Here’s what you should know about Molly Ringwald. 1. Despite whatever you think you know about her — there’s more. 2. She is exactly how you imagine her to be; smart, funny, self-aware. 3. She has a lot more experience living with what it’s like to be Molly Ringwald than you ever will.

She’s got special powers, and by that I mean she’s truly exceptional — if you spend a couple of hours with her, you’ll want her as your best friend. And in the future when things happen — and they will — you’ll think, Molly would really get this. Molly would know how absurd and cool it is all at the same time. And you’d be right.

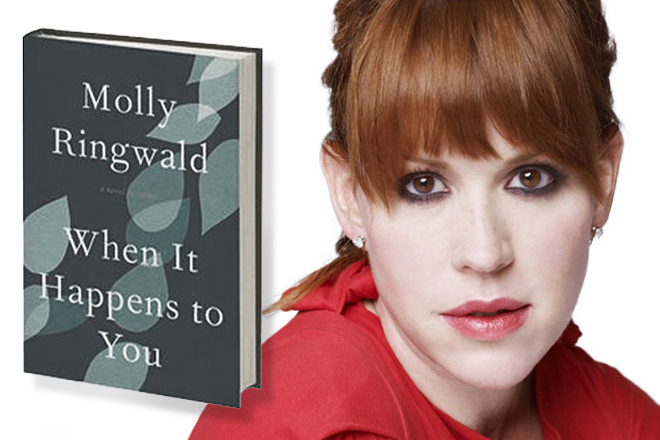

I met Molly Ringwald for lunch in Los Angeles to talk about her new book, “When It Happens to You: A Novel in Stories,” and found her to be all of the above and more. She’s intense, thoughtful, incredibly well-read and serious about her work as a fiction writer. Her stories deftly capture the confusion and heartbreak of betrayal, the power of family secrets, and the struggle to find and maintain both autonomy and intimacy within a marriage.

I was especially impressed with her storytelling style — the stories echo a bit of Raymond Carver, Amy Hempel and Lorrie Moore. Ringwald also pulls off a very cool technical feat — the stories progress in the spaces between stories — there is an invisible gathering of momentum and you feel things are happening even when no one is watching. With this auspicious fiction debut you might actually forget Ringwald is also a film icon.

I was curious about how you decided to do your book as stories rather than as a novel. I thought it has an interesting flow because it carries if not a literal ellipses, there’s a space between the stories where more happens. It’s like modernist architecture, like you drew it as a building.

Well, I think the structure kind of happened a little bit … I won’t say by accident, but I knew what my subject matter was. I wanted to write about betrayal in as many ways as I could understand it. I mean there’s so many different kinds of betrayal. Obviously the first story is about marital betrayal, and then the third story is really about a betrayal from her mother to her son.

If you think about things that have connected us, betrayal is one of them. There isn’t one person who hasn’t betrayed someone or been betrayed themselves. If there’s someone who said they hadn’t been on one side or the other, they would be lying. Once you’re our age and you have kids and you see mothers at school, you can see one marriage failing after the other. That sort of happened to me, where three or four of the women I had bonded with — they’re all divorced now. And in their cases, all of them, it was because of a betrayal. That’s why I wanted to write about it. Originally I had intended for the stories to be much shorter and the net was going to be much larger. The book really started to take form when I wrote an 11,000-word story and tossed it.

What was that story?

It was a different character. It was a different couple altogether, and I was toying with the women meeting because I always knew I wanted there to be a connection between the stories. That’s always something I’ve sort of liked, for some reason. I like that it has a sort of a scavenger-hunt quality to it. Then I realized it didn’t belong in the collection, and it was at that moment that I really started to narrow the lens and focus on the cast of characters that I had.

What I really love about the title story is that it reads like an incantation. It’s really astounding in its rhythmic quality and it’s clarity.

Thank you, wow. I was really proud of that story, just because I knew that I wanted to write something that was kind of like as deep in Greta’s psyche as possible to expose this agony of what this kind of betrayal is. I kept thinking about the Talking Heads song – “And you may ask yourself” — and it was the same sort of feeling.

