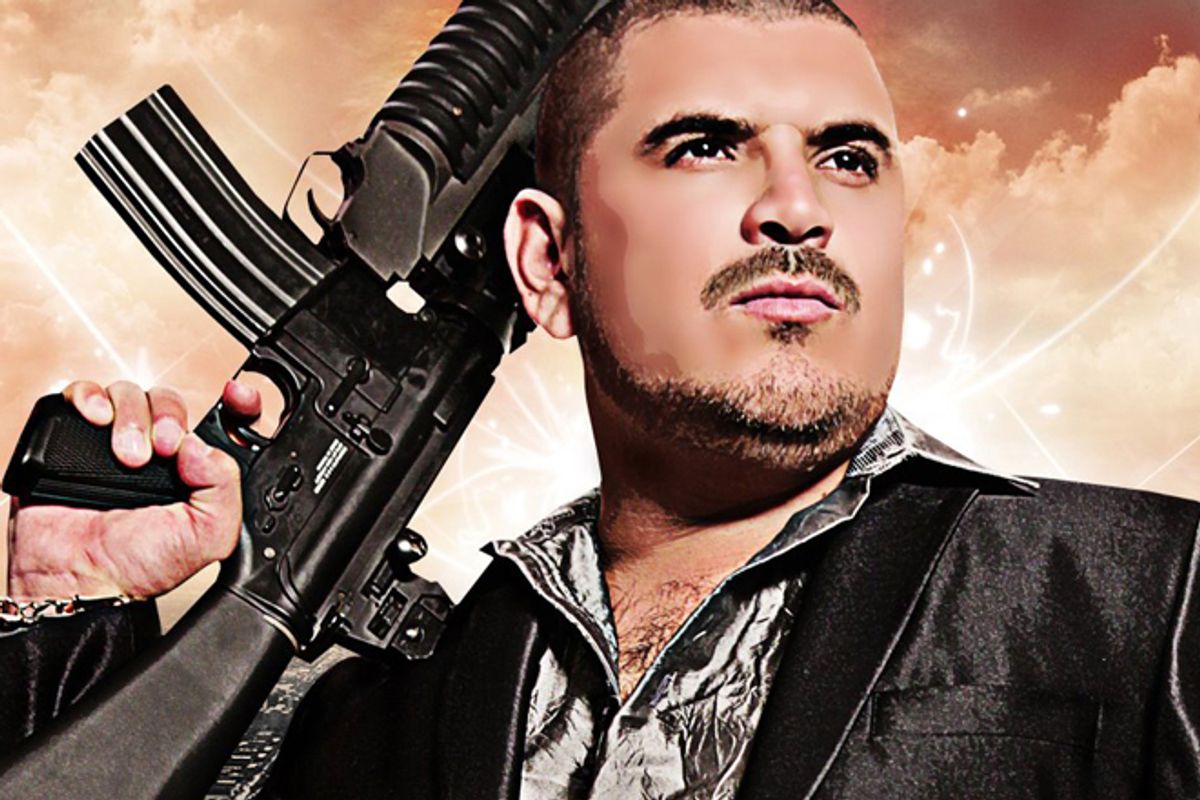

It’s 2 a.m. when El Komander, the bestselling balladeer of cartel life and death, takes the stage at Club El Rodeo in Mexicali, Mexico, a maquiladora boomtown just across the border from sleepy Calexico, Calif. Buzz-cut, goateed and dressed in an all-black costume of oversize tinted shades, crisp parachute pants and polished knee and elbow guards, he opens his set with his tuba- and accordion-driven hit, “The Devil’s Advocate”:

Born in Sinaloa

Where killing is learned

I bear the blood of combat

And orders to execute

The verse draws raucous cheers from the capacity-plus crowd, which I’m told is thick with members of the Sinaloa Cartel, the most powerful drug trafficking syndicate in the world. I’m still scanning the scene for signs of this when Komander points a black-gloved index finger at the VIP mezzanine and sends a shout-out to his hometown of Culiacan, the Pacific coastal city where the cartel is based. A dozen VIPs, a couple wearing sunglasses, solemnly raise their glasses in recognition. On the club floor, Komander’s gesture sends the 20- and 30-somethings into frenzy. These are his die-hard fans, mostly young and middle class, who have made El Komander (real name Alfredo Rios) the very wealthy face and voice of the trans-border narco-culture phenomenon called "el movimiento alterado."

