When Gore Vidal died a few weeks ago, eulogies quoted his famous observation that “the more money an American accumulates the less interesting he himself becomes.” Vidal originally wrote these words in a 1972 essay on Howard Hughes, but who could read them today and not think of Willard Mitt Romney?

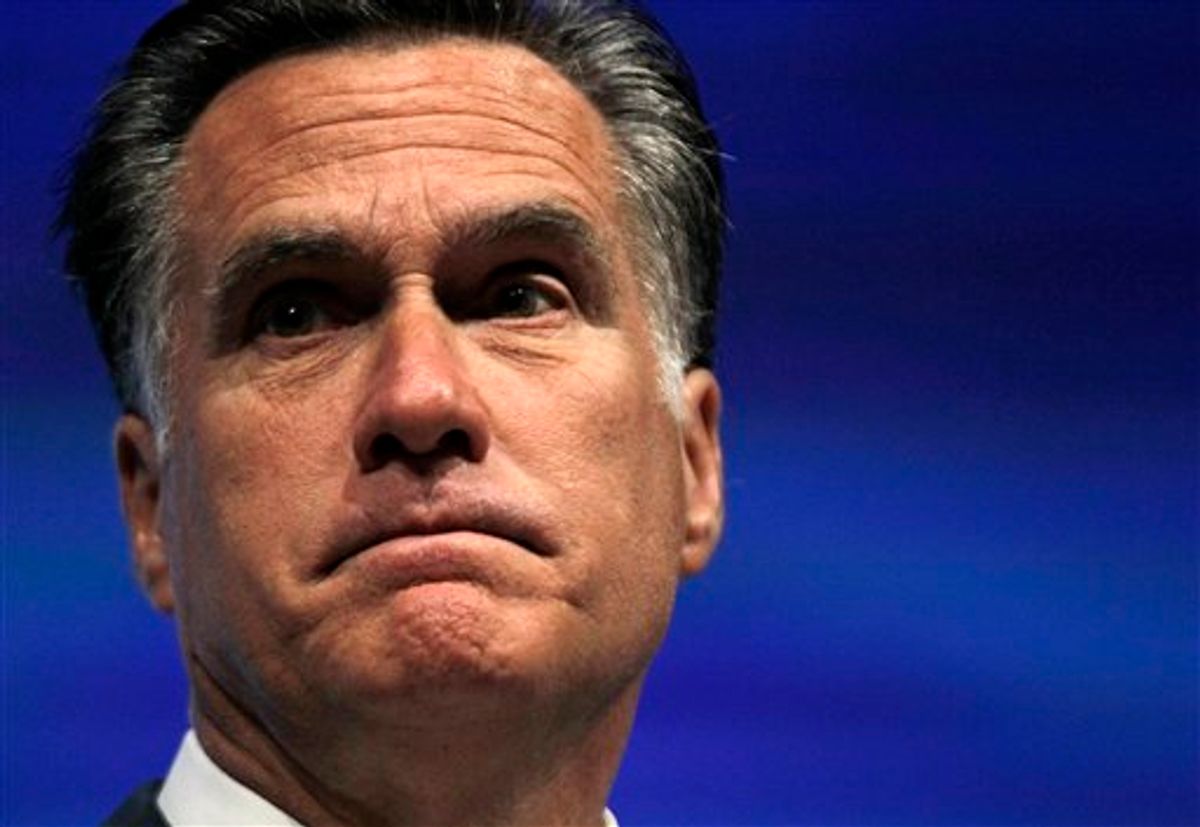

Blessed with parodically presidential good looks, yet cursed with the unconvincing mannerisms of an early-generation android without its update patch, Romney is that most discombobulating of political phenomena—a boring enigma. Trying to figure out his true nature is akin to facing a block of polystyrene. You can’t see inside, and you can’t get a toehold. You’re left with analogies. Romney has been dubbed the next Herbert Hoover, awarded the honorary George H.W. Bush “Wimp” prize from Newsweek, and compared to a porn-movie queen because he changes his positions so often (this last from Arlen Specter, who only changes parties). Those of a more artistic bent have dubbed Romney a latter-day Zelig or, more arcanely, the Man without Qualities, although this is an insult to Robert Musil’s fictional hero, who may have shared Romney’s unwillingness to take a firm position on anything but at least had the courtesy not to seek political power.