I was surprised that Greta did open the possibility of getting back together with Phillip because you’re capturing a betrayal, and she’s so incredibly wounded and caught off-guard. Obviously she knows the young woman the affair happens with, which was excruciating. But in therapy, he’s also confessing how far it goes, and you totally know what he’s done before she does, and afterwards you realize it’s entirely in his character.

It’s pathological.

Right.

He’s been that way for a very long time.

It’s interesting. And the way you’ve toned the stories, they don’t shift locality, but each one is approached in a slightly different position, so it’s cool. You actually sort of learn something different about them.

I’m going to tell you, it’s so thrilling to hear you talking about my book. I don’t know if you ever get over that as a writer, but for me…

I actually can’t bear it.

Really?

Because I’m such a spaz.

It probably comes from my career as an actress, which is a call and response that you don’t have as a writer. The only person who read the stories when I wrote them was my husband, Panio, and that was it, which was really heavy for him. But I was like, “For God’s sake, now is not the time to tell me I look good in a pair of jeans I don’t look good in! If it sucks, please tell me.” And he was great. He was always there to tell me, “You need to go on more, you haven’t said enough,” or “OK, something needs to happen right now.”

I’m curious about the endings to each story because they’re so specific and so finely tuned. How did you know when you were pleased with a story? Did those endings come easily or did you have to do a lot of revising?

I think most of them came pretty easily. “My Olivia” (a story about a woman struggling with her young son’s desire to be a girl) was interesting because that didn’t end the way I thought it would. I had this image in my head, almost cinematic, and it had to do with Olivia walking to school, and I could see her/his hair and everyone’s reaction. I had sort of been toying with this vision for the longest time, and then when I was in the scene where she’s in the place where she buys the dress (for Oliver) and says “This is for my daughter,” it was like that was it. All of a sudden, bam, it just ended. My character ended my story. I read Ann Patchett’s book about writing where she says your characters don’t tell you, you are the one that controls them. But that character told me.

Ann and I, we were friends; we were in undergraduate and graduate together. I think for Ann it might really be like that.

I read almost every book about writing possible, and I find them sometimes helpful and sometimes not, and I liked her book. I just feel for me, it’s not the case because that character totally informed that ending. I think once you say “it’s for my daughter …”

There’s nothing else to say.

There’s nothing else to say. That’s it. And it’s funny because when Bret Easton Ellis wrote me an email after he read it and he was complimentary — as complimentary as Bret can be — he said he kept thinking about that story and it kept gnawing at him, and he kept wondering if she should have said “it’s for my son” instead of “my daughter.” And I don’t understand that.

I don’t know …

It makes no sense for me. If she were to say “It’s for my son,” she would have been being provocative with the sales lady …

Also, though she’s buying the dress, she still isn’t acknowledging him for how he sees himself.

She’s ready to take that step and say, “That’s my daughter,” which is a huge deal, you know, to say that as a parent — “That’s my daughter,” when biologically it’s your son, and to go to school and stand by that I think is the bravest thing you can do. I think that she’s the bravest character in the whole collection.

So I was curious: You watched this happen with two different parents who had children who wanted to be the other gender? I was curious how that, for you, became a story. I always think when I’m writing stories, I’m writing to get inside something or to understand something, you know what I mean?

In my experience there were two children, and one of them is without a doubt, he’s transgendered; it will happen for him. The second, he came to school, he had the crayons on the lips. My daughter that year was 5 and she wanted to have just an all-girls birthday party, so I decided to do this very girly birthday party, which is funny because she’s not girly at all now, but at the time she was. I decided to have a mani-pedi party, so we invited a bunch of her friends, and one of the people who she really, really liked at this school at the time was this boy. I wanted to invite him, but he was literally going to be the only boy, so I thought, “Well, maybe I’ll contact the mother first and find out what her feelings are about that.” I told her what the details were and she said, “Well, thank you very much for letting me know, we’re going to pass on this, um, you know, I’m aware of the situation and we’re working on it.”

