of the common craft (from what I have discerned from my time in this country, it appears that all Icelanders knit) and installation art at a large and detailed scale was impressive.

Inside “Knitting House”.

Inside “Knitting House”.Yet my favorite work in the entire museum was the large video projection “The Palestinian Embassy” (2009), by Goksøyr & Martens, which was also part of (I)ndependent People. Even as much of the future of Palestinian land and identity is debated by powerful figures all over the world, the idea of Palestine remains abstract in many of our lives. This “embassy” was a hot air balloon flown over Norwegian locales while carrying Palestinian politicians and academics aboard. As the conversation has been in the air for years, so to speak, the metaphor of Palestinian diplomacy and politics took on a very physical manifestation in this aerial work. The discussions that took place aboard were recorded and transmitted below. This is such a moving piece, both poetic and beautiful, but also deadly serious and needed.

My short stay in Reykjavik was surprisingly packed in a city of only 120,000 inhabitants. It was great to find a small city teeming with art and culture at every turn. The quality and range of work and curatorial finesse would easily feel at home in any major museum in the West, but the combination of the traditions of Scandinavia with a very contemporary and local dialogue enlightened me about Iceland’s unique perspectives on contemporary art. If you are in Iceland now, or plan on visiting, this is definitely worth a stop.

Hafnarhús is one of three different buildings that make up the Reykjavik Art Museum. Hafnarhús is located on the city’s waterfront. It is open daily from 10am to 5pm and Thursdays from 10am to 8pm.

Hailing from Indiana, Ben Valentine moved to Brooklyn a year and a half ago. Now working for Tara Donovan and Allan McCollum, interning for Creative Time and Hyperallergic, Ben has immersed himself in the contemporary art world. Ben is interested in public art, the internet's potential and in learning how to write and think about art without becoming a snob.

Shares