Komander is a multimedia narco icon, working across the music, film and fashion industries that make up this “movement,” which produces commodified, glammed-up spins on the Mexican narcocorrido — drug ballads that go back a century but produced its first pop stars in the early 1980s. It was Komander’s earliest videos dating to 2009 that first showcased the alterado scene’s emblematic fashion statements: ballistic vests stitched with Gucci and Burberry fabrics, blinged-out rosaries and crosses, sartorial baselines of commando-raid Kevlar black. Several El Rodeo clubbers wear these or their candy-colored variants. One kid sports a T-shirt featuring a hauntingly beautiful depiction of a stitch-lipped Santa Muerte, the female Saint of Death, around whom a Catholic cult has grown in tandem with Mexico’s body count.

Komander ends his set a little after 4 a.m. with his anthem, “Mafia Nueva,” where he references the trappings of lo narco (the cartel life): Buchannan’s Scotch, Cheyenne trucks and cuernos, or “horns” — slang for AK-47s. He emerges an hour later from the club’s back door, still in sunglasses and surrounded by guards, and works his way through throngs of screaming female fans gathered in the club’s parking lot toward an idling, burnt-orange Ford pickup truck with his AK-47-themed logo emblazoned on the cab. As dawn cracks, Komander, his manager and a guard roll out sandwiched by black bulletproof Hummers.

The Hummers are no theatrical touch, but a necessary precaution. The original narcocorrido icon Chalino Sanchez suffered his first gunshot wound during a show not far from here in 1992, following a concert in the Coachella Valley. A few months later, his bullet-ridden corpse turned up roadside in Culiacan. In recent years, the dangers faced by narcocorridistas have grown along with the complexity and brutality of drug war politics, not to mention the size and lethality of the weapons employed by the state, the cartels and the groups in between. Dozens of musicians have been shot, killed or tortured since 2006, caught up in the national tragedy that is their inspiration.

While violence has been part of corrido culture since the '90s, old rural-style stars like Sanchez wouldn’t recognize much of themselves in the new scene. "Alterado" translates as “altered,” as in agitated. Connotations include buzzed, sickly and demented. In gringo terms, it’s narco-core. Until the mid-2000s, narcocorridistas dressed in a hick ranchero style — cowboy hats, tassel-vests and ostrich boots. They played small clubs and restaurants with tables pushed into corners. If they carried, they packed a six-shooter into their belts or between the seats of a rusty pickup. Alterado stars shop Versace, fill Mexican soccer stadiums, and trot bazookas onstage. On the U.S. side of the border, they tour a growing circuit including the House of Blues and L.A.’s Nokia Theater. They make gruesome narco films like Komander’s "The Executor," full of severed heads and buzz-saw torture sessions. They pull down $50,000 for weekend club gigs. Like the Sinaloa Cartel, their brand is global.

In 1999, the cultural critic Sam Quinones described the Sanchez-inspired California corrido boom as “the Sinaloaization of L.A. Mexican culture.” Acts like Komander have turned that formulation on its head. El movimiento alterado is the brainchild of twin immigrant impresarios Omar and Adolfo Valenzuela, whose L.A.-based company, Los Twiins Enterprises, has repackaged the narcocorrido for re-export. Not far from a Warner Bros. studio lot, their narco-‘sploitation laboratory produces stylized reflections of Mexico’s drug war for shipment across the U.S. and Mexico by the million, return address: Burbank.

* *

The San Fernando Valley is where show business goes to be left alone. In the Valley there is no Grauman’s Chinese Theater. Few studios offer tours. Within a maze of tidy suburban lawns the porn industry achieves invisibility. And on a sleepy stretch of South Burbank Boulevard, you’ll need luck finding the sign-less green storefront with black tinted windows that is the deceptively humble home of Los Twiins Enterprises.

It was here that over the summer I met Adolfo Valenzuela to discuss the business he runs with his 36-year-old twin brother, Omar. I entered expecting to find at least some trace of the menace infusing Los Twiins’ blood-drenched narco-films and cartel party anthems (“Blowing up heads/ we’re bloodthirsty, crazy/ very spaced out/ we love to kill”). Instead I’m greeted by a row of giggling teenagers, Valenzuela nephews and nieces, who run the Twiins' sophisticated social media operation. They upload videos and narco-film trailers on YouTube and Facebook, bypassing Mexican radio and television bans and feeding a growing international fan base.