Meaning they were working on it and they wanted to straighten it out?

Yes. So that was her point of view; I don’t know where he’s at right now. This story is his life four years on. I’m very curious to know what happened, but I don’t know. Then the other boy was … one symptom of a homosexual man is wanting to dress up as another gender, but it doesn’t necessarily become transgenderism, so this boy I’m not sure about, he could go either way. But his mom is like, much more like Marina is in the beginning where she’s just like totally accepting of it, sort of challenges whoever raises an eyebrow, and she’s really smart … (she says ) “this is what we’re going to do,” even though it’s scary to her. So I kind of just use both of those models in terms of one person. She’s one way, and then when she decides she’s going to strip everything out of his life she sort of becomes this other … I don’t know what I would do, honestly.

“The Little One” is the story about the older woman and Charlotte. It reminded me in some ways of Raymond Carver, but also a little sense of Shirley Jackson — because here’s Charlotte, this little girl who you always thought well of, who has this exchange with this woman that essentially seems to kill her.

That’s terrible.

You know what I mean? The power of the little girl over the older woman.

No, she is cruel, and I was thinking about it the other day and I thought, you know I can’t stand when I read things about children and they’re just absolutely adorable. I mean, Charlotte is adorable, and she’s bright and all that stuff…

But they can also say horrible things. My child can say horrible things.

I mean, in the first story when she reaches up and she takes Theresa and she kisses her on the breast — which has never happened to me by the way, but it could, because kids are cruel. It also resonated off the greater theme of the collection, which is that we are most cruel to the people we love the most. I think Phillip deeply loves Greta, but he is brutal. He is absolutely brutal to her. And I think that Charlotte loves Betty. She makes this connection. She does everything out of a sort of jealousy, so almost like a lover, but she’s brutal. She’s cruel. But she doesn’t really kill her.

Did you ever actually shy away from writing, for fear of exposing somebody or exposing something about how you saw or experienced a moment in your life as you were doing these?

I didn’t really, no. Because it is all fiction, you know. I wrote a nonfiction book before this that was very light, and it was the antithesis of this book in some ways, and I found that book actually harder to write because I was writing about myself, whereas this book I was writing under the guise of these characters, and I found that it was much easier and much more natural for me. Because I feel like if something is fiction — I feel the same way when I act. I can scream, I can look ugly, I can do whatever I want and it’s a character, so it’s fine.

But it’s really inspiring for me as a writer, somebody as brave as you, or somebody like Bret (Easton Ellis). I wrote to Bret when I was on my way to my parents’, and I was debating whether I was going to give or not give the galley to my mother.

(laughs) I’m just laughing because I’ve been there.

I was really struggling with it! I mean, I’m very close to my parents, both of them. And the funny thing is I use my mom a lot as a muse. I used her in my first book, I used her in my second book, and I never write about my dad, which he’s sort of vaguely insulted by. But there’s certain parts of Elsa that are like my mother, not everything, but you know…

Yes, I do know.

And there are certain parts of Betty that are like her too. But I was really stressing. My mom is like … We always say that she could be Amish, like if she could be Amish she would be, like if children could just be born by divine conception, I think that would be just fine with her. So the idea of handing her this book where there’s a masturbation sequence, and …

There’s sex, and …

I think I write about pubic hair, and just the idea that my mom …

Yes, even that your mother would know you know that word.

Yes! (laughing) Oh my God! And I wrote to Bret about it, really stressing, and he wrote back this very harsh thing where he said, “If you give a shit about what other people think then you have no business writing prose.” It was kind of like a slap in the face; it was kind of like someone taking a glass of cold water … and when I first read it, Panio was driving, and I was like, “Fuck him! Can you believe he wrote that? What an asshole!” And then I thought about it, and it was like after I got over that initial reaction I wanted to print it out and frame it and put in on my desk, because how do you write prose if you care about what anybody thinks? You can’t, because everybody is going to find themselves or not find themselves in your characters.

