In the wake of last month's New York Times dispatch about reporters letting powerful politicians edit quotes before publication, various establishment media outlets angrily denounced the practice. Seeking to distance themselves from the ugly image of journalists serving as de facto spokespeople for the politicians they are supposed to be scrutinizing, these outlets made such a public spectacle in order to reassure their audiences that they would never trade ethics for access.

But, of course, anyone working in journalism in recent years knows such trades have long been standard practice. Today's reporters are expected to acquiesce to demands by politicians, and most often, they do just that. And while their feigned public umbrage at the Times' quote approval story shows that news outlets are at least smart enough to be embarrassed by their unscrupulous behavior, it doesn't mean the behavior has stopped. On the contrary, as last week's headline-grabbing interchange between a local Colorado reporter and the Romney campaign shows, that behavior persists, with the establishment media serving as a proud enabler.

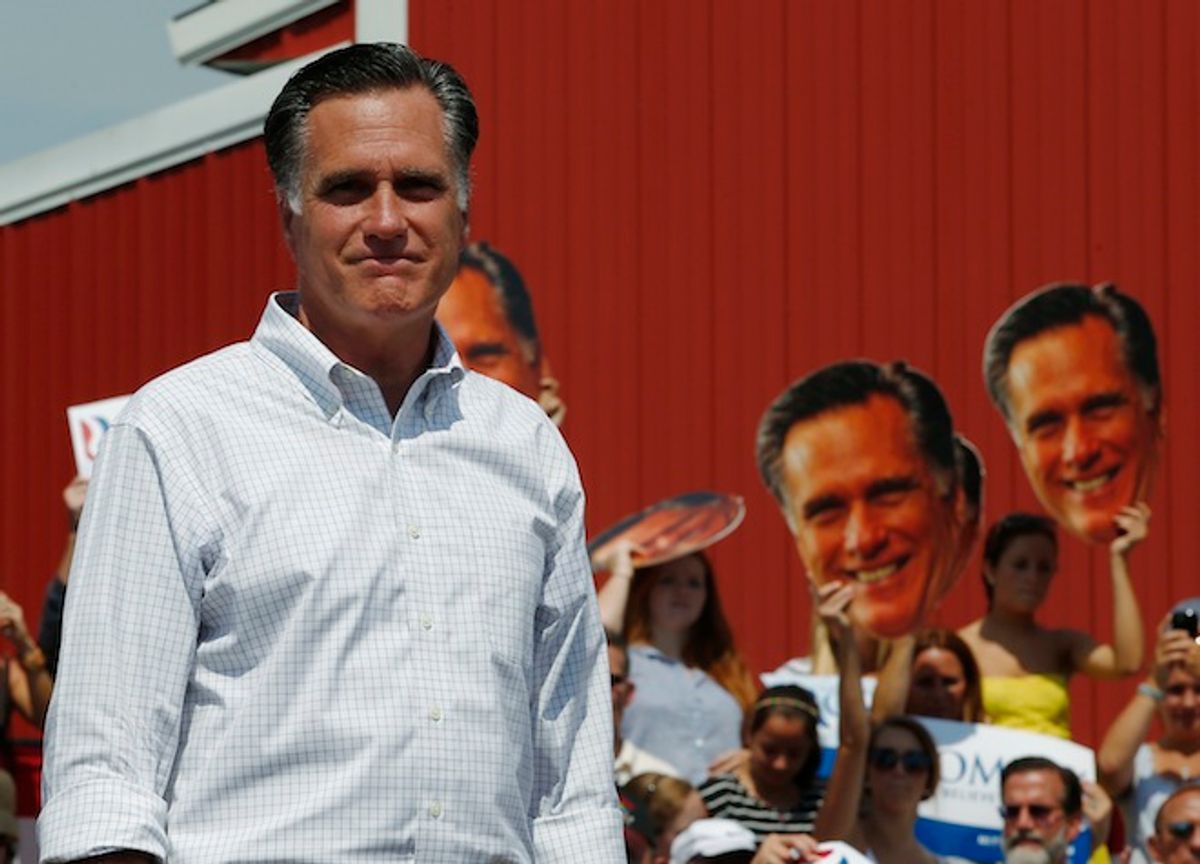

Here's what happened: According to CBS 4's Shaun Boyd, she was asked by Mitt Romney's campaign to do a satellite interview with the Republican presidential nominee, who wanted to get a carefully scripted message out to this swing state's voters. Boyd agreed to do the interview -- not surprising, because it could be (and was) billed as a major scoop for her local news station. This was no ordinary Q&A, though. Fearing a repeat of Boyd's laudably hard-hitting interview of Romney back in May, Romney's campaign demanded that Boyd not ask the candidate about abortion or the Todd "Legitimate Rape" Akin controversy. Incredibly, Boyd agreed.

