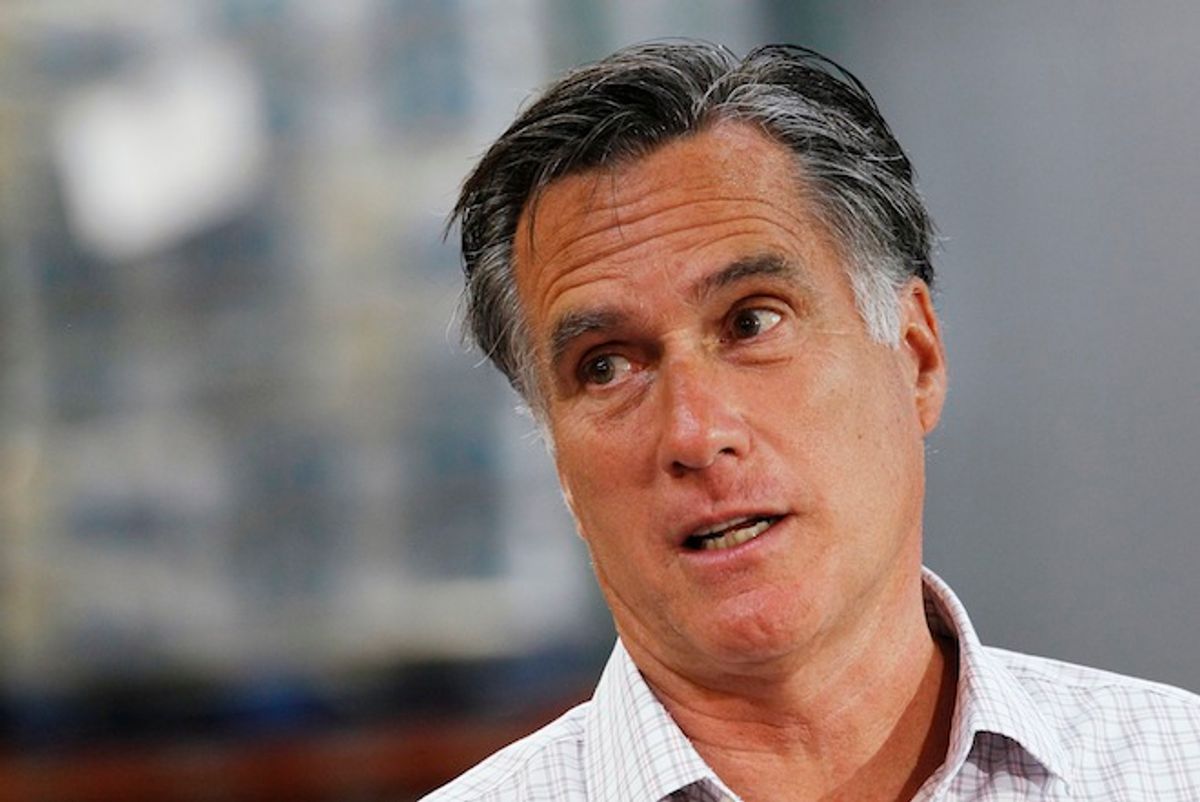

Josh Barro, writing from his new column at Bloomberg, wonders if Mitt Romney has a secret economic plan to fix housing: "But where I think a big improvement from Romney is likely is on housing policy. While Romney has been conspicuously silent on housing, one of his top advisers, Glenn Hubbard, advocates an aggressive plan to restructure mortgages. The Hubbard plan would lower mortgage rates and reduce principal for underwater borrowers, both of which would stimulate the economy. That's a tough sell to Republicans in Congress -- but they would be much more open to it under a Republican president than a Democratic one."

As David Dayen noted in a great, comprehensive Salon piece, none of this matters if Congress doesn't extend a special law put into place during the crisis that keeps principal reduction, even reduction from a short sale, from being treated as income, and thus requiring it to be taxed. The law is set to expire on Dec. 31, 2012. Extending it has bipartisan support in the Senate, but none in the House so far. I can't emphasize how much this matters — homeowners would get a giant tax bill under any relief program, making such programs difficult to do. It isn't clear what Romney would do about this.

It's worth noting that the Hubbard plan is very similar to the ongoing Home Affordable Refinance Program (HARP) in that it uses the GSEs to refinance underwater mortgages. HARP was revamped earlier this year to HARP 2.0, which removed a 125 percent loan-to-value limit and waived certain representations and warranties for lenders. It's still early, but it looks like there is a big increase in the number of underwater mortgages refinancing (FHFA data). Over 40 percent of the HARP refinances in July were from mortgages with an LTV over 125 percent. As will become relevant in this post, their proposal is GSE driven and avoids bankruptcy reform, as "moving mortgage debt into bankruptcy courts could well reduce future credit availability and hamper long-run economic growth and homeownership."

(The original Hubbard plan from 2008 featured mandatory principal writedowns for negative equity, with the losses shared equally by the lender and the government. In exchange, the government gets a lien on the home worth 20 percent of any increase in value. This is much different than current HARP policy and constitutes a really bold approach. However, this negative equity and shared appreciation part is entirely missing from the current 2011 version of the proposal. I'm not sure why Hubbard dropped that section; certainly it's not because the housing market has done better than expected.)