Everybody is going to think something. That’s the bottom line, is that everyone is going to think something, whether it’s true or not. So what did your mom say?

She loved it. I couldn’t believe it. I could not believe it.

Did she see the parts that echo who she is?

You know, she said it was so fascinating for her because she said, “You know, I recognized all of this stuff from all of the years that I’ve known you from the time you were a little girl until now.” But she said it all went through this sort of filter where none of it really was what it really was — so she kind of understood the process of fiction, which is, like, more than I could ask for from one’s parent. And my dad, too. When I was up there visiting I read him “The Little One,” and you know my parents are just … they’re pretty great. They really are. They’ve always supported my writing. From the time I was little my mom kept saying, “This is what you’re going to do.”

How is the writing process similar or different than acting when you are sort of trying to kind of get inside a character?

Well, to me it’s very similar to acting — but there is this other step, you know?

You have to write.

You have to write, and then there’s prose, too, which is no small thing. I’ve done character biographies for years, and no one every sees that, thank God, because …

I didn’t know there even was such a thing.

I don’t know if every actor does that, but for me it’s always been part of the process, what does this person think about, what do they dream about, what do they draw about, what are their aspirations? In “The Breakfast Club,” for instance, I had a whole character biography going for that character, and once in a while it comes out, like there’s a line where I say I wish I was in Paris, and that wasn’t in the script. It was improvised. So that was just something I had always done all along, and I found that very helpful. And also my ear for dialogue and also I think my ear for music, because I’m a singer, also, I think that all helps me. And there’s just the brick and mortar of writing prose.

Did you ever take writing courses, or did you just start doing it and keep doing it? And fortunately married a writer/editor? I gotta do that …

I would love to have an MFA program. There was a moment in time when … do you know a writer named Sigrid Nunez? I love her, I’ve always loved her, but I actually sought her out after her first book and met with her, and then there was a brief moment in time when I thought of going to Yaddo. But then I got a job, and I’m such a work horse that I just did that, and it actually took me a long time. It took a long time for me to give myself permission to write.

Can you talk a little about that?

I feel like it’s really the same for any writer. If you’re not getting paid — if you’re not under contract, it doesn’t feel real, or like you’re not worthy, or you’re not a real writer. And then it becomes a question of does art exist for art’s sake, or do you need to have a paycheck? Do you need somebody to call you a writer in print to be a writer? In my case it was I’m an actress, and the idea of an actress writing is like … how many actresses do you know that write?

Ethan Hawke.

OK.

Which is interesting.

There’s not that many, though.

There’s not that many.

And he’s not an actress.

Actors are way more vain (laughing). But there aren’t that many, you know …

There’s Ethan Hawke, there’s James Franco, Ally Sheedy wrote a children’s book … there’s not that many. Julie Andrews.

Julie Andrews, who writes great children’s books.

Jamie Lee Curtis. But yes, anyway, but also, you know, your stories, they’re literary stories. Do you feel validated now? Do you feel like you’re allowed to say that you’re writing or that you’re a writer?

Oh yeah. Totally.

You’re like, “Oh yeah!”

Fuck, yeah! Fuck, yeah would be the appropriate response to that. You know, it’s weird I used to feel when I was acting, when I first started when I was kid, that I was exactly where I wanted to be or needed to be. It was like all the planets aligned, and I was just in a groove and I was where I needed to be, and it was hard to focus at school. I had already discovered acting and that’s where I wanted to be. And over the years, that’s shifted to where I get that feeling when I’m writing, or more precisely after having written because I don’t actually very much enjoy the process of writing. It’s hard. And it’s solitary, but once you have kids there’s sort of a pleasure in kind of having that time, if you can get the time.

So thinking a little bit about the actor in you. How do you go from sort of that enormous early success; how do you live a normal life? And how do you then, ultimately, become a regular person and a regular working actress? Was there a transition? How do you reconcile those? Because obviously it’s an odd thing.