“It’s crazy, we’re getting mail and orders from Latin America, Amsterdam, Germany, everywhere,” says the soft-spoken Valenzuela in his soundproof recording studio. “Alterado has gone global and we’re only getting started. A lot of people are angry about our success, which has been revolutionary. Older musicians, Mexican politicians, the media, they don’t like it. They say that it glorifies the violence, but it just reflects reality, and were not forcing anyone to buy it.”

The Spanish-language music market in America is 35 million strong, more than half of which consumes the genre known as Mexican Regional, which includes corrido acts like El Komander. Much of the Valenzuelas’ success is underground and online, so numbers are hard to nail down. But the CDs, downloads and page views are often measured in seven digits. The video for Komander’s party song “Drunken and Scandalous” has been viewed more than 3 million times on YouTube. On the day of my visit, Adolfo was busy finalizing distribution deals with iTunes and Wal-Mart.

The product of a middle-class musician family, Adolfo and Omar emigrated from Culiacan to East L.A. at 16 and found a home in the high school jazz band. They won music scholarships to the University of Southern California and Cal State, Los Angeles, respectively, and while studying did session work playing drums and horns behind marquee names like Tito Puente. After graduation, capitalist dreams drew them to the other side of the studio glass. In 1997, still just 19 years old, they founded Los Twiins Enterprises. As producers they fast earned reputations as cunning connoisseurs of the crossover. They developed artists like Panama’s El General and Mexico’s Banda El Recodo, always attuned to the commercial possibilities of the moment. When the New York Times profiled them in 2006, they were busy producing socially conscious immigrant-rights anthems and talking up the prospects for their Spanish-language version of the Star-Spangled Banner. Adolfo was especially proud of a multi-artist song he described as the “Mexican-American ‘We Are the World.’”

Months after the twins’ close-up in the Times came the catastrophe that would prove, perversely, to be the twins’ biggest stroke of business luck, one that would set them on a blood-splattered trajectory to make their immigrant rights anthems look like the innocent period gimmicks they were. On Dec. 11, 2006, Mexican President Felipe Calderon sent 6,500 federal troops to contain a rising tide of drug-related violence in the southern state of Michoacan. It was the first salvo in Mexico’s “war on drugs.” Within a year, a ceaseless torrent of shootings, beheadings, kidnappings and reprisals transformed front-line border towns into war zones. The aftershocks affected every aspect of Mexican life. The narcocultura was born.

“Writers are barometers, and suddenly they were talking about the drug war, the cartels, the sicarios [assassins],” says Omar Venezuela, who runs the Mexican side of the Twiins’ operation from his home in Culiacan. The fashion around the music also shifted. In corrido clubs like El Rodeo in East L.A. (where Michael Mann’s "Collateral" was partly shot), the ranchero look gave way to Dolce and Gabbana flash. The new styles mirrored the threads on the backs of arrested cartel bigs, whose choreographed perp-walks had effectively become trend-setting red carpet events. “The corrido clubs in Mexico and L.A. started looking more like Hollywood clubs, with drug war touches, like images of guns and grenades,” says Omar.

The Twiins saw the opening and began angling to get ahead of the shift. What they needed was a star. Then one spring afternoon in 2008 Omar’s cousin told him about a shy 20-year-old from Culiacan who worked in his downtown L.A. clothing shop, a good-looking kid who wrote corridos and wanted to break into the industry. Omar agreed to meet with him, and that night pulled into his driveway to find Alfredo Rios waiting in front of his house holding a battered acoustic guitar. He introduced himself and began to sing one of his originals. Midway through the song, Omar stopped him and told him to quit his day job.

“I only needed a minute to know he was the future,” says Omar. “He sang about the narco lifestyle in a fresh way. The brands, the cars, the weapons, the parties. I’d never heard Armani name-dropped in a corrido before.”