When the interview occurred, Boyd (unfortunately) held up her end of the sordid deal, not asking Romney about what has become one of the defining issues of the entire election. However, she did tell viewers about the no-abortion-question condition, which consequently became a story unto itself.

Democrats and news organizations pounced on Romney's interview conditions, correctly citing them as proof that he doesn't want to answer tough questions. Meanwhile, Boyd basked in the reflected glow, garnering national and local media attention that portrayed her as a supposed star fighting the good fight on behalf of journalistic integrity. For instance, the Washington Post featured her in a "wide-ranging interview" and touted her for giving "serious consideration to the handling of the staffer’s extreme conditions" (and yet then submitting to them). Likewise, in the local media market, Denver Post editorial page editor Curtis Hubbard gushed on Twitter about Boyd, while the Post's Alicia Caldwell took to the paper's website to congratulate Boyd for "push(ing) back against the Romney camp's conditions."

Amid the celebration, though, these same voices of supposed journalistic integrity forgot to mention that Boyd didn't simply reject Romney's interview request and then do a story about the demands -- a move that would have been genuinely praiseworthy. Instead, she publicly complained about the conditions, but nonetheless acquiesced to them. Sure, she was absolutely correct to acknowledge the conditions on the air before airing the Romney-censored interview -- and, certainly, she should be given some modicum of credit for disclosure. But that disclosure shouldn't be portrayed as some hugely courageous act. On the contrary, being honest with viewers and disclosing such conditions is the absolute least any reporter should do when acceding to such preposterous demands. Indeed, the fact that Boyd's disclosure was so venerated implies that it is now all but unheard of in newsrooms to even respect that minimum standard of transparency.

What's so especially damning about this episode is that Boyd likely had leverage in this situation. After all, as she said, Romney's campaign came to her asking for an interview, not the other way around. Put another way, Romney's campaign wanted something from CBS 4, giving CBS 4 more power to dictate the terms. Boyd or her bosses could have made the "beggars can't be choosers" argument, telling Romney he could have the valuable airtime he desired, but not with such preposterous conditions -- and if he didn't like it, they could have told him no deal. Instead, for the sake of access, Boyd folded, conducting the interview on Romney's terms and promoting it on CBS 4's website. Just as troubling, she was subsequently portrayed as a great hero by the same establishment media that publicly pretends to be offended by trading ethics for access.

This is the kind of thing that is no doubt happening every day on the campaign trail -- and it has profound long-term effects. As KDVR Fox 31's chief political correspondent Eli Stokols told me on Friday, whether it is a reporter like Boyd accepting such conditions or other media outlets condoning such compromises, campaign reporting is now actively -- and knowingly -- contributing to the degradation of both journalism and America's democratic process. He said:

"We in the media all see how campaigns try hard to limit information, restrict access and force their limited engagements with the press to take place on their own terms. It's depressing that elections, at least from the campaign side, are no longer about getting information to voters so they can make informed decisions, only about getting voters to make the decision the campaigns want them to make. But when we accept a campaign's terms of certain questions being off limits or allowing staffers approval on quotes, we are both accepting and enabling the smallness of our politics; and we're diminishing ourselves and our profession in the process.

"It's a sad state of affairs when journalists are so desperate for anything resembling a scoop that they willingly acquiesce to ridiculous stipulations and conditions because scrubbed quotes and contrived interviews still make us feel good as long as we can call it 'an exclusive'."

While voters may not know exactly how the reporter-politician relationship works, their vague sense of what Stokols describes is almost certainly one of the reasons they have lost faith in the press corps. Until more rank-and-file reporters, editors and news producers renegotiate the terms of those relationships on more ethical grounds, that faith will continue to diminish -- as it should.

Shares