I don’t think I’m ever going to have a normal life, really, is the honest answer. I moved to Paris in my early 20s, and even though at the time I didn’t think that I was running away from anything or escaping anything, looking back on it, it seems to have made sense, you know? I’ve always been somebody who isn’t terribly comfortable with that kind of celebrity, and I never have been. I looked at my sister — I have an older sister who’s always loved everything having to do with Hollywood, and my 8-year-old daughter, who I take her to the premiere of “Brave” or whatever and once she gets to the red carpet she wants to go back and do it all over again. And I’ve never been that person. Even when I was little that was never what was interesting to me. It was always the work and the character work. It was really kind of more the writing aspect of it, you know? I never expected for those movies to become what they became. I knew they were good, and I knew they were interesting and I enjoyed making them; I never, ever expected them to become …

Entirely iconic and of the …

Yeah, and I think they definitely affected my, you know, career. But the choices I made in my life to go to Paris and learn French and work with Jean-Luc Godard and Cindy Sherman in New York I think made me a more interesting person and ultimately a more interesting writer.

Did you ever write screenplays? Did you ever think that was something you wanted to do?

Yeah, and there’s a few that I worked on that I never really … just like there’s short stories that I’ve worked on that I never felt like kind of came up to the level of excellence. I’m not saying my book is excellent, but you know what I mean.

It didn’t qualify.

I felt, no, I’m not there yet. And I never really felt that way with the screenplays, although actually I’m thinking about adapting this book for the screen, and I’d like to direct it.

I was just going to ask you would you ever direct something.

Yeah, I’d like to direct it, and if I play any part in it I’d probably play Marina, the redhead. I don’t see myself as Greta at all, and I already have somebody who wants to play Peter. Do you know Demetri Martin?

No.

Oh, he’s great. He’s a writer, he’s a comedian but he’s also a writer; Grand Central publishes him, but he’s also an artist so he’s kind of like, perfect. So I gave it to him and he was totally on board, and I would like him to act in it and to animate it as well. I’ve been thinking about, you know, of course this is just a wish list, but Sarah Polley as Greta. She’s a little bit young, but I figure by the time it actually gets made she might be close to the right age.

Back to the book: Did you write these stories in order?

Well, they were written in a linear fashion until I was in the middle of writing the story about the actor, and I had the idea to write “The Little One,” and I couldn’t get it out of my head. I was writing this one story, and it was driving me crazy, and Panio was like, “just stop. Just write the story. Just write it, and you’ll come back to it; you already know what “Ursa Minor’s” going to be, so don’t worry about it. Just write “The Little One,” and it will come back to you.” That was the only time.

That was the only time that they were out of order. That’s interesting. It’s very cool; it’s not like in any way an overt space, like “Oh, she left something out, “but it’s almost like you drew away from it; there’s almost like a negative space. There’s like form left between one to the other. But it works.

Yeah, it felt very right to me, you know, musically. I’ve always loved Carver and Joan Didion and everybody who has managed to say so much… it’s the same thing you seen in actors, you know? James Gandolfini, you know, you watch him in “Sopranos” and everything that he says with his face — it’s like that. To me it is interesting. So I think I tried to get that across. If I had written every moment in order of Greta finding out and then Greta breaking down, if I’d written it in a totally linear fashion, it would have been a very boring book. I thought it would be more interesting to have the story reveal itself in that different time. I think. (laughing)

Your dad is a jazz musician, a pianist. So tell me what you listen to. Do you listen to jazz, or what do you feed on?

I listen to jazz a lot, but it’s kind of like my comfort food. But I listen to all kinds of things. I listen to alternative, and classical. Do you listen to music at all when you write?

I was just going to ask you that.

I do. I would put music in really, really low for each character because Betty was so into classical music; it was so much a part of her and who she was that I would just put Pandora on. Glenn Gould was like a huge deal with her and her husband, and it was sort of based on this person that I knew who lived in the ’60s who, you know, just knew nothing about the Rolling Stones but just lived in this little bubble. I feel like it helped me inform the characters.

