I doubt that any other American author could have generated the overwhelming and almost universal response that erupted when Ray Bradbury died last June at the age of 91. Even President Obama issued a statement that the news “immediately brought to mind images from his work, imprinted in our minds, often from a young age” — one of the few times I can recall an American president mourning the death of an author since John Kennedy commented on the death of Hemingway. And Obama may have put his finger on something by noting that Bradbury’s stories were “imprinted” on us even as children. Certainly some of Bradbury’s stories — “The Pedestrian,” “The Veldt,” “Homecoming,” “There Will Come Soft Rains,” “The Million Year Picnic,” “All Summer in a Day” — are among the most reprinted in the English language, especially when one considers not only Bradbury’s famous recycling of his own material in different collections but also the various science fiction anthologies, literary short story compendiums, and — perhaps most important in terms of this point — the various middle-school and high-school textbooks and anthologies that for decades made it seem almost impossible to avoid reading at least one or two Bradbury stories if you were receiving a public education anywhere in the U.S. Bradbury may have been the ideal middle school writer — accessible, enthusiastic, provocative, and offering an almost irresistible helping of lucid and luminous prose. On more than one occasion, he claimed to friends and interviewers that he was really a children’s writer, although during the height of his career only one book, Switch on the Night (1955), was published as a children’s book; the young-adult repackagings of stories R Is for Rocket and S Is for Space came later, in the 1960s, and The Halloween Tree not until 1972.