Blessed with parodically presidential good looks, yet cursed with the unconvincing mannerisms of an early-generation android without its update patch, Romney is that most discombobulating of political phenomena—a boring enigma. Trying to figure out his true nature is akin to facing a block of polystyrene. You can’t see inside, and you can’t get a toehold. You’re left with analogies. Romney has been dubbed the next Herbert Hoover, awarded the honorary George H.W. Bush “Wimp” prize from Newsweek, and compared to a porn-movie queen because he changes his positions so often (this last from Arlen Specter, who only changes parties). Those of a more artistic bent have dubbed Romney a latter-day Zelig or, more arcanely, the Man without Qualities, although this is an insult to Robert Musil’s fictional hero, who may have shared Romney’s unwillingness to take a firm position on anything but at least had the courtesy not to seek political power.

The paradox of Romney is that even as he wants to run the world, he’s busy running away from its gaze. Although neither a dope like Dan Quayle nor an ignoramus like Sarah Palin—he has read Guns, Germs, and Steel even if he didn’t quite understand it—he has waged a campaign most memorable for its absence of specific ideas. While implying that President Barack Obama is somehow not a real American—for a phantasm to win he must turn his opponent into one, too—Romney basically asks voters to trust in his economic acumen and his leadership. But how can you lead when nobody can find you? He hides from his religion, his political achievements, his big scores at Bain Capital, his tax records, his old public utterances, his new public utterances—hides from everything that might not appeal to whatever voters he happens to be wooing at that particular moment. “Forget about yesterday,” he seems to be saying, “What matters is who I say I am right now.”

A great many empty suits have run for president, but seldom has one been so willing to flaunt his own lack of vision. Indeed, he’s the only nominee I can remember who, in choosing his running mate, was hoping to gain substance. There is, of course, nothing strange about a candidate pretending to be somebody else, but when Richard Nixon unveiled the “New Nixon” in 1968, you knew who he was pretending not to be. With Mitt, you suspect even Romney himself doesn’t know. He’s something new in American politics, if not American culture: a potential president so weightless that he makes Charles Foster Kane look as grounded as Dwight Eisenhower. At least you could tell what that mogul yearned for deep down inside, even if it was only that stupid sled.

While it would be invidious to suggest that Romney has no inner life (a quality that, to be fair, worked wonders for Ronald Reagan), even veteran Mittologists aren’t quite sure what goes on behind the synthetic smile. But they start with the Oedipal. As the worshipful son of a successful businessman whose “brainwashing” gaffe put the kibosh on his presidential hopes, Romney couldn’t fail to learn lessons from his father’s political failures, although he picked up the wrong ones. Tossing overboard what was admirable in George Romney’s legacy—his principled stands within the GOP on issues like civil rights—Mitt became so cautious that even his sister says that he uses vagueness as camouflage. But as the great Sigmund would remind us, an obsession with bottling up what you think will always produce its own elaborate symptomology. Romney rarely speaks off the cuff without landing in trouble. Even more than Joe Biden, who’s Metternich by comparison, he’s a walking gaffe-o-matic, which may be the most likably authentic thing about him.

The most unlikably inauthentic is his way of shifting positions to win favor, then acting shocked, even offended, when it’s suggested he’s done so. It’s tempting to write this off as sheer opportunism, and to be sure, shamelessness is no small part of his M.O.—just think about that trip to Israel with Sheldon Adelson. Yet watching Romney in action, I’m struck that he can’t understand why everyone seems to fixate on his constantly shifting positions. Such puzzlement may finally point us to one of the keys to his character. Unlike most of us who care about politics, Romney thinks of policies and ideologies as being external, contingent. In his mind, what he says and does are distinct from who he is.

In this, he’s a true child of the automobile industry. Romney grew up knowing that what ultimately mattered in Detroit wasn’t any model’s ever-changing features—swooping fins, good gas mileage, nifty little side portholes—but whether the public wanted them enough to buy the car that year. Far from representing some enduring value to be fought for, these features were conditional and evanescent—they changed in accordance with shifting tastes. If the public wanted big grilles, you gave them big grilles; if they wanted power windows, you installed push buttons. The only unchanging consideration was the popularity of the brand. The models themselves didn’t matter as long as a Cadillac was always a Cadillac—and made money.

