"The case has been disastrous for almost everyone who touched it. It's like a third rail." So says Harvey Silverglate, an appellate attorney for Jeffrey MacDonald, who has been imprisoned for 33 years for the murders of his wife and two young daughters in 1970. The person Silvergate says this to is Errol Morris, the maker of several seminal documentary films, most notably "The Thin Blue Line," which helped exonerate a man who had been wrongly convicted of killing a police officer in Texas. By the time Silvergate explains his own decision to back away from the case emotionally, it's too late for Morris. He's like a dog with a bone.

The MacDonald case is an object of obsession for many, with fervent advocates for both sides. Some believe with all their hearts that MacDonald is guilty. Others believe with equal vehemence that he's not. By the end of his new book, "A Wilderness of Errors: The Trials of Jeffrey MacDonald," Morris is careful to state that he does not know whether MacDonald is the killer. He is convinced, however, that MacDonald was "railroaded," that authorities decided early on that he was guilty and that they ignored and concealed physical evidence supporting his account of what happened in the early morning hours of Feb. 17, 1970, in Fort Bragg, N.C. By the end of this highly detailed but consistently engaging book, I was, too.

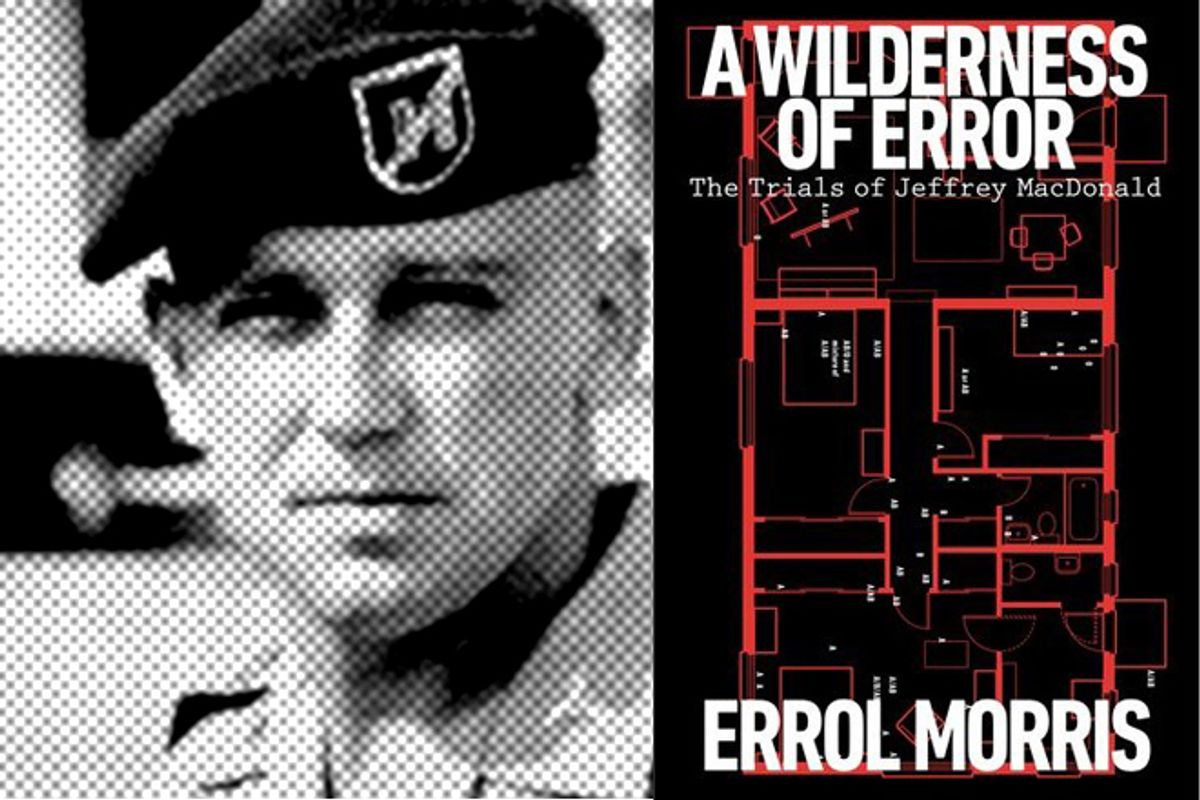

The case was a front-page sensation and often referred to as the Green Beret Murders because MacDonald was group surgeon for the 6th Special Forces Group. It became the subject of a bestselling 1983 book, "Fatal Vision" by Joe McGinniss, which in turn became a widely viewed TV movie. Then New Yorker writer Janet Malcolm took McGinniss' relationship with MacDonald as the subject of "The Journalist and the Murderer," a famous book-length rumination on the duplicity and opportunism of journalism.

MacDonald's experience invokes a couple of Morris' favorite themes. Like "The Thin Blue Line," it illustrates the seductive power of narrative. The crime was initially investigated by the military police at Fort Bragg, and once they decided that MacDonald was the perpetrator, they made virtually no effort to investigate evidence supporting his version of events. It all began when MacDonald called the MPs to his home at 3:42 a.m., where they found MacDonald with stab wounds, abrasions and a collapsed lung. His wife, Colette, lying in the bedroom, had been brutally beaten and stabbed many times with two different weapons. Their 2- and 5-year-old daughters, also stabbed to death, were in their beds.