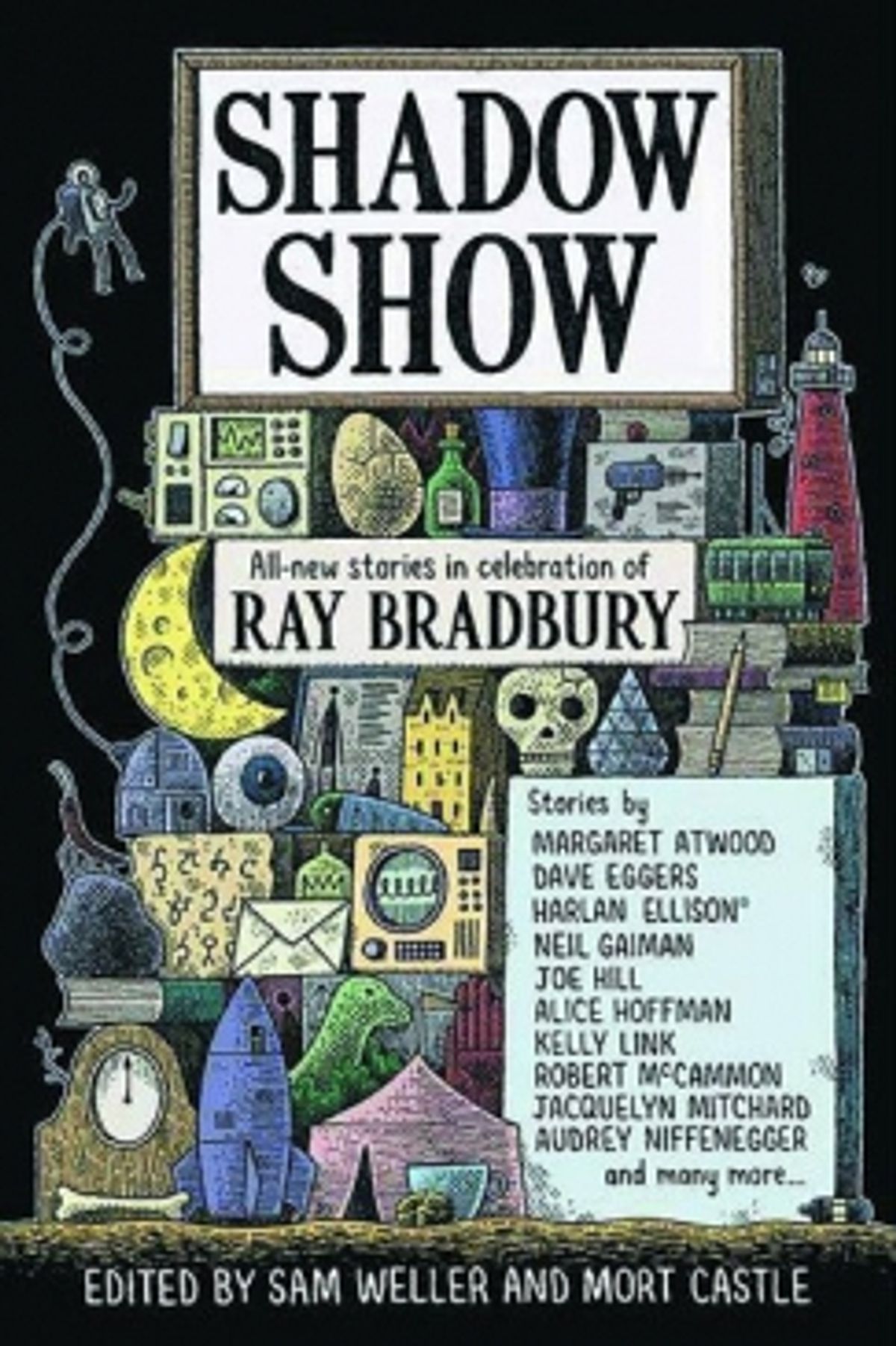

In other words, Bradbury may well have been the last American writer whose works can be said to have informed nearly all our childhoods, a point that is reinforced by the impressively diverse range of contributors to Shadow Show: All-New Stories in Celebration of Ray Bradbury, Sam Weller and Mort Castle’s generous tribute collection, assembled only a few months before Bradbury’s death. Weller and Castle asked each of their 26 contributors to provide a brief afterword to their stories, and almost without exception they recount anecdotes of their teen or pre-teen years when they first encountered Bradbury on a spinning rack in a school library (Kelly Link), or in a grade school class (Dave Eggers), or in the SF section of a public library, or “when I was no more than eight years old” (Ramsey Campbell), or when “I was eleven or twelve years old” (Joe Meno), or “by the time I was ten or eleven” (Dan Chaon), or “as a teenager” (Margaret Atwood). These are testimonials to the kind of imprinting that Obama spoke of, and while a few of the contributors mention revisiting Bradbury years later, as adult readers, it seems evident that roughly eight to fifteen is the prime age for getting the Bradbury bug. This is reinforced further by the remarkably vivid memories that nearly everyone, myself included, seemed to effortlessly dredge up when hearing of his death — not only the first book or story we read, but the precise visual image of where we found it and when. In my case, it was a Bantam paperback of "The Illustrated Man" in a thrift shop with a table of tattered books.

This raises another point that recurs almost invariably in the afterwords to these stories: nearly all the Bradbury stories cited as being formative by these contributors were originally published prior to 1962, even when the writers, like Kelly Link or Dave Eggers, are comparatively young. This seems like a natural break point in Bradbury’s career, the year "Something Wicked This Way Comes" was published, the year Bradbury began repackaging his earlier stories for young adults with "R Is for Rocket," less than a year before the Magazine of Fantasy and Science Fiction published its special Ray Bradbury issue, with its retrospective, if not quite valedictory tone. The fact is that, despite a couple of later important collections ("The Machineries of Joy" in 1964 and "I Sing the Body Electric" in 1969), Bradbury’s most lasting work had been done by then. It’s also a convenient date for marking the transition between Bradbury’s career as a science fiction and horror writer and his emerging worldwide reputation as a master of the literary short story. He had begun publishing in “slick” magazines by the end of the 1940s, and — according to Jonathan Eller’s fascinating recent biography "Becoming Ray Bradbury" — had energetically lobbied against Doubleday featuring the “science fiction” label on "The Martian Chronicles" and "The Illustrated Man." By 1962, he had indeed “become” Ray Bradbury, his identity as a writer no longer constrained by his pulp origins, his influence no longer confined to, or even particularly forceful in, the SF and fantasy community.

And that broadening of influence is also much in evidence in Weller and Castle’s anthology. I have no way of knowing which writers were solicited for contributions, but it’s telling that among the final selections the only name widely recognizable as an SF writer is Bradbury’s longtime friend Harlan Ellison, whose contribution is also the shortest in the book — a dark, eschatological tone poem followed by a longer anecdote that recounts Bradbury once telling Ellison they were actually brothers, because their literary parents were the married couple Edmond Hamilton (one of the great space opera writers of the pulp era) and Leigh Brackett (who had been one of the young Bradbury’s first mentors). Few would consider Ellison and Bradbury as close siblings in any literary or stylistic sense, but at the same time Bradbury had a point — there’s some of the genetic material of those old pulp classics in both writers.