And who did you put on for the others? Now I’m curious.

Remember, you can never put on anything too loud, because then it becomes too distracting and you can’t write. But when I was writing “Ursa Minor,” the Peter character was very alternative. He was listening to Bon Iver, or Andrew Bird, you know? Things like that. Then it became this sort of Chet Baker kind of party soundtrack. And so through the whole thing I kind of had these different soundtracks and then there were times when I didn’t listen to anything.

There’s things I can listen to, like “Suzanne,” a thousand times and I’m like, oh, sure!

Yeah! Well, if there’s something that you know fairly well, then…

It’s like a signal. Like Joni Mitchell, it’s just a signal to go right in there.

There’s certain times, I remember, on the Pandora I was writing and I would stop writing and start listening to the lyrics. I would be like, “what are they saying? What’s that lyric? That’s a weird mixed metaphor; why are you saying that?”

Do you know Rosanne Cash at all? Because Rosanne wrote a memoir, but she also wrote a book of short stories. She’s a really big reader and a really interesting writer.

Is she a good fiction writer?

It’s funny you said that, because I don’t know. I need to go back; I’ve been called out. Her memoir was incredible, actually.

Who are your favorite writers?

I have different ones. Really John Cheever, Richard Yates, a lot. They tend to be male writers. Joan Didion would be one of the few women. Grace Paley, who was my teacher.

She must have been an amazing professor to have.

She was, she was. She looked like Yoda and literally when she was my teacher I would go in there and I taught myself to just keep a very straight face. You would go in there and she’d be like, literally standing on the radiator. “Grace, why are you on the radiator?” And she would be like, “Oh, I’m trying to do something.” Or she would be rolling on the floor and you would be like, “Grace, why are you lying on the floor?” “Oh I hurt my back last night.”

I just taught myself to not let myself think, “Oh my God that is so weird.” She talked a lot about writing the truth according to the characters, not what was accurate to you, which is a big young writer thing. You know, you’re always writing about how you see it, and that always for me was the way I would check things, like is this accurate to this character?

Yeah. And that’s hard. I find it’s one of the hardest things to do when you write something and you don’t agree necessarily with the character but you know that it’s right for that character.

Did you ever meet Toni Morrison?

Only in passing.

I went through like a huge Toni Morrison phase in my 20s. I started with “Song of Solomon,” and I was sort of astounded by her writing. It was interesting because she’s one of those people you read and think, “I could never do that. I could never do what she does.” But I was very inspired by it, and I would read it almost like poetry. It would kind of wash over me and I would have a feeling but I wouldn’t necessarily understand it. And then I would go back again and deconstruct it, but I really feel like it opened up pathways in my brain. And then I met her at the Time magazine party in, I don’t know, I think it was also in the ’90s or something, and I said I really want to write fiction. I mean, I’d already been writing fiction, but I wanted to write more, and she said, “Come to my class at Princeton. Just come to my class and sit in my class.” It’s one of the biggest regrets I’ve ever had.

You never went.

Because I got a job. I was like, “I gotta work; I can’t,” but I should have done it. That was my one chance, you know?

You know there’s still things you can do, even though it would have been fascinating to see what she had to say.

Oh my God, it would have been amazing. She was so lovely, though. She was so… she didn’t like raise an eyebrow when I said I wanted to write fiction; she was very embracing of that. And I don’t think all writers are like that. Joan Didion is a great inspiration to me, but I’m not going to go knock on her door for writerly advice!

But it’s also just who she is … and like the warning sign of health says, don’t knock on my door.

My last story is based on something that she said.

Really?

Well, something that she allegedly said, which was “You have to pick the places you don’t walk away from.” So I named the last story “Places You Don’t Walk Away From.”

And where did she say that, or allegedly say that? Or where did you hear that she allegedly said it?

Online. I’m a total Internet junkie. I think I’d originally called it something else, and just that line wouldn’t leave me along, “You have to pick the places you don’t walk away from,” I sort of felt like, this is it. These are the places you don’t walk away from.