The importance of women to Barack Obama’s reelection hopes is no secret. The president consistently trails Mitt Romney among male voters, but so far that deficit is more than wiped out by his strength with females – which explains why the Obama team is redoubling its efforts to turn women against Romney and the GOP brand.

The proximate reason for this is the behavior of Republicans, who have placed a new level of rhetorical and legislative importance on reproductive issues in the past few years.

The shock value of Todd Akin’s “legitimate rape” comment a week ago made it an instant national story, but the controversy also focused attention on the lack of a rape exception in the antiabortion platform language Republicans will ratify in Tampa this week. This came a few months after the congressional GOP picked a fight with Obama over the administration’s efforts to mandate contraception coverage, and after Gov. Bob McDonnell and his fellow Virginia Republicans were forced to abandon a plan to compel women to undergo a transvaginal ultrasound before having an abortion. (Instead, McDonnell signed a bill that mandates a non-invasive ultrasound.) There’s also been a proliferation of “personhood” amendments at the state level, along with numerous other Republican-led efforts to restrict abortion. All of this has allowed Democrats to accuse the GOP of pursuing a “war on women.”

To understand the roots of the gender politics of 2012, though, you need to go back more than three decades, to the summer of 1980.

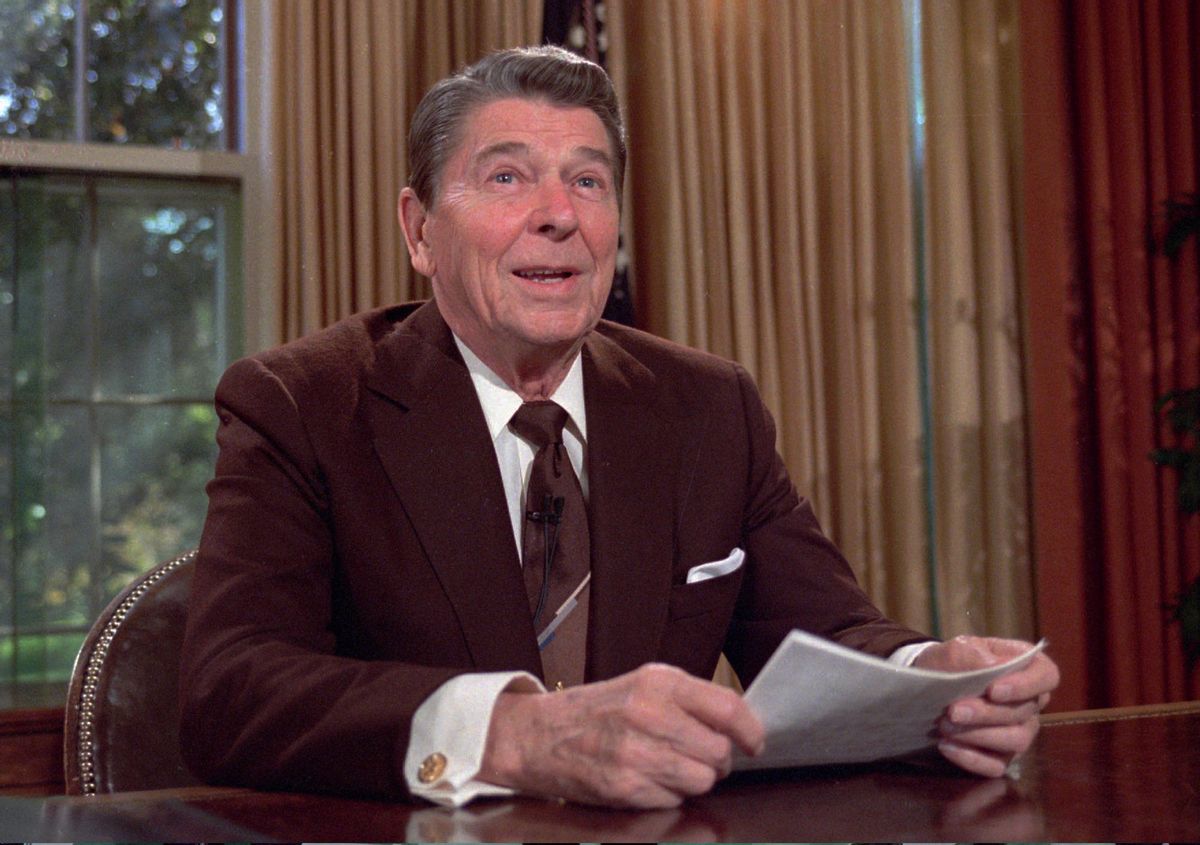

It can be hard to appreciate now, but the Republican Party that nominated Ronald Reagan in Detroit that July was far more diverse, demographically and ideologically, than today’s. In some ways, Reagan’s primary season victory cemented the rightward shift that Barry Goldwater’s 1964 nomination had begun, but the old Rockefeller wing wasn’t yet dead. Authentic liberals like Jacob Javits, Mac Mathias and Lowell Weicker remained prominent, and the party wasn’t intimately identified with Southern-tinged evangelical Christianity the way it now is.