But such are the mysteries of literary DNA. Those old retroviruses can express themselves in unexpected ways generations later, and Bradbury was a carrier. He may have read Eudora Welty and Willa Cather and imported some of their stylistic grace into genre fiction, but by the same token he passed along some of the imaginative energy of Brackett or Henry Kuttner to the writers who followed him. Horror writer Thomas Monteleone recognizes this directly in “The Exchange,” in which a thinly disguised teenage Bradbury meets an even less-disguised (and sentimentalized) H.P. Lovecraft and concludes they’ll have “much to discuss.” It’s fairly thin as a story, but makes its point. Or, if it weren’t for that ancient DNA, why would Kelly Link — arguably one of Bradbury’s true heirs in that her stories have consistently seemed as odd and distinctive as Bradbury’s did way back then — cast a recognizably Kelly Link story within the framework of a decades-long space voyage, in which the characters talk in the sensory-nostalgia language of Bradbury characters: “’Bread, fresh from the oven! ... and old books,” or “A whole grove of orange trees, all warm from the sun, and someone’s just picked one. I can smell the peel, coming away.” They decide to tell each other stories, and the kernel of the tale lies in one of these, about a former boyfriend raised in one of two identical tacky American ranch houses built as an art installation on a vast British estate. While the frame parallels the told tale (there were originally two identical spaceships, though one has disappeared), the hypnotic mystery of the story makes you wonder if the sudden narrative turns that Link is famous for might be an example of the late expression of that archaic DNA.

If Link’s is one of the most intriguing stories in the anthology, another — and easily one of the best — is Alice Hoffman’s “Conjure,” which begins by placing us firmly in late-summer Bradburyland: “It was August, when the crickets sang slowly and the past lingered in bright pools of glorious light ...” As in Dandelion Wine or "Something Wicked This Way Comes", two 16-year-old friends, Abbey and Cate, are facing the end of summer and the end of their own childhoods, while holding on to the local library as a source of psychic stability. When the bad-boy cousin of a neighbor arrives in town, the story somehow seamlessly moves from Bradbury territory into Alice Hoffman territory, and is the best example in the book of how the Bradbury ethos can inform the most nuanced literary fiction. One reason this works is that Hoffman doesn’t shy away from the dark side of Bradbury’s nostalgia, a feature shared by some of the other best stories here. Dan Chaon’s “Little America,” for example, is a grim tale of a boy apparently being abducted by a sinister adult in a brutal post-apocalyptic America — until we learn the boy’s true nature and the abductor’s true motives. There’s virtually no echo of Bradbury-style prose here, but there’s an acute understanding of the sensibility of a strange child in a strange and violent world (there’s a good deal more violence in Bradbury than most people remember, although it became more implicit as his career matured).

In fact, if there’s one thing that the contributors to this generally fine anthology seem to have been consistently aware of, it’s that mordant, sometimes ironic side of Bradbury’s famously summery imagination. Some of the stories echo Bradbury only to the extent that they might well have appeared in some of the same markets Bradbury sold to in the 1950s; both Margaret Atwood’s “Headlife” (which she modestly but accurately describes as a “little riff”) and Jay Bonansinga’s “Heavy” offer the kind of twisty endings that Ellery Queen’s Mystery Magazine once specialized in — Bonansinga’s is little more than a punchline — while Dave Eggers’s "Who Knocks?" or John McNally’s “The Phone Call” might have been comfortable in a 1940s issue of Weird Tales. The one planetary tale, Joe Meno’s “Young Pilgrims,” about a religious colony, is probably a bit literary for the old Planet Stories, but that venerable pulp, which had no problems with Bradbury’s version of Mars, might have been the only SF magazine that would let Meno get away with howlers like “he could taste the nitrogen inside the helmet” or “white light filling the space between his flesh and joints with a decided ferromagnetism.

The contributor who seems to have most fully internalized the discursive space of the early Bradbury is Joe Hill, whose "By the Silver Waters of Lake Champlain" combines elements of "The Lake" and The Foghorn, along with sly references to other Bradbury tales such as “Kaleidoscope,” achieving the same sort of haunted sense of loss at which Bradbury was so expert. A similar sense of loss, but of an entirely different sort, is the focus of Neil Gaiman’s “The Man Who Forgot Ray Bradbury,” in which the words gradually draining from the narrator’s memory are pointedly evocative of Bradbury’s preoccupations with the death of writing. Almost as successful at this manipulation of Bradburyesque materials is Bonnie Jo Campbell, whose “The Tattoo” riffs inventively on "The Illustrated Man" while alluding to other Bradbury tales in the moving tattoos that the hapless protagonist ends up with; and Julia Keller’s “Hayleigh’s Dad,” a tale of childhood friendship that turns dark in the manner of some of Bradbury’s atmospheric early horror tales. One of the more substantial and impressive tales, Lee Martin’s “Cat on a Bad Couch,” deals with an immigrant neighbor in a way that clearly echoes Bradbury’s sole New Yorker story, “I See You Never.”