Komander’s reboot of the corrido was all the twins needed. He had modernized the Mexican outlaw ballad with gangsta rap and Mexicanized "Scarface" aesthetics to reflect 21st-century cartel life. The Twiins christened Rios “El Komander,” designed a logo formed of golden AK-47s and a 9mm pistol, and produced his first single, “El Katch” (Mexican-accented “Cash”), together with a video, in which Komander sings about cars and kush against a background of AK's and ass. They flooded club parking lots with free CDs and posted links to the video on popular blogs. Then they waited for the echo. It came back louder than they had any right to hope. Within weeks, “El Katch” was scorching YouTube and broke into Billboard’s Mexican Regional chart.

With Komander established, the Valenzuelas began producing other acts in the Komander mold, chief among them Los BuKanas de Culiacan, Los Buchones, Los 2 Priimos, and Los Edicion de Culiacan. Among the twins’ early and influential acts was Los BuKanas, whose “Los Sanguinarios del M1” (“The Bloodthirsty Killers of M1”) is an alterado classic. The song, released in early 2010, is an ode to Manuel Torres Felix, a notorious sadist nicknamed “Ondeado” (“The Crazy One”) who handles security for the Sinaloa Cartel. The song boasts nearly 20 million views on YouTube and its story forms the basis of the Twiins-produced narco-film of the same name.

“People right now want to hear about grenades, AK-47s, bazookas,” says Los BuKanas bandleader Jaime Carrillo, a veteran musician who decades ago played with Salino Sanchez. “We sing about high-tech weapons because it’s in demand. It’s the reality of right now. If we were playing old-school corridos, we’d barely gig.”

This understanding of corridos as contemporary news reports — a Mexican version of Chuck D’s description of rap as black America’s CNN — goes back to the days of Porfirio Diaz. Proto-corridos even functioned as musical war reportage during the Mexican War for Independence. They later developed during Prohibition into a form of border blues narrating the trials and tribulations of migrants, hustlers, bootleggers and traffickers. “Corrido is like rap, you need street flavor,” Adolfo explains. “But it’s nothing new. Ballads about outlaws have been in the Mexican culture since Pancho Villa.”

Pancho Villa comes up a lot in discussions of the new corrido culture. Like today’s cartel leaders, the bandolier-wearing revolutionary war hero came from peasant stock in a land of massive inherited wealth controlled by a corrupt oligarchic elite. Insofar as the cartels are against Mexico’s contemporary corrupt establishment elite, they are accepted into this tradition. Robin Hoods with buzz saws, machine guns and power drills. “In Mexico, many view the cartels as underdog characters — like American narratives about self-made men,” says Juan Carlos Ramirez-Pimienta, professor of border studies at San Diego State University. “For the Mexican-American audience, alterado is also cathartic. The community feels under siege, especially undocumented workers who live in constant fear of getting deported. So songs about powerful Mexicans can be intoxicating.”

And not just for the poor and dispossessed.

“I keep meeting third-generation middle-class Chicano kids who grew up speaking English and listening to rap but who are now learning Spanish through the new narcocorridos,” says Brian Plascencia, the veteran manager of L.A. corrido group Los Nueves Rebeldes. “It’s not the negative influence some say it is. The narcocorridistas are the same as the gangsta rappers — ‘Fake it til you make it’. Do some artists occasionally hang out with mafia? So did Frank Sinatra.”

* *

Listening to the Twiins place massive bets on the future — their email signature is “Taking Over The Music Industry!!!!” — it’s almost possible to forget that they’re talking about torture-filled polka party jams about Mexican cartel politics and the underdog heroics of hired killers. The music is banned from Mexican radio, and there is a movement in Mexican parliament to ban live performances. “I understand the critics’ viewpoint,” says Omar, “but right now young people want this, and what they want is my business. The demand will be there until the violence stops. Then we’ll sell something else.”

There are serious cultural obstacles to mainstreaming alterado in the U.S. These were manifest in the reality series about the Twiins, "Los Twins," that ran in 2011 on the Spanish-language cable channel Mun2. (Tag line: “Producing the American Dream, one track at a time.”) In one episode, worlds collide with unintentional comedy when DJ Paul and Juicy J of hip-hop act Three 6 Mafia join the Twiins in the studio to explore the scope of a possible collaboration. (That scope turns out to be extremely narrow.) But, in a later episode, a meeting with Snoop Dogg (“Alterado?” he says. “I like the way that sounds.”) winds up leading to a studio collaboration with Cypress Hill, and the Twiins continue to take inspiration from drug-tinged genres that began on the margins and grew to conquer the world.