How can we analyze what potential solutions a Romney presidency could embrace? There's normally one dimension we think of in terms of housing crisis policy, and that is how aggressive we are in dealing with underwater debt and foreclosures. Should we refinance underwater mortgages to create lower monthly payments and take advantage of low interest rates? Should we go further and reduce principal debt, either outright or in exchange for some form of equity claim?

But there's another, equally important dimension, and that's the mechanism through which these policies are enacted. What is the vehicle that will be used to execute policy? There are four general cases that can be put into play.

The first policy mechanism tries to go through the financial sector and the mortgage servicing system as it currently exists. This takes the market as it is and tries to nudge agents to act a different way with various incentives. The Home Affordable Modification Program (HAMP) program does this by trying to nudge the industry with payments to make modifications that lower interest rates and payments. HAMP was consciously not designed to do principal reductions, though it does have a very small, limited program now.

There's a second policy vehicle driven by the fact that the GSEs are in conservatorship under the FHFA. The FHFA's mission is to "Provide effective supervision, regulation and housing mission oversight of Fannie Mae, Freddie Mac and the Federal Home Loan Banks to promote their safety and soundness, support housing finance and affordable housing, and support a stable and liquid mortgage market," which can support a variety of policy ideas. As mentioned above, HARP is responsible for refinancing GSE loans, and the Hubbard plan focuses on refinancing through the GSEs. Timothy Geithner's recent effort to get the FHFA to support principal reduction through a program called Home Affordable Modification Program Principal Reduction Alternative (HAMP PRA) was recently rejected by FHFA acting director Ed DeMarco. Several progressives responded by calling for DeMarco to be fired.

There's a third policy vehicle designed to change the basic legal framework for how bankruptcy works. Bankruptcy law could be modified, even temporarily, to deal with the consequences of the housing bust. The mass modification program (also see here at Slate) proposed by Eric Posner and Luigi Zingales, for instance, worked through bankruptcy law. The failed effort to pass a "cramdown" or lien-stripping amendment was entirely about letting judges write down mortgage debt in bankruptcy.

And then there's the fourth mechanism of direct government policy. Here the government actively goes out and purchases and manages mortgages. The New Deal created the Home Owners' Loan Corporation (HOLC) to directly purchase mortgages; we could recreate such a mechanism today. Both John McCain and Hillary Clinton argued for such programs during the 2008 campaign. Senator Merkley's recent plan would do this for refinancing; eminent domain proposals would do this for principal reduction.

Let's grid out those two dimensions:

With this grid in mind, let's re-examine the high-level critique of the Obama administration's housing policy. During the debate over the second round of TARP, the then-incoming Obama administration promised to take action on bankruptcy reform and hinted toward direct government action, or the top two rows in the grid. Larry Summers wrote to Harry Reid promising action on "reforming our bankruptcy laws." Donna Edwards wrote that she "appreciate[d] the personal commitment that Senator Obama" would look "at a program such as one that existed in the 1930s to 1950s to work directly with homeowners."

This did not happen. Timothy Geithner was against direct government action from the beginning, as this letter he wrote to Brad Miller shows. The administration was publicly silent and privately pushed against reforming bankruptcy. The administration also seemed asleep at the wheel when it came to pushing for big action through the GSEs, making no recess appointments and only updating HARP and pushing for principal writedowns this year.

Their main effort was to work through the already existing mortgage framework. This effort has largely been seen as a failure. This isn't surprising, as there are well-documented problems with our current mortgage servicing system. The same problems with Wall Street slicing and dicing mortgages that were present when the housing bubble was inflating are still there now that it has collapsed.

We often don't get second chances in life, but the Obama administration had a second chance at a serious reform of this broken system when news of the scandals surrounding financial fraud started breaking. Though there's still a taskforce out there somewhere, I think it is safe to say the administration wanted to remove these problems rather than take them on directly, which would have opened up a space to reform the current system. They succeeded. This only leaves working through the system.

Maybe your eyes roll when you read the term "neoliberal hegemony," but there's something to the idea that the Obama administration simply felt that the only legitimate way to try and deal with the foreclosure crisis was by nudging the incentives of various markets this or that way. The market is the ultimate, efficient arbiter of value, and policy should only seek to adjust some incentives here and there. Measures to intervene directly by the government, or measures to change the way property is regulated through bankruptcy, were ignored right away. Those actions require the government to act as a force in the marketplace directly, or to acknowledge that the economy is created through law and can be adjusted accordingly, both of which are taboo under neoliberal economic ideology.

Working within a system, no matter how aggressive your actions are, means you don't ultimately have to challenge that system. As Harper's wrote back in 2009, in a great essay on President Obama as Hoover, "The common thread running through all of Obama’s major proposals right now is that they are labyrinthine solutions designed mainly to avoid conflict." In a practical sense, for Romney to go bigger than Obama on housing would require either adjusting the bankruptcy code, running a government program that directly intervenes in the marketplace in a big way, or firing DeMarco. In the theoretical sense, it would likely require challenging the reigning paradigm in political economy as well as challenging the current financial system. Are these actions realistic for Romney?

Shares