Consequently, there was no gender gap to speak of in national politics – yet. In the previous presidential election, the Gerald Ford-Jimmy Carter contest of 1976, the same voting pattern had prevailed among men and women. Ford himself embodied what had been a long-standing tradition of Republican cultural moderation, embracing the Equal Rights Amendment – support for which had been part of the GOP’s platform for four decades – and arguing that abortion wasn’t a federal issue.

Reagan, though, had aligned himself with the social and religious conservatives who were increasingly prominent in the party. In the mid-1970s, as broad initial support from both parties pushed the ERA to the brink of ratification, Phyllis Schlafly led a right-wing uprising that stalled momentum and won over conservative leaders, Reagan included. Reagan was also cultivating an alliance with evangelical Christians, a long inactive voting bloc that had been energized by Carter, a born-again Christian, in 1976, only to become disillusioned during his presidency. As governor of California in the late 1960s, Reagan had actually signed a liberal abortion law, but by ’80 he ran as a staunch opponent of the Roe vs. Wade decision.

On both issues, he was at odds with his main GOP foe. George H.W. Bush, a former U.N. ambassador and CIA director, ran as an ERA proponent and espoused a Ford-like position on abortion. Nor was Bush alone among that year’s GOP field. Howard Baker, the Senate GOP leader who’d initially seemed like Reagan’s chief primary season obstacle, former Texas Gov. John Connally and Rep. John Anderson were also ERA backers. Baker had even supported public funding for abortion.

But it was Reagan’s convention, and the platform that was presented to delegates in Detroit included only a broad statement of support for gender equality. For the first time since 1940, it didn’t voice support for the ERA -- but it did condemn any effort by the federal government to goad states into ratifying it. And it endorsed a “human life amendment,” the first time the GOP had formally weighed in on the post-Roe abortion debate.

On the Sunday before the convention, the National Organization of Women – which had refused to endorse Carter’s reelection, citing the lack of progress on ERA ratification – staged a rally at a Detroit park to protest the platform. There were 3,000 attendees, some of them Republican delegates and officeholders.

“They say they are for equal rights, but not the amendment,” NOW’s president, Eleanor Smeal declared. “They are trying to trick the people. They want us to take 200 more years going statute by statute to improve all the affected by the ERA.”

To be sure, there were plenty of conservative women in the GOP who were delighted with the platform, but among moderates and liberals there was an uproar. In the middle of the convention, Reagan convened a meeting with female delegates, at which he promised not to make ERA opposition a litmus test for his running-mate pick and vowed to consider a woman for the Supreme Court. He also tried to coax Ford to join him on the ticket, and when that failed, he went with Bush. Even Reagan’s daughter Maureen expressed irritation with the platform, saying that “I don’t think equality is a debatable issue.”

Thus was the modern gender gap born. In a post-convention poll, 29 percent of women said the GOP’s ERA and abortion positions would make them less likely to back Reagan, compared to 14 percent who said they were more likely to support him. After bitterly opposing him in his Democratic primary fight with Ted Kennedy, NOW and other feminist groups reluctantly embraced Carter in the fall – only because they considered the Reagan-ized GOP an even worse option. The ’80 election is remembered as a landslide for Reagan, but almost all of it was attributable to men, who sided with him by an 18-point margin. Among women, Reagan barely edged out Carter, 47 to 46 percent.

To varying degrees, that gap has persisted ever since. Generally, Republicans have shown an awareness of the political downside of endorsing far-right views on reproductive and women’s issues. Their solution has been to etch those views into their platform while showcasing more moderate voices at their conventions – Tom Kean in 1988, Colin Powell in 1996, Arnold Schwarzenegger in 2004, Rudy Giuliani in 2008. (An exception came in 1992, when the party’s Houston gathering was defined by family values themes and Pat Buchanan’s “religious war” declaration.)

It’s tended to work, which explains why it was treated as such big news last week when the GOP’s platform committee endorsed a human life amendment. It was as if no one realized the party had done the same thing in the eight previous elections. Which gets to the problem for Republicans, and the opportunity for Democrats: Thanks to the antics of Todd Akin, Bob McDonnell and others, the press and the public are starting to look closely at something that’s been right in front of them for 32 years.

Shares