Romney has pursued his political career in the same bottom-line spirit. He approaches every election like someone rolling out that fall’s cars. When running for office in Massachusetts, he brought out a sporty model that was gay-friendly and rather liberal; pushing for the Republican nomination after the dire Bush years, he played the luxury sedan; trying to get votes from Tea Party types, he has dressed himself up as a Hummer and chosen as his veep a zealot who used to give staffers copies of Atlas Shrugged for Christmas. For Romney, Paul Ryan’s only an accessory, like optional four-wheel drive, designed to close the sale with the party faithful. What matters is triumph of the brand itself, The Romney.

If Romney’s view of life has any principled underpinning, it comes from his faith, but on the campaign trail, Mormonism has turned into the religion that dare not speak its name. His campaign staff always treats it as un-American bigotry when somebody points out that a presidential hopeful’s ultimate concern (as the mid-century theologian Paul Tillich called religion) is not wholly irrelevant to his candidacy, especially when, like Romney, he’s deeply embedded in his church’s institutions and power structure. Yet, in fact, it’s the candidate’s own fear of bringing up the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-Day Saints that intensifies the old perception that it is a cultish outlaw religion.

A bolder candidate would embrace the achievements of the Mormon Church and its culture. An authentically homegrown American religion, it’s steeped in this nation’s founding values, from the celebration of honesty, hard work, and financial prosperity to a rich sense of family and community—all held together by a domineering patriarchy. Deeply and, for some, oppressively conservative, it offers a vision of life that millions of Americans might well find appealing. Romney has made the calculated choice not to do this. In keeping his faith largely under wraps, he reflects the identity crisis of Mormonism. Like his church, Romney is at once desperate for mainstream acceptance (he yearns, after all, to be president) yet equally desperate to make sure that we don’t know too much, that we’re kept outside.

Small wonder that, out on the stump, Romney often seems uncomfortable in his own carefully tended skin. There’s just so much he’s reluctant to talk about, even the worthwhile things he’s done along the way. Before the Salt Lake City Olympics, for instance, he persuaded local organizers to set aside their hostility to homosexuality and approve an anti-discrimination employment clause for gays and lesbians. Yet what’s disquieting is that, all these years later, you can’t be sure what led him to do it. Was he trying to avoid an international scandal that might hurt the Salt Lake games? Could he have been trying to protect Mormonism from seeming bigoted and provincial? Did he think it would help him when he ran for governor in Massachusetts later that year? Or was it possible he just thought it the right thing to do? As with so many things about Romney, we just don’t know, and he’s not talking about it now.

The one unwavering constant of Mitt Romney’s life has been the pursuit of success. He wanted to make oodles of money (if he has a Rosebud, we know it’s green) and ascend to the most powerful office in the land, which he’s one unnerving election away from doing. There is, of course, nothing wrong—or inherently Republican—about such grandiose ambitions. Bill Clinton chased those very same goals, albeit in reverse order (which may actually be less admirable). Yet what makes Romney so depressing is that he embodies everything hollow and joyless about the great American dream of success. He’s gotten astonishingly rich without ever showing the pleasure in his good fortune that made this country swoon for FDR and JFK and Ronald Reagan—heck, he even pretended not to care about his wife’s dressage horse in the Olympics. Even worse, he unstintingly seeks power but conveys no abiding awareness that he could use his success for the greater good. Say what you will about Reagan and Clinton, George W. and Barack, these men know what it means to dream of greatness—they wanted to make history. Romney? He just wants to get ahead.

Despite all his weaknesses—his lack of ideas, his low “likability” ratings, his maladroit campaigning—Romney just may get elected. Which will bring us back to the same spooky question: Who is Mitt Romney?

At best, he will morph back into what his early champions claimed he is—a smart, temperamentally conservative CEO who casts himself in the role of a nonideological problem-solver. This is not impossible. After all, Romney possesses the sense of entitlement, not to mention the vanity, of a successful businessman who, accustomed to being boss, isn’t about to let those Tea Party twerps push him around one second longer. It’s delightful to imagine self-serious Vice President Ryan being sent on fact-finding missions to Moldova and Guinea-Bissau. In this happy scenario, President Romney will try to reclaim some of the political center in search of the next marker of personal success—re-election.

Shares