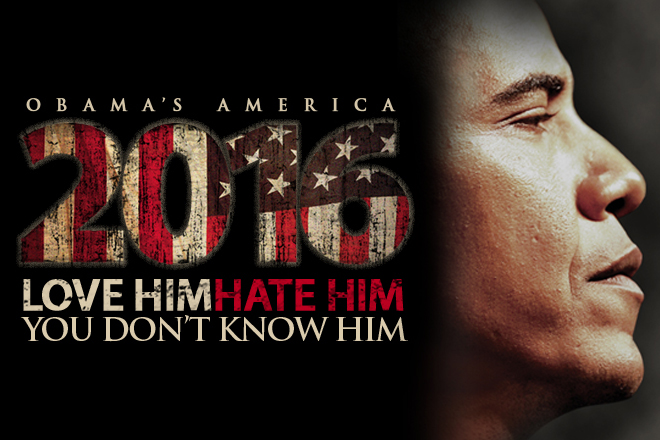

Surprising almost everyone, the eighth highest-grossing film this past weekend was Dinesh D’Souza’s “2016: Obama’s America,” a documentary in which the conservative author travels the world to find the sources of the president’s supposed anti-American, anti-capitalist radicalism. This was surprising for two reasons. One is that it beat out seemingly solid studio releases like “Premium Rush” and “The Apparition,” even though “Obama’s America” was only playing in around a thousand theaters (“The Bourne Legacy” is playing in three times that) and was in its seventh week of release. Many accounts compared it to the success Michael Moore saw with “Fahrenheit 9/11” in 2004.

That, however, leads us to the second reason for the surprise: Why would anyone pay to see a political documentary in 2012? Between 2004 and today, digital technology has forever changed the way we watch movies, and nowhere has this been more pronounced than in the realm of documentaries. The easy availability of video-editing software has led to an explosion of the form, and between BitTorrent, YouTube and sites hosting the videos themselves, access to them is easy and instant, a particular boon to a type of movie that is rarely commercially viable enough to command wide theatrical release. Thus, on the Web you can find videos criticizing everything from the Tea Party to the U.N.’s plans for world domination to the media’s treatment of suspected Aurora shooter James Holmes. Instead of hoping a semi-obscure documentary makes it to your local film festival, you can just go online, and as such the true interest in a documentary can be gauged in ways it never could before. Indeed, some have even become viral hits, like the 9/11 truther documentary “Loose Change.” Given that, why would you bother paying the 12 bucks and deal with parking at the local multiplex to go see the same basic piece of agitprop you could get for free in the comfort of your own home?

Stranger still is the fact that “Obama’s America” isn’t even the first right-wing movie this year to pull respectable box-office numbers. While not a documentary, “October Baby,” a religious drama about an “abortion survivor’s” search for her birth mother, did surprisingly well in wide release, opening at No. 8 despite only showing on 390 screens. Like “Obama’s America,” it pursued a strategy of rolling out slowly, showing at a handful of Southern theaters in 2011 before going broader the following year. Such a strategy swam against the current Hollywood wisdom that a giant opening weekend is the only way to success. But it’s allowed the films to more precisely target their audiences and build word-of-mouth. “October Baby” partnered with churches and organizations like Focus on the Family to organize group showings, then used those groups to pressure other theaters to show the film. As they put it in a press release, “grassroots groups in more than 70 communities pre-purchased enough tickets to bring the film to their local theaters.” “Obama’s America” was so successful in using this technique that before the weekend started, it was briefly the No. 1 movie in the country, due solely to the fact that more people had bought presale tickets for that film than any other. In an era where movies seem like the lone holdouts against the need to target niche audiences, films like these are finding a way to make it work by targeting one very specific niche: social conservatives.

That careful targeting is precisely why audiences are willing to come out and pay to see a movie not all that different from ones they can see for free at home. It’s the same logic behind Chick-fil-A Appreciation Day. When a group of people feel their values are under attack, they want to find some way to come out in public and visibly demonstrate their support. And so you go out and buy a chicken sandwich, or pay to see an anti-Obama movie, and it leaves a mark with a kind of legitimacy that YouTube views or blog comments just don’t have. More specifically, they become news events, and succeed in generating media coverage, which is what is supposedly missing in the first place. Boost the box office numbers enough, or create long enough lines outside a fast-food place, and the press will be enticed to write a story about the power of your political values, thus demonstrating to the other side that you will not be cowed. In an age when we’re told to buy certain kinds of coffee as a way of demonstrating our ideological commitments, it’s not surprising that these sorts of consumer actions are being seen, and used, as political speech.

Even more so, however, it makes sense that movie theaters have become the venues some choose to express their political strength. Film critics have long rhapsodized about the importance of seeing movies in a theater in order to get the true, collective experience of cinema. As Alexander Hulls put it recently:

Moviegoing is, at its core, a social experience. The moment those lights dim and the film reel rolls, you’re no longer an individual sitting in an auditorium; you’re part of a mass of people who are connected through a shared event and the desire to be entertained and transported.

That sounds a lot like a political rally, a form that, much like theatergoing, has declined in recent years. Commentators on both film and politics have lamented the fall-off in public attendance and its replacement by the private experience of watching a movie or a political speech at home, on a TV or computer screen. For all the pleasures those experiences can give, and for all that the Internet offers a perfectly valid and real form of social interaction, there is an undeniable hunger to find ways to have those in-person collective political experiences again without reverting to the now-discredited form of rallies and speeches. The left has done it with Occupy and its mix of collective decision-making, liminal space and protest. But the right, if these two movies are any indication, may be doing it through movie theaters, making the act of attendance into a kind of testimonial. In a single space, at a single time, we all get together to face the same way and listen to someone tell us what we already know about politics, not because we want the information, but because we want to see everyone else doing it, to have that civil experience, to feel less as if our politics are a strange, personal thing. It is a show of support, both for the cause and for the viewer. We do it not to do it, but to do it together, visibly and successfully and surprisingly.