I spent one of my first nights in Nanjing with a Chinese girl with blonde-streaked cropped hair, who sported fishnet stockings, a short skirt, and a thorny red rose tattoo that snaked up her leg. She swore like a truck driver and went by the moniker Ruan Ruan; she wouldn’t tell me her real name. All throughout the summer of 2010, girls in the bar would stare at her and whisper her name; she was a citywide celebrity as the front woman of a Chinese punk band called Overdose. Their latest album, Die With Me, had taken its name from the title track, in which she wails about a girl getting an abortion.

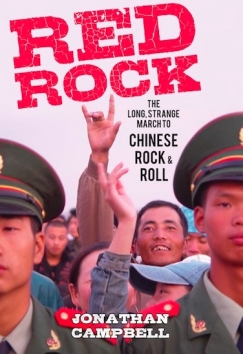

Jonathan Campell’s Red Rock tries to unravel the mystery of seemingly impossible scenes like this one taking place in a country where, just a few decades ago, the vaguest hints of Western sympathies could make you politically suspect, even land you on the wrong side of a virulent political campaign. As Campbell aptly puts it, while every aspect of Chinese life has seen rapid development, rock music in particular has charged ahead to the point where if one looks too far back at its history, one ends up “staring at an empty patch of land.”

Still, Chinese rock music, or yaogun, remains under close government surveillance; touring Western acts are no exception. The Bjork Incident, as Campbell glibly names it, was just one small event in the history of the country’s relationship with rock. The book criticizes the various talking heads that have only skimmed the surface of what Chinese rock means, which Campbell, as an outsider on the inside (he spent a long stretch in Beijing, booking acts), feels compelled to illuminate.

His journalism is not that of “the enemy,” a distinction that becomes the crux of another kind of love letter to rock music, Almost Famous. It’s hard to resist the empowering narrative arc of the last 20 years of Chinese rock, and Campbell finds few faults in the music, only in “The Man,” as he refers to the Chinese government and Communist party. Campbell settles somewhere between expert and groupie (he describes yaogunners as being “drop kicked […] across time and space.”) His personal website hosts his own timelines from the 20th century; cutout photos of Chinese rockers, alongside parallel Western timelines that read, “Meanwhile…” have a zine-like, DIY quality.

Campbell views his subjects from a distance; there are no character studies or exploration of the personal question of why yaogunners did what they did. He catalogs nearly every major musician of each era like a true enthusiast, or a fan who can’t decide on which posters to hang up. While the accounts in the book about the birth of American rock build steadily toward the cataclysmic 60s, in China, it goes from zero to 60 — or it may just be indicative of the country’s rapid development in most sectors. Though the two-decade-long time frame seems like the right amount for this book, really, there is probably material for three volumes. Characters and songs whiz by with barely enough time to realize them fully. Even the monumental Cui Jian, a hero to many of participants in what Chinese tend to call the “June 4th Movement” (in honor of the date of the massacre that ended that 1989 struggle) seems elusive and sketchy, weaving in and out of the narrative much like the name Kurt Cobain traveled through China in the 90s.

But this kind of fandom seems seldom granted to American rock now, music drenched in irony and loved by the people who cling to it (would Americans take an Occupy Wall Street protest song seriously?). There’s something refreshing about Campbell’s idolization of rock stars as promoters of true social change and not just people who put their influence behind it. The book is about China, but inseparable from the author’s identity as a Westerner who chose to live there, not here. There’s no small hint dropped that China’s 1980s music scene bore a strong resemblance to America in the 1960s. Wang Shuo is famously quoted as saying, “What didn’t happen through June 4 will happen through rock.” Campbell has written the kind of book American teenagers, for whom the era of rock and rebellion has long passed, will relish.

It’s music to be less jaded about, and Campbell produces examples of the ambivalence of Western rockers to great effect. While Chinese musicians faced their own problems with censorship at home, so did bands tapping the new market find the very real artistic limitations in China hard to comprehend. At one point, Pet Shop Boys’ Neil Tennant asks, “Does the Chinese government really fear the power of a song to bring about social change?” The author answers for him, “One might reply, ‘Doesn’t the lyricist believe it?’” “Red Rock” is a portrait of music made in earnest — even the name yaogun itself clings faithfully to its English equivalent (the word literally translates as ‘shake-turn’ or ‘rock-roll’)—and Chinese rockers will see no shortage of “The Man’s” very real presence any time soon.

Then again, that poses a paradox inherent in Chinese rock, addressed in the final chapter: as long as bands stay under the radar, the government cares little about what they say.

“The Party’s message: don’t challenge us politically and you can pretty much do whatever you like,” Campbell puts it bluntly. “As long as your grey-area/illegal activities aren’t up in our face and, more importantly, the line in the sand remains uncrossed, we’re all good.” To gain a share of the national (or international) spotlight has become synonymous with selling out, for “if one could be lifted from the pseudo-underground status of yaogun up to a height worthy of Famous, little would distinguish one from the latest traditional popstar.” In this way, fame is repulsive to true Chinese rockers: one even says that he tries to limit his TV appearances.

In Nanjing, I remember Ruan Ruan did some touring, but remained mostly anonymous outside her city. By now, Overdose has broken up. Her celebrity, like the perpetually underground status of many yaogunners, lives in smoky, windowless bars where people may or may not still talk about her. The price of rock is staying almost famous.