Since Fahrenheit 451 is almost certainly Bradbury’s ideologically most important work, it’s a little surprising that few of the contributors chose to venture into that dystopian territory. Gary Braunbeck’s “Fat Man and Little Boy” is set in a world in which the obese are forbidden to leave their houses, but that’s a pretty unconvincing premise, and the story itself focuses more on the grotesquerie and insouciant voice of the title character. Bayo Ijikutu’s “Reservation 2020” depicts a grim urban future in which segments of the population are segregated into “compounds”; its sometimes awkward exposition is redeemed by its streetwise narration, and it may be the most uncompromising story in the book. Charles Yu’s “Earth (A Gift Shop)” depicts a near-abandoned future Earth trying to drum up business in a breezy and insouciant, but fairly trivial piece that recalls Douglas Adams more than Bradbury. Robert McCammon’s post-apocalyptic “Children of the Bedtime Machine,” about an old woman who discovers a magical device in a diminished future, alludes to the desolate landscapes of stories like “The Wind” or “The Scythe,” as well as to the house in “There Will Come Soft Rains.”

Many of the contributors, of course, make little or no effort to allude to actual Bradbury works even indirectly. The editors tell us in their introduction that the stories are “neither sequels nor pastiches” — a wise decision — but John Maclay reveals in his afterword to “Max” (a tale more redolent of Ellison than Bradbury) that the invitees were asked to submit something “Bradburyesque” or “Bradbury-informed,” the latter category seeming to provide a huge amount of leeway. So some contributors, such as editor Weller in “The Girl in the Funeral Parlor” or Audrey Niffenegger in the fairly slight “Backwards in Seville,” draw on their own rather melancholy memories of actual events (I know I’m taking advantage of the afterwords here, but they’re a central part of the anthology), while David Morrell offers a skillful but unexceptional ghost story in “The Companions” and Ramsey Campbell a ghost story of a different sort — perhaps echoing Bradbury’s conceit that the survival of even one copy of a book somehow keeps the author alive — in “The Page.” Jacquelyn Mitchard’s “Two of a Kind” is an involved tale of a family business and the memory of a childhood crime, while co-editor Mort Castle’s “Light” presents, in self-consciously attenuated form, incidents from the life of Marilyn Monroe. It may be, along with Bonansinga’s “Heavy,” one of the few pieces to recognize Bradbury’s long love affair with Hollywood, but is otherwise an anomaly.

What all this suggests, I suppose, is that even when Bradbury undertook to explore ideas, from the despoiling American culture of "The Martian Chronicles" to the awful warnings of “The Pedestrian” or "Fahrenheit 451," that’s not really what writers have taken away from his work. The language, yes, and the desolate landscapes, empty streets, and lonely figures, and certainly the celebrations of childhood friendships and libraries and the ends of summers (he’ll always own October) — but not much in the way of social or political thought. It may turn out that Bradbury, certainly among the most popular of American writers, was also among the most populist, someone who, like Edwin Arlington Robinson or Aaron Copland or Andrew Wyeth (whom Bradbury cheerfully proclaimed a kindred spirit in the one letter he ever wrote to me) presented technically brilliant celebrations of a certain kind of Americana, who did what they did as well as anyone but who — after a certain point — chose to do no more. Bradbury may have done as much as anyone to shift the rhetorical mode of SF from synecdoche to metaphor, to teach generations of later writers (including the ones in this book) that worlds are made as much of language as of imagination, to carve out such a distinctive space that “Bradburyesque” has become as instantly recognizable a descriptor as “Kafkaesque” — but at some point, which I’ve (admittedly arbitrarily) suggested was around 1962, his focus seemed to shift from becoming Ray Bradbury (to borrow again the title of Jonathan Eller’s book) to being Ray Bradbury. The stories in the later collections — "Quicker Than the Eye," "The Cat’s Pajamas," "One More for the Road" — are not mentioned at all by the contributors to "Shadow Show," nor are the late novels in which Bradbury revisited his earlier iconic worlds, such as "From the Dust Returned" or "Farewell, Summer," though there are moments of brilliance in all of these. But these books didn’t add to the legend so much as allude to it, and they aren’t the ones through which young readers will be discovering Bradbury for a century to come. But the fact that they will be discovering Bradbury, or that Bradbury could have helped shape such diverse and accomplished talents as those represented here, should be monument enough.

More Los Angeles Review of Books

-

Sphere Theory

A Case For Connectedness -

Flesh World

The new uncanny

N/A

Shares