MacDonald claimed that he has been sleeping on the living room sofa because his half of the marital bed had been wet by one of his daughters. He woke up to find four intruders at his feet, three men and a woman. Two of them assaulted him. After a struggle, he lost consciousness for a while. He came to in the hallway and called the police. The intruders, he said, looked like hippies. The woman had long blond hair, a floppy hat and boots, and was carrying a candle. They were, he claimed, chanting "Kill the pigs. Acid's groovy."

As outlandish as MacDonald's account sounds today, it seemed plausible at the time, less than a year after followers of Charles Manson had committed the Tate-LaBianca murders in Los Angeles. (A copy of Esquire magazine containing a sensationalistic account of those killings and other purportedly satanic activities among Southern California hippies was found in MacDonald's living room.) However, with the passing years, this scenario came to sound more and more like a preposterous cover story.

Nevertheless, as Morris details, there was evidence supporting MacDonald's version of events. An MP responding to the call saw a woman matching the description of one of the attackers (long, light-colored hair, floppy hat, boots) standing on a nearby street corner. A narcotics detective for the local police had an informant, Helena Stoeckley, who sometimes wore a long blond wig, floppy hat and boots, and he had seen her get into a car with three men several hours before the murders. He sought out Stoeckley the next day and alerted the MPs that she was available for questioning, but no one was sent to interview her or examine her belongings. Stoeckley later destroyed her wig and hat, and until her death in 1983, she would often talk of being present during the murders, although when called upon to testify to this in court in 1979, she denied it.

MacDonald was the most logical suspect for the crime, but he had no discernible motive and no history of violent behavior or mental illness. As a result, the case against him -- first examined in a military hearing -- relied entirely on physical evidence. However, the crime scene had been hopelessly contaminated by inexperienced MPs and incompetent investigators. Key pieces of evidence were moved, lost, destroyed, mislabeled, stolen, overlooked or simply uncollected.

For these reasons, the initial army evaluation of the charges against MacDonald declared them to be "not true." MacDonald's father-in-law, at first a vocal champion of his innocence, became enraged with MacDonald for refusing to help him hunt down the killers, making an ill-advised appearance on a TV talk show and moving to California. The father-in-law did a 180-degree turn, deciding that MacDonald must be the culprit, and from that point he advocated tirelessly for a federal trial. He succeeded in 1979. (The FBI refused to pursue the case for several years because the MPs had made such a botch of it.) This was the trial that McGinniss covered and in which MacDonald was convicted. Decades of appeals followed, including a forthcoming request for a retrial to consider evidence uncovered in the years since.

"A Wilderness of Errors" mostly consists of detailed reexaminations of the evidence and the trial, as well as of the unfolding saga of the defense's efforts to establish Stoeckley's role in the crime. The judge, Morris argues persuasively, was blatantly biased against MacDonald and his abrasive lawyer. The prosecution, aware of how tenuous their case was, staged impressive but nonsensical reenactments and hired a psychiatrist whose specialty was declaring defendants to be psychopaths.

This pushes another of Morris' buttons: a similar celebrity shrink, James "Dr. Death" Grigson, supplied the same diagnosis for Randall Dale Adams, the innocent man sentenced to death in "The Thin Blue Line." According to the highly dubious rationale used by such doctors, the less crazy a suspect appears, the more likely he is to be a psychopath, because being able to convincingly feign sanity is a sign of the psychopathology. In a similar tautology, MacDonald's alleged psychopathy explains why he committed the crime but the only real evidence that he's a psychopath is the "fact" that he committed the crime.

As Morris sees it, McGinniss, although at first presenting himself as favoring MacDonald's side, eventually subscribed to the prosecution's version of events because it made for a better, more marketable book. Malcolm, while raising interesting questions, meandered in philosophical contemplation of the unresolvable nature of truth, losing touch with the fact that three people really were murdered and that somebody really was serving three consecutive life sentences for the crime. Morris grows most exasperated when Malcolm surveys the "huge packages" of evidence MacDonald sent to her and decides not to read them, because "I cannot learn anything about MacDonald's guilt or innocence from this material." Morris counters, "The only way you can learn anything about MacDonald's guilt or innocence is from this mountain of documents. True, evidence never speaks for itself. It exists as part of a theory or story or narrative, but stories can be tested against reality."

McGinniss' book and the film based on it have effectively swamped any alternate stories in the public mind, but Morris keeps coming back to that evidence. He's not the writer Malcolm is, but damned if he's not dogged. "A Wilderness of Error" is a beautifully produced book, with chapters set off by line drawings of crucial objects in the case: a toppled coffee table, a flower pot, a rocking horse. It's reminiscent of the recurring images in "The Thin Blue Line," iconic and mysterious, always on the verge of revealing the secrets they stand for but never quite yielding them. Morris may geek out on minutiae and hypotheticals, but he is enough of an artist to convey that every crime scene is a dialogue between time, as it sweeps away the irrecoverable past, and the material world.

Art and justice are not the same thing, however, and every would-be Encyclopedia Brown poring over "A Wilderness of Error" will find something special to fixate on or be appalled by: the prosecution's attempts to suppress Stoeckley's testimony and their flagrant disrespect for the principle of discovery are just two. Other readers, profoundly wedded to the belief that MacDonald is guilty, will refuse to reconsider. Jeffrey MacDonald's version of what happened on Feb. 17, 1970, is pretty hard to credit, but it is not impossible. By the end of "A Wilderness of Error" it's difficult to be sure of anything besides whether or not he got a fair trial. He didn't.

Shares