“Reggaeton and hip-hop also went in a mafia direction,” says Adolfo. “Even rock was criticized in the beginning. It’s what we have to take. Our idea is to start mixing in English songs and American artists. The evolution will take a few years, but if it works, we’ll change history again.”

Omar Valenzuela admits to sometimes seeking the blessing of cartel dons before releasing songs. And there’s no denying that Twiins-produced songs like “United Carteles” function as statements of allegiance to specific cartels, as well as implicit threats against others, such as the Juarez and Beltran Leyva cartels. But the twins and their musicians deny direct financial and social ties to the cartels. The result is a wire act: They sing about certain cartel figures with warm familiarity, yet maintain a safe distance in reality. It’s a line that some alterado groups tread more gingerly than others. “We’re extremely careful about what we write,” says David Guzman, the 21-year-old leader of Ondeado, a Twiins alterado act. “We never mention names or play cartel parties. We try to keep our heads down while making music about what’s happening in Mexico.”

No Twiins artists have yet been killed or kidnapped on the road, but there was one close call. Last year, unknown gunmen ambushed the convoy of Gerardo Ortiz, formerly of Los Twiins and now with the rival Del Records. (The labels compete enough to beg comparisons with Death Row and Bad Boy.) The attackers killed two in the convoy, but Ortiz, whose symbol is a golden grenade, survived to take six trophies at the 2011 Billboard Mexican Music Awards.

For his part, El Komander tries his best not to think about death by bullets. “There are places in Mexico that are very dangerous, and sometimes you worry, but the only thing you can do is leave it up to God and just go to work,” he says. “In 80 percent of my songs I avoid referring to specific cartels or individuals because I don’t like it and it’s not necessary to make good music. I have never received a threat, but sadly in this profession violence can happen. In Mexico we are all exposed.”

In the U.S., not so much. Most L.A.-based narcocorridistas lead normal lives in middle-class suburban hamlets that remind one more of El Brady Bunch than El Chapo. The day after the Komander show in Mexicali, I drove back to L.A. to meet with Jaime Carrillo, the veteran corrido musician who leads Los BuKanas. Carrillo lives with his family on a leafy street in Huntington Park. When I arrive, his entrepreneurial wife is at the kitchen table, building binged-out rosaries and jewel-encrusted Ed Hardy shirts, some of which bear the visage of Jesus Malverde, the patron saint of drug dealers and a corrido icon known as the “angel of the poor.”

We walk out to his attached garage, where Carrillo keeps a makeshift office amid stacks of musical equipment. On the walls are years of posters for Los BuKanas concerts and Los Twiins showcase events. One of these, from a 2010 show at L.A.’s Nokia Theater, shows a boombox with six-barreled Gatling-style rotary cannons sticking out from the speakers. I’m admiring the poster when Carrillo pulls out a large case that looks like it might hold a trombone. He unclasps it to reveal something else: a decommissioned Army-issued bazooka he bought at a Denver gun show. “We use the bazooka to pump the crowd,” he says, hoisting the massive weapon onto a brawny shoulder. “We bring it out at the end as part of the finale. Audiences go wild for it.”

Carrillo is a massive, intimidating presence even without a bazooka in his hands. With the weapon, he looks like a stock villain from "Invasion U.S.A." -- a composite of Middle America’s worst post-9/11 nightmares. I tell him this and and he laughs. “Yeah, sometimes it’s a pain to bring through airports,” he admits. “We get hassled by security or whatever, but we have all the paperwork for it.”

Carrillo is not blind to the absurdity of play-acting onstage with a bazooka. “Times change,” he says with a shrug. “I sang party songs when people used to want party songs. Now they want to hear about grenades and ‘goat horns,’ and the style is bulletproof vests. People want to feel like El Chapo.” During his years working the corrido circuit, he’s seen murders in clubs and dealt with his share of gangsters. But these days his exposure to the cartels is minimal and mostly secondhand. “A lot of mafia dudes go to El Rodeo in L.A. and kick back in the VIP,” he says. “If you just come and do your thing, they won’t mess with you.”

When I ask Carrillo how he gets material for his songs, he points to a desktop computer in the corner. There’s this website, blogdelnarco.com, he explains. He visits it three times